Philadelphia Inquirer - July 25, 1980

Handwriting on the wall: Time to put up or shut up

By Frank Dolson, Sports Editor

For the Phillies, it is time to put up or shut up, time to win some ball games, identify themselves as legitimate pennant contenders... or get broken up by a front office that has treated them with tender, loving, almost paternal care.

The great promise of the 70s, the exhilaration over those three straight division titles, the expectation of the first World Series in Philadelphia in three decades is behind us now. The young, ambitious Phillies of the 70s have matured into the older, seemingly much-less-ambitious Phillies of the '80s. Unless they show signs of life in the two-week, 13-game home stand that begins tonight, unless they demonstrate by their performance, not by their words that they are as hungry for a National League pennant as their long-suffering fans, the team that never quite got over the hump in the 70s will be ready for the junk heap in the '80s.

If their play of the last two years – under easy-going Danny Ozark in 79 and tough-talking Dallas Green in '80 – is any indication, the front office has miscalculated by refusing to break up a club that was already crumbling. The veterans don't like to hear that, but the record speaks for itself. Last year's Phillies were 84-78. This year's Phillies are 47-44. That adds up to a season and a half of mediocrity.

Granted, the pitching has been crippled. The starting rotation has been patchwork. But pitching didn't cause the club's latest skid. Lack of hitting caused that. And lack of defense, supposedly the Phillies' strong suit.

The late, lamented, three-game flop in Cincinnati came as an eye-opener to at least one sharp observer, who hadn't seen the team play in a while. Jim Bunning, who spent five years managing in the Phillies' farm system and now represents several Phillies players, attended the series and came away shaking his head.

"I can't believe it," Bunning said. "I really can't. It's sad. ... I watched them three straight games, and (they looked as if) they could've cared less whether they won or lost. If you will not dive to stop a ball, you do not care whether you win or lose.... The kids are the only ones who are busting their butts. That team is going down the tube. If they don't get well on this home stand, they're gone."

It is Bunning's feeling that the Phillies stood pat too long, that the front office was so sold on the team it built in the early 70s that it failed to make the moves necessary for success in the '80s. That feeling was expressed by the former All-Star pitcher in a letter he wrote to Ruly Carpenter in April of 77. Some, no doubt, will call it sour grapes, since the Phillies had fired Bunning the previous October. But if you know Jim, you . know he says what he thinks, no matter what the circumstances.

"It has been six months since I have left your organization," Dunning wrote, "and some things have continued to haunt me.... You may want to stop reading this letter right now for what is to follow you might not want to hear, but I will continue in case you are interested.

"First, the Phillies are now competitive in the National League and the Triple A level for the first time since the middle '60s, which I believe was a joint effort of many, including some no longer with the organization.... Now some things are beginning to happen which I believe should be brought to your attention, (things that) also happened in the middle '60s, causing five miserable seasons at the major league level. Many strong major league prospects have been traded away in order to win now. True, you did win the Eastern Division, but failed in the playoffs.... 1977 had better be the year of the Phillies or look out. 1965-1970 will be repeated as your depth of players has been depleted. Can you afford to go through five lean years under the present conditions in baseball? I doubt it.... Whether you believe any or all of this letter (Bunning concluded), it will be a matter of history in five years."

The feeling grows that Bunning may have been right, and that it won't even take the full five years to prove it.

By standing pat, even after the '79 disaster, the front office may have stepped up the timetable.

The Phillies have treated their players exceptionally well. A rapport exists between management and players on this team that probably doesn't exist anywhere else. But that very closeness appears to have been counterproductive. Secure players, contented players don't necessarily make winning players.

It is becoming increasingly evident that a change of managers, a switch from good, old, easy-going Danny to hard-talking Dallas isn't the answer. If anything, veteran players seem to be rebelling at the Green approach, rather than buying it. For Dallas, that must be awfully tough to swallow.

Last winter, shortly before heading south, he had first launched into his "we, not I" philosophy, something he has repeatedly hammered away at since. "I think you can see the different personalities that we have down there," he said then. "They're so diverse that I don't think anything really got them together totally.... We've got to tie it all together. We can do that."

Along about then Paul Owens, the team's general manager, nodded and said, "I don't think any of them ever really down deep don't want to win the whole thing for themselves as a team, but I think sometimes someone has to point that out to them, and only the manager can do that. We can't do it from up here. It has to be done down there, and I think Dallas has that knack of being able to do that."

Well, after three-plus months, after 91 games, not even Dallas Green has been able to do it. The atmosphere is surely different, but the mediocrity is the same.

"I'm sure there's a little different feeling around here," Greg Luzinski said the other day. "He (Green) has been playing his boys a little you know, (Keith) Moreland, Lonnie Smith. I don't know if he's trying to push the older guys or what. But there's a definite feeling around here, and he's tried to create it. He's created, I think, a feeling among the team that we can't make mistakes...."

No matter. They've made them, anyway. And if they continue to make them in the upcoming home stand, if they don't win at least eight or nine of those 13 games, they will provide additional evidence that the biggest mistake of all was made by the front office when it refused to see the handwriting on the wall.

Phils home for awhile

The Phillies, coming off a six-game losing streak on the road, hope to find the confines of Veterans Stadium a little more to their liking as they open the longest homestand of the season at 5:35 p.m. today with a twi-night double-header against the Atlanta Braves.

The homestand, which runs through Aug. 7, also includes three-game series with Houston, Cincinnati and St. Louis.

During this last, disastrous road trip the Phils lost three of four to the Braves and were swept in three games by the Reds.

BASEBALL

PHILLIES vs. Atlanta, twi-night doubleheader at Veterans Stadium, 5:35 p.m. (Radlo-KYW-1060)

Phils need better bullpen to make their pitch

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

There are certain things you know you can expect in every baseball season.

Pete Rose will pass Honus Wagner on the all-time singles-with-two-outs-and-a-guy-on-first list or something. Steve Carlton will pitch a one-hitter.

Somebody will get disillusioned with Bobby Bonds. Willie Montanez will flip a bat.

Nolan Ryan will strike out 14 guys and lose. Somebody named Niekro will beat the Phillies. Somebody named Berenyi also will beat the Phillies.

And that isn't all.

You know you can expect losing streaks, too. And there is one simple reason why the Phillies have managed to avoid any before their present six-game skid.

That reason is named Steve Carlton.

It's almost impossible to lose too many games in a row when you have a veritable shutout machine going out every fourth or fifth day and winning practically by himself.

Ten of Carlton's 15 wins this year have come after Phillies losses. He has stopped two three-game losing streaks and five two-game streaks.

Only once has he started a winning streak that was still going when his next turn came around.

Carlton is still pitching better than anybody in his league. But he also is a shade below the killer form he was in from mid-May through mid-June. He needs some help to win now. He has not always gotten it.

The rest of the rotation has not been able to stop this streak, but it is still in decent shape.

Despite his two straight losses, Dick Ruthven has been consistently good for a month. Ditto for Bob Walk. And any team that has three starters it can count on to keep it in games consistently is in better condition than most.

Also, Nino Espinosa has done very well for a guy with no fastball. And even Dan Larson has given up three runs or fewer in three of his five starts. Randy Lerch's problems are almost beyond analysis now.

But one big reason this team has had trouble lately is its bullpen.

Tug McGraw and Warren Brusstar have been working their way back from injuries. Dickie Noles has just one win, two saves and a 7.29 earned-run average since June 17.

Kevin Saucier, whose job has been basically to get one or two hitters in certain situations, has allowed at least one runner (on base when he came in) to score in each of his last four outings.

The last time Ron Reed put together two scoreless appearances in a row was the third week of June.

In this losing streak alone, the bullpen turned one tie game into a five-run deficit, turned a one-run game into a four-run game and turned another one-run deficit into a two-run hole. All the grinding-it-out in the world can't overcome that.

Offensively, the Phillies are always going to have trouble scoring when the guys at the top of the order – Rose and Lonnie Smith – don't get on and Mike Schmidt doesn't crash homers to compensate.

But you know Rose will hit. And while Smith may not be the .410 hitter he was for a while, he isn't the .187 hitter he was on the recent road trip, either.

Schmidt accounted for almost a third of the Phillies' run production the first two months. But Greg Luzinski was hitting behind him then, he didn't have a pulled hamstring and he hadn't gone into his inevitable 2-for-22 streak.

While he might need Luzinski's return to the fifth spot in the batting order to get him back to his earlier neo-Babe Ruth form, you know Schmidt will be better than he looked the last week.

Bake McBride was, simply, the best hitter on the road trip, even on a knee that is getting more tender by the day. Where the Phillies would be without McBride this year is tough to comprehend.

There is still not enough systematic moving of runners. There is still not enough making contact when contact is needed. There is still not enough consistent adjustment to the types of things they must do to win.

But the Phillies still can – and probably will – right themselves from this cliff-dive. One thing they haven't done all year, however, is string together a long winning streak. And they will need one if the Pirates go into their annual second-half runaway, as it appears they might.

The Pirates are, as always, looser than John Belushi. Meanwhile, the atmosphere is more relaxed in a courthouse than it is in the Phillies' clubhouse.

Both Lerrin LaGrow and Luzinski have charged recently that the Phillies are not having much fun playing. And they have blamed their manager for the pressure cooker in their locker room.

The question is: Is it the fact that Dallas Green yells at them that bothers them? Or is it that they just don't want to hear the truth?

NOTES: One positive sign for the Phillies is the rapid recuperation of Larry Christenson from his May elbow surgery. Christenson should throw batting practice for the first time during this homestand. And it is possible he could be activated within a couple of weeks. That, said Green, is if he has “no setbacks at all.” One thing Green will not do is send Christenson to the minors temporarily.

The unflappable Manny Trillo

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

There are 10 things hardly anybody knows about Jesus Manuel (Manny) Trillo.

(1) He was almost the world's first 140-pound catcher.

(2) Bowie Kuhn once sent a policeman to evict him from the Oakland A's bullpen during the 1973 World Series.

(3) He met his wife after she ordered a Miami airport security guard to check through his clothes.

(4) He is the first Latin American baseball player in history to prefer cold weather.

(5) He believes the main reason he never hit .300 with the Cubs was that they made him get up at 8 a.m. to play all those day games.

(6) Only three base runners in his entire career have attempted to take him out while he was turning a double play.

(7) He has pitched two games in his life. He struck out 14 batters in the first. He struck out 15 in the second.

(8) His least favorite city in America is Huron, S.D.

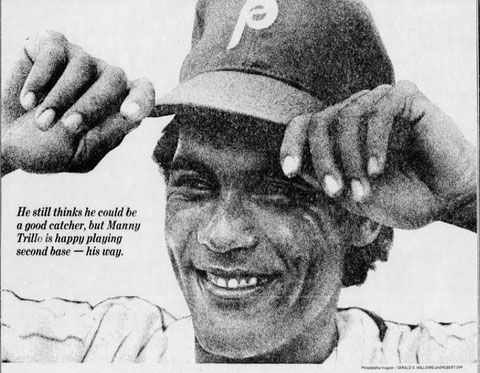

(9) He still thinks he would make a terrific catcher.

(10) He also believes he is the best second baseman in baseball.

"Ooh," says the normally mild-mannered Manny Trillo after this last pronouncement. "Look how fresh I am."

•

Manny Trillo has had approximately 2,567,000 fewer words written about him than Darryl Dawkins.

He has a lifetime total of zero magazine cover-photo appearances.

He has never done a national TV commercial, never been interviewed by Brent Musberger, never attempted to swim the English Channel on "Superstars."

Almost nobody outside Philadelphia knows much about Manny Trillo. Almost nobody inside Philadelphia knows much about him, either.

This is difficult to understand. Because even if he were not hitting .323, there is still no Phillies player who is more fun to watch than Manny Trillo.

There are probably two reasons for this.

One, he is one of the coolest people who ever wore a baseball glove. Two, when they begin ranking history's perfect body parts, Manny Trillo's arm is going to be right there with Betty Grable's legs, Rollie Fingers' mustache and Groucho Marx' eyebrows.

•

There are throws and then there are Throws. And when Manny Trillo throws a baseball, it is an event to rival Julius Erving's dunking a basketball.

For Trillo, The Throw is not merely a means of transporting the ball somewhere else. It is a show, a production, a truly original exercise in style. One Trillo throw is worth about 1,000 of Ted Sizemore's.

Forget for a moment that Trillo is as good at catching the baseball as any second baseman alive. Once he has caught it, that is the time to start watching.

He gets the ball in his glove. He stands nearly upright. He yanks the ball back out of his glove and raises it to his eye, like a jeweler examining a diamond.

Mark Fidrych talked to baseballs. But surely, Trillo knows them more intimately. Before he can throw a baseball, Trillo must look at it.

What is he looking for? Chub Feeney's signature? Small hidden photographs of the Pope? A secret message from the stitch-makers?

No, says Trillo, he is not looking for anything. This is just a psych device he invented many years ago, a device that even predated his life as a second baseman.

"When I used to play third base," says Trillo, "I used to dive for the ball, then get up and throw the ball over the stands. So now what I do is just take my time."

Time, however, is all relative in baseball. Time is one thing to a second baseman.

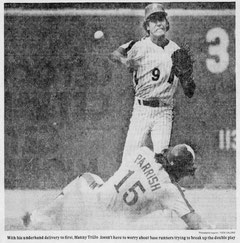

If circumstances are right, Trillo will stand there for a second, for two seconds, maybe even for three seconds. And only then will he finally whip the ball, in that unique underhand motion, to first base. In one particularly inspired moment in St. Louis this month, he even did a 360-degree turn before letting the ball go.

But time is something very different if you are a batter-turned-base-runner. You know you have just hit a routine ground ball. You know it is probably not necessary to run to first all-out.

But there is a problem when you have just hit the ball to this second baseman who is standing there, refusing to throw it. And so you must run. All 90 feet. Full speed.

And yet you know that when you have run 80 of those 90 feet, this cannon arm will unfurl and bam – you are out anyway. It is not unprecedented, therefore, to see people running down the line screaming after they have hit the ball to Manny Trillo.

"I remember one time," Trillo says, "Bill Russell (of the Dodgers) hit a ground ball at me. All the way to first, he was yelling at me, 'Throw the gul-damn ball, throw the gul-damn ball.'"

Trillo laughs at all this. But he knows that he is sometimes misunderstood because of it. Players on other teams sometimes think he is trying to show them up with this throw routine. But you have to know Manny Trillo to know this is unthinkable.

"I don't try to be cute or anything like that," Trillo says. "It's just my style. When I look at the ball, all I'm really doing is looking at the ball. I do it to everybody.

"I always say that if I get the ball and I know I'm going to throw the guy out, if I know for sure I'm going to throw the guy out, I don't want to take no chances. But nobody has ever beat one out on me like that, either. I don't let it get that close. They get three steps away, then boom.

"Fans, especially, don't understand me. They sometimes come and tell me, 'You're such a hot dog.' I say, 'Why?' They say, 'Because you hold the ball so long. Here I am in the stands thinking, "Throw the gul-damn ball.".. I just say, 'That's the way I play.' Nobody is going to change the way I play."

When Manny Trillo says nobody, he means nobody. When he was a Chicago Cub a few years ago, Cubs , general manager Bob Kennedy tried to convince him to throw in the more classic overhand style of other in-fielders.

"He called me in and tried to show me," Trillo says, still indignant. "I just said, 'I don't think there's nothing wrong with me.' I said, 'Nobody is gonna change my style.' I think I stayed in there with him about two minutes."

•

The ultimate moment in Trillo artistry occurs when Senor Trillo is turning the double play.

And to Philadelphians, it became clear these double-play relays would be extraordinary events right from the beginning.

In Trillo's very first Veterans Stadium game as a Phillie, someone hit a slow chopper to Mike Schmidt at third. Schmidt flipped to second for a force-out, and everyone in the park relaxed.

Everyone except Trillo, that is. The ball was hardly in his glove before it was out of his glove. That 12-billion-horsepower arm unleashed it to first in what seemed like a thousandth of a second. Double play. People who had never seen this act gasped openly.

"He's probably the best at turning the double play that I've ever seen," says his manager, Dallas Green. "He has the quickest feet, the quickest hands and the best arm. He turns some unbelievable double plays. You just can't say 'no chance' with Manny."

For years it has been generally conceded that former Pirates second baseman Bill Mazeroski was the all-time classic double-play man. But Phillies coach Mike Ryan, a former Pirate, says Trillo is "as quick or quicker than Maz. Maz was quick," says Ryan, "but he didn't have the arm Manny has."

It is the arm that truly makes Trillo the awesome double-play turner he is. Not only is his arm as strong as anybody's this side of J. R. Richard. But there is also the matter of that underhand delivery.

The runner who tries to go in hard on Trillo risks having a submarine ball bore through his head. Trillo isn't exactly built like Bill Bergey, so he developed the underhand relay throw as a defense weapon. Surface-to-air missiles should work as well.

Even the Phillies' Lonnie Smith, maybe the most fearless double-play takeout slider around, says Trillo is the one guy he won't challenge. Smith found that out the hard way one winter in the Venezuelan League.

"He scared the hell out of me twice," Smith says. "I tried, but he's just too quick. All you can do is dodge the ball. Afterward, he told me to be careful on him."

Takeout slides on Trillo are so rare that he actually can recount every one attempted in the big leagues. Of course, there are only three.

The Braves' Gary Matthews was the first. He even recorded an official knockdown. But it was also after the play, after Trillo had taken the force, given up and taken a few steps beyond the base.

"I was mad," Trillo says. "I don't think his mind was in the game at the time. He couldn't have been trying to break up the double play, because there was no time to even make the double play."

Next to complete a successful takeout was Houston's Enos Cabell.

"It was really my fault," says Trillo. "We play winter ball together. The guy is my friend. So I didn't think he would try me. But he knocked my butt down real good, too."

Takeout No. 3 was recorded by the Mets' Steve Henderson last year. Of course, in that case, the only person who realized it was a takeout was Trillo.

"He didn't really knock me down," Trillo says. "He just slid at my feet. I put that like he knocked me down, though – because he touched me."

Nobody, you see, touches the great Trillo.

The most successful obstruction of a Trillo relay throw actually was pulled off by a guy who never came near him. The ever-resourceful Phil Garner of the Pirates slid into second earlier this year and threw his hands up like a guy trying to block a Tony Frisch field goal.

Garner deflected Trillo's throw into right field. It was one of only three errors he has made all season.

"At first I was mad about it," Trillo says. "But after a while I realized there was nothing I can do about it. I think now that I tried to get rid of the ball too quick."

When your only problem is that you are sometimes too quick, you know life could be tougher.

•

What makes Trillo's second-base genius even more remarkable is that he was a catcher until 1968 and never played second regularly until 1973.

He came out of Cartito, Venezuela, as a rail-thin catcher. The scouts started to notice him in 1966. He was only 15 then.

"Probably at that time I weighed about 110 pounds," he says. "I remember the time a guy wanted to sign me. All he told me to eat was steak and milk. I didn't do it."

He finally signed with the. Phillies in 1968 for the astronomical bonus of $500. He didn't care – "I was so interested in playing baseball. And at that time Latin guys didn't get that much."

He arrived in spring training and was assigned to the Phillies' Class A team in Huron, S.D. His very first professional manager was a guy named Dallas Green.

It was the first time he had ever left Venezuela. But even then Manny Trillo was cool.

"Like I always say, I take it the way it is," Trillo says. "At the beginning I say, 'Oh, I miss my mom; oh, 1 miss my family.' But after a while I got to realize that, well, here I am, I'm in another country. If I want to be good, if I want to do good, I've got to forget about it and not be homesick."

Once that problem was licked, the next dilemma was where this guy was going to play. It wasn't tough to discern he didn't have your classic Johnny Bench catcher's physique. Even now, he carries only 164 pounds on his 6-foot, 1-inch body.

"I can still remember him," says Phillies vice president Paul Owens, then the club’s farm director. "He was such a skinny little guy. He looked like the wind would blow him over."

Trillo still thinks he was a good catcher. He knows he had the arm. He knows he had the hands. He does admit that things like knuckleballs gave him trouble.

"I remember the time I was catching Charlie Hough in the winter league," Trillo says. "He gave me the big glove, so I could catch him better. There was a guy on first base, and he throws me the knuckleball.

"You know how knuckleballs come. I had no idea what to do. I just turned around to see where the ball was. It turned out the ball was in my glove. The runner on first thought I was joking. I got a lot of kidding about that."

But knuckleballs or no knuckleballs, Green took one look and knew it was time to find Manny Trillo a new position.

"I just knew down deep he wasn't going to be able to stand the rigors of catching, day-in, day-out," Green said. "I thought he might make a pretty good infielder. I wasn't smart enough to think about second base."

So Green made Trillo a third baseman-shortstop. But he didn't become an accomplished infielder overnight. He couldn't catch every day and so he played just 35 games. He played only 83 at Spartanburg the next year. And the Phillies lost him to Oakland that winter in the minor league draft.

"I don't think we were overly concerned at the time," Green says. "He was so young at the time, we just didn't know how he was going to develop."

But in the Oakland chain he got to play. They switched him to second base in Tucson in 1973, his second year in Triple A. He hit .301 in Triple A one season, .312 the next, and there he was in Oakland in September.

He got 12 at-bats, then just stuck around as a spectator as the A's roared into the playoffs and World Series.

But suddenly, after the first game of the Series, he wasn't just a spectator anymore. A's second baseman Mike Andrews kicked around some ground balls in the first game, so Oakland owner Charles Finley decided to waive him immediately and activate Trillo.

Manager Dick Williams decided it would be best not to play him until the commissioner decided whether the whole thing was legal. So Trillo headed out to the bullpen to watch Game Two. Next thing he knew a New York City cop was out there asking for him.

"This guy said, 'Where's Manny Trillo?' " he recalls. "I said, 'Here I am.' He said, 'There's a policeman coming to get you.' I don't know why they didn't just send a bat boy."

He didn't play in the Series. The commissioner ruled Finley's move illegal. He didn't play the next year after he had replaced the injured Ted Kubiak, either.

It was the closest he ever got. A week after the Series, he was traded to the Cubs in the Billy Williams deal.

•

It was in Chicago that the legend of Manny Trillo, the fearsome spring hitter, first grew.

On May 9, 1977, Trillo was hitting .388, first in the National League. He eventually faded to .280. But the thing is, Latin Americans are supposed to do their best hitting when the weather is hot. They're supposed to be used to the heat, right?

But all of Trillo's best stretches as a hitter always came during the first two months. "I know I could lead the league the first two months every time," Trillo chuckles.

For a long time, it was assumed that the reason Trillo always blazed in April and melted in July was that seething Wrigley Field day-game heat. Just a seepage of strength or something like that.

But now it turns out it was nothing that complicated at all. Early to bed and early to rise might have been great for Ben Franklin. But it never worked well for Manny Trillo.

"You have to get up at 8 o'clock over there," Trillo complained. "But with me, I like to watch TV late. If the movie is good I'll be watching it all night. Then the next day I feel bad.

"In Chicago, when you play the day games, you want to go out at night. You don't get out of the games and go to bed at like 7 o'clock. The bad part is that you have to wake up the next day, at the latest, 9 o'clock in the morning. Hey, I'm a late sleeper."

This might sound crazy, but Trillo contends it affects many more guys than you would imagine. "How many guys have good years in Chicago?" he says. "Kingman, that's all."

There may, of course, have been other factors. One, says Trillo's teammate in Chicago, Greg Gross, is that the Cubs wanted Trillo to be a major run-producer. He was even known to hit cleanup now and then.

"He was always hitting fifth there because they didn't have anyone around him," Gross says. "Manny is a guy who should be hitting second or seventh, where he can get on base, move runners.... Now he's in a lineup where they better utilize his talents."

There was another thing. It has long been a Cubs tradition to play like the '27 Yankees the first half of the year, then settle into their fifth-place groove thereafter.

Well, Manny Trillo is a pennant-race guy. Being 22 games out in August is not his idea of motivation.

"When the games mean something, it kind of pushes you more," he says. "I don't know how you play in Chicago when the other team always gets eight runs in the first inning."

•

It is nearly August, and he is hitting .323. It is nearly August, and he is still hanging with the league leaders.

He has had every opportunity to fade. He sprained an ankle in April and missed three weeks. He jammed a finger in July and was out three days. He has hit second. He has hit fifth. He has also hit sixth, seventh and eighth.

None of it has bothered Manny Trillo. He just keeps slapping those hits to right-center, bouncing hit-and-run singles through the holes, pulling doubles down the line.

"There's no difference to me between eighth, fifth, sixth, second," Trillo says. "The only difference would be if I'm not in the lineup.

"Even when you hit eighth, you're gonna get a bad pitch or a good pitch. All you got to do is, if you get a good pitch, you swing at it. I guess you're not supposed to get good pitches when you hit eighth. But it's his (the pitcher's) fault. It's not my fault."

The prospect of actually leading a league for an entire year would not even enter Manny Trillo's head if people didn't keep asking him about it.

"I just don't want to get that in my mind," Trillo says. "The only thing I look at in the paper now is the standings. I don't even want to look at the scoreboard now when they've got my average up.

"I just don't want to get where I hit and then go in the field and worry about whether I go up two points or I go down three points. I don't want to take that with me. Now if I go 0-for-4, I say there's nothing I can do about it."

•

He is a very cool person, this Manny Trillo. Hardly anything, except fastballs aimed at his earlobe, can shake him out of that perpetual calm.

"Luzinski came to me once," Trillo says. "He say, 'Why are you smiling all the time?' I said, ‘I don't know. I'm just happy that way. What should I be mad about?' "

What indeed? Manny Trillo doesn't even have to play this game if he didn't want to.

He met his wife while waiting for a flight home to Venezuela one fall. And she turned out to be the daughter of a wealthy Venezuelan banker, with holdings in oil and real estate.

"They (her parents) are the ones that have the money," Trillo says. "We don't have it. But do I have to play? No. I play just because I like baseball.

"It's not that because I have everything I want I wouldn't try that hard or nothing. I just love to play. I go back home in the winter, and I still play ball."

People misjudge that nonchalance sometimes. But beyond the nonchalance there is a sense of style, a showmanship one hardly sees anymore.

So he may not get worked up when he doesn't make the All-Star team. He may not change expressions when a Luis Aguayo starts looking as if he might threaten his job. He may not throw helmets when a call doesn't go his way.

But that is Jesus Manuel (Manny) Trillo. He takes it the way it is.

"I'm just cool," says Manny Trillo. He is smiling as he says this. Of course.