Chicago Tribune - June 1, 1980

Hernandez only Cub to erupt

By Robert Markus

CHICAGO – CUB FANS MUST have made the Philadelphia Phillies feel right at home Saturday. They booed the home team. Not as well or as lustily as the Phils are accustomed to being booed in their own park, of course. But, then, their team didn't play as well or as lustily as the Phils, either.

While 26,937 long-suffering paying customers were venting their displeasure at the Cubs' lusterless 7-0 loss to the Phils, at least one Chicago player was letting off a little steam of his own.

Willie Hernandez punted his glove into the box seats and hurled a chest protector all the way to the third-base line after being lifted in the fourth inning.

IT IS A temptation to say that was his best pitch of the day, but Cub Manager Preston Gomez, whose back was turned to the temper tantrum, defended his starting pitcher.

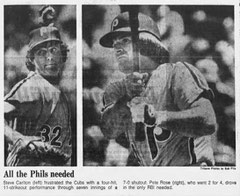

"I though Willie threw the ball good," said Gomez. "But the other guy pitched better." The other guy was Steve Carlton, who simply overpowered the Cubs, striking out 11, yielding but four hits, and walking none in seven innings.

He was awesome today," said Phils' Manager Dallas Green. "He's in such a great groove I get tired of talking about how good he is."

GREEN APPEARED to be taking pity on the Cubs when he lifted Carlton, partly to give reliever Dickie Noles some needed work, but Noles fanned Mike Vail and Jerry Martin to end the game, raising the toll to 13 and bringing out a final chorus of boos.

Others who brought grief on the Cubs Saturday were Mike Schmidt, who slugged a pair of homers, bringing his major league leading total to 16, and center fielder Garry Maddox, who caught just about every ball that didn't end up in catcher Bob Boone's glove.

The Cubs more or less brought the rest on themselves. Third baseman Steve Ontiveros missed a groundball he thought he might have had, and it went for a double that opened the gates for the Phils' three-run third.

VAIL, PROMOTED to the starting lineup, fanned three times and made a senseless and off-target throw that leaked in a run during the three-run fourth that put the Cubs, if not their fans, out of their misery.

Still, it all comes back to Carlton, who became the major leagues' first nine-game winner. "The only way you can beat him is to catch him when he’s not on," said Ontiveros. That happens about as frequently as Mayor Byrne smiles in public.

"He hasn't pitched a bad game all year," praised Boone. "His fastball has been just overpowering."

The Cubs, however, were uncommonly docile victims, reaching the epitome when Dave Kingman tried to bunt his way on base when he led off the ninth with the team trailing by seven runs.

CARLTON FANNED at least one in every inning, set the side in order three times, and never permitted more than one runner in an inning.

Hernandez got by the first two innings before running into big trouble in the third. Rookie Lonnie Smith rapped a grounder towards Ontiveros that "was not hit as hard as I thought it was," said the third baseman. "It came up on me at the end and went over my glove."

It caromed off his chest for a double, and when Pete Rose's grounder took a hop over Lenny Randle's glove at second, Carlton had the only run be needed.

He got two more immediately when Schmidt hit an opposite-field homer that bounced on the right-field catwalk.

The first two batters reached base against Hernandez in the fourth, and Gomez must have already made up his mind to lift the pitcher because after Carlton sacrificed, he headed for the mound.

HERNANDEZ MADE for the dugout at a brisk trot, then suddenly went into his amazing act. "I didn't hear say anything to him," reported coach Cookie Roias. "I think he was just mad at himself." Willie couldn't have been feeling much better after watching three more runs cross the plate on singles by Smith and Greg Luzinski - plus Vail's embarrassing throw - against successor Lynn McGlothen.

For Rose, streak always will endure

By David Israel

CHICAGO – THIS WOULD NOT MAKE a bad ballclub, this list In the morning paper. Joe DiMaggio, Pete Rose, and Willie Keeler; George Sisler, Ty Cobb, and Tommy Holmes; Dom DiMaggio, Heinie Manush, and Rogers Hornsby. Not much pitching here, but these are the guys who knew to heed the advice of the sagacious Mr. Keeler, the Wee Willie of baseball lore who made the original discovery that the best place to hit a baseball is "where they ain't."

Pete Rose studies the list. It is a pleasure. It helps him recall a time, not yet two years past, when he captivated America. The only name above Pete Rose on this list is Joe DiMaggio. In 1941, Joe DiMaggio got hits in 56 consecutive baseball games. From June 14, 1978, until the evening of July 31, 1978, Pete Rose hit in 44 consecutive games.

Now Rose rustles his newspaper and points to a few of the names on the list. They are names off the plaques on the wall in Cooperstown, names from the Hall of Fame. They serve as a vivid reminder of time gone by, just as the achievement of a certain Ken Landreaux does.

"This is where it really is going to start getting heavy," Pete Rose says as he points. "If it gets to 34 or 35 games. When he starts passing guys like Ty Cobb and George Sisler and Rogers Hornsby."

Rose, who knows more about the pressures of a long hitting streak than anybody else still in the business of playing baseball, is imagining what it is going to be like if Landreaux can keep this up. As he speaks, at the beginning of the weekend’s baseball activity, Landreaux has hit in 30 consecutive games. Within hours, he will have hit in his 31st. Rose cannot know now that on Saturday afternoon a clever little left hander for the Baltimore Orioles named Scott McGregor will end Landreaux's streak in the 32d game.

THE WELL PUBLICIZED end of the streak on national television cannot diminish the grand quality of Landreaux's achievement. Only 22 other players in major-league history have done as well. The streak is virtually certain to stand as the season’s longest. Last season it would have been the most lengthy by eight games-surpassing the 23-game streak of one Pete Rose. Making the feat all the more noteworthy was the fact that Landreaux succeeded where no one else did - on the Minnesota Twins, a team with the worst record in the American League.

Rendering the feat all the more fascinating was that Landreaux, laboring in the quiet obscurity of the North Woods, was mounting a challenge to break baseball’s most treasured record, the one, they say, that was not made to be broken. Ken Landreaux was trying to get his name listed ahead of the names of baseball legend and American folklore, ahead of DiMaggio, the silent, silken star who both played and lived with uncommon grace, who won championships and Marilyn Monroe's heart; ahead of Rose, the workingman's player; ahead of Sisler and Cobb and Hornsby.

If the streak had continued for Landreaux, he would have discovered the momentum of such success to be of no value. A single in game 38 might have been as difficult to come by as three hits in game 12. For Pete Rose, that made it all the more rewarding. Every pitcher fashioned himself as the incorruptible gunslinger who was going to come into town and finish off the rampaging desperado. Rose was presented with a challenge, and he met it.

IT IS WITH GREAT fondness and zeal that Rose, who 'entered June on a tear for the Philadelphia Phillies, recalls that summer of '78, when he was on the most memorable rampage in the history of the Cincinnati Reds and the National League.

"I was having fun," Rose says now. "I. was doing two things-I was getting hits, and I was scoring runs. I was doing my job.... I hit in 25 games before the All-Star break and 19 after. People started to notice during the All-Star break because 27 was the team record in Cincinnati. Then I started to get followed pretty heavy because the National League record was 37 by Tommy Holmes. Then it happened that I went to New York to tie and break that record, and Tommy Holmes was working for the Mets."

While Pete Rose was having fun, so was everyone else, save those gunslingers in the opposing uniforms who were as unsuccessful as they were incorruptible. On those three nights he played in New York and chased Holmes' record, the Mets attracted 110,000 spectators, 10 per cent of their entire season attendance. On a Sunday in Cincinnati, he hit in his 44th consecutive game. The next evening, the Reds went to Atlanta. That afternoon, the Braves sold 29,000 tickets to walk-up customers.

But while Rose was having fun, he was also having some anxious moments. He was not particularly lucky during the streak. He just was hitting the ball hard. He only struck out four times in 188 at-bats. Even the night the streak ended in Atlanta, Rose hit a couple of smashes. On one line drive, a pitcher named Larry McWilliams grabbed the bail while stumbling and looking in the opposite direction. On another, the ball almost drilled a hole in the midsection of third baseman Bob Horner.

ONE NIGHT IN Philadelphia, though, Rose did come by some good fortune. He was hitless when he came to bat in the eighth. The count went to 3-2. He checked his swing and walked. It looked like the streak was over. But in the ninth inning, the Reds batted around, and Rose got a bunt single.

For anyone to challenge the records of DiMaggio and Rose, there must he games such as that improbable one in Philadelphia. Landreaux could have done with one in Minnesota Saturday afternoon. There must also be times when a fellow who is hitless in three trips is not given the take sign on a 3-0 pitch in the ninth inning. There must be a perfectly fortuitous melding of the interests of the individual and the interests of the team.

"I tried never to put the streak ahead of the team," Rose says. "I don't think you can ever put something personal ahead of the team. The strange thing is that Landreaux's streak isn't helping the team and isn't drawing any people. Mine brought in a lot of bucks for everybody."

For Pete Rose, the hitting streak salvaged the of '78, a summer that was soured by a contract dispute with Reds' management and the collapse of the ballclub; a summer that, otherwise, was not one of terrific achievement for Rose. He batted a measly .302; he did not have 200 hits.

BUT HE DID HAVE the streak, the magical six weeks when no one could deny him - not Steve Carlton or Vida Blue or Don Sutton; the magical six weeks when all America was enchanted by his race against logic and his brush with immortality.

"There really wasn't any pressure on me," Pete Rose says. "Once I got up around 35, no one was going to say I choked. I really was having fun. On the night it ended, I had a friend In Florida who was at the Sarasota Kennel Club for the races. The public address announcer got on the loudspeaker and said he had some good news and some bad news. 'The good news is that the Sarasota Kennel Club is open for matinee racing tomorrow,' he said. 'The bad news is that Pete Rose's hitting streak ended tonight.' Everybody booed."

Now, almost two years later, Pete Rose just smiles.