Philadelphia Inquirer - March 23, 1980

Can baseball fans identify with $140,000 strikers?

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

CLEARWATER, Fla. – The sounds were the thwacks of batting practice on a cool, wet Florida morning.

Thwack. Silence. Thwack. Silence. Thwack. Silence.

No game. No action. No drama. Just a pitcher grabbing a ball and throwing. Just a hitter swinging and driving it someplace. Just the basic sounds of baseball, ringing through a quiet stadium.

Thwack. Silence. Thwack. Silence.

Ruly Carpenter sat in an empty office at Jack Russell Stadium and looked out the window. What got him was the sight of people actually hanging around, watching this. Watching batting practice in a stadium where no game was scheduled.

Ruly Carpenter shook his head at the appeal of his sport.

"That's really what it's all about," said the president of the Phillies. "You see people at spring training watching this game, they don't want to read about salary disputes or labor disputes. But they do want to watch these ballplayers.

"And if they can't," said Ruly Carpenter, "they might become extremely upset. That's what concerns me."

Eleven days remained as Ruly Carpenter spoke these words, 11 days until baseball's Major League Players Association was scheduled to gather its executive board for a meeting in Dallas.

Fears impact on fans

There is every indication they will vote to call a players' strike that day – maybe immediately, -maybe for Opening Day, maybe for Memorial Day. They will head for the picket lines instead of the foul line, and Ruly Carpenter fears baseball will never be the same if that happens.

"A strike, in my opinion, would have a disastrous impact on fan interest," Carpenter said. "I think it will be far worse than that short strike we had in 72.

"In 72, the average major leaguer's salary was probably $25,000 to $35,000. Today it's more like $130,000 or $140,000. It's been said many times in the past couple of weeks, but I have to say again – it's extremely difficult for a fan to identify with a guy making a salary of $130,000 or $140,000 going on strike.

"In 72, maybe the fan could say these guys are professionals, they're skilled guys, maybe they deserve to make more money. But now they see the average salary is five times or six times what the average income is in the United States today. And they're on strike."

Even if the issues are far more complex than that, it is the money that is going to be flashing in front of the common guy's eyes. It is the money that is going to be the turnoff.

Will anybody perceive that this is any different from a strike by Dustin Hoffman and his movie-star buddies? Or Christiaan Barnard and all the world's doctors? Or F. Lee Bailey and the lawyers?

Ruly Carpenter doesn't think so, and the thought that scares him is of people suddenly regarding Mike Schmidt and Pete Rose as labor villains instead of baseball heroes. What happens to the sport if players aren't people to look up to any more?

"If there is a strike, and the fans get turned off to the players, the owners lose, too," Carpenter said. "The players are what we're selling in this game.

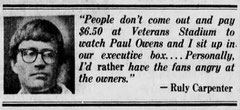

"People don't come out and pay $6.50 at Veterans Stadium to watch Paul Owens and I sit up in our executive box. The people they identify with are those guys on the field. And I think that if there is a strike, the turnoff to players is going to be bigger than it was in 72. A lot bigger."

These are the words of an owner to be sure. But they come with regret. Carpenter will take his stand with the other owners because he has to. But it is his players he will be bleeding with, the way he always has in the simpler games of the baseball field.

All around him, fans and owners may be pointing fingers at the players. But Carpenter will point his at his fellow owners.

"Let's be honest. We're the ones who created this salary structure, not the players," Carpenter said. "Personally, I'd rather have the fans angry at the owners. We're not the people they pay to come see."

Carpenter has contributed in a small way to the salary-escalation madness. He did indeed give Pete Rose his $900,000 a year. And that most certainly set a standard for the typical baseball superstud.

Carpenter foresight

But it wasn't Ruly Carpenter who stuffed million-dollar bills into the pockets of John Curtis and Dave Goltz. Carpenter has been able to stay out of the free-agent sweepstakes because he used a little foresight and signed up most of his division-championship nucleus just before the reentry age hit in 1976.

So he had the team he wanted. He didn't have to run after the free agent of the week.

"In 76, we bid on some of those reentry guys," Carpenter said. "We bid for Don Gullett, for Joe Rudi. We were involved. But we were just blown out of the saddle. Right then I said, my God, there's no way this can keep going on.

"But the next year It was a little worse. And the year after a little worse. And this year there was more money spent, per player, than in the history of the free-agent draft. And this was not for a Pete Rose, whose signing I feel was justified for the Phillies. This was to other players of lesser abilities. Maybe these owners feel they can justify that. But I couldn't."

The long-term contracts his stars signed in the late 70s will expire gradually over the next couple of seasons. And Carpenter may not be able to make the same choices he made the last time. This time he might lose a few guys instead of paying them.

The Garry Maddox case is the most visible example of that. Carpenter says the contract he has offered Maddox is "extremely fair, even based on today's market values." But Maddox, who could become a free agent in October, is seeking what he thinks free agents will be demanding then.

Criticizes colleagues

"There might be some owner – if some of my peers even deserve to be called owners – who are going to pay him what he's asking for," Carpenter said. "There's every indication that's going to happen. That's the reason, basically, we 'can't get together."

Carpenter insists Maddox is not being hard-lined to serve as an example. It is simply that Carpenter has an idea of what salaries ought to be, and he thinks "I know when to stop." So he may make his stand. But all it takes is one owner who will give Maddox his $900,000 a year, and the salary elevator goes up another floor.

And yet the owners then go to the bargaining table and plead poverty. They are making tough demands, but the people they really are seeking to control are themselves. The answer isn't a strike, says Ruly Carpenter. The answer is for both sides to realize the long-term financial implications of a salary scale run amok.

"People just have to show some common sense," Carpenter said. "People have got to realize this salary structure just isn't feasible. Some day, the balloon's going to bust."

Carlton goes 5, Phils coast, 3-0

By the Associted Press

CLEARWATER, Fla. – Steve Carlton pitched five scoreless innings yesterday as the Phillies shut out the Houston Astros, 3-0, in an exhibition game. Carlton allowed three hits.

Larry Bowa scored the first run in the third inning, reaching base on an error, moving to third on a single by Carlton and scoring on an infield out. The run came off losing pitcher Joe Niekro.

Reliever Ken Forsch gave up the other two runs in the seventh. Greg Gross singled to left and scored when Garry Maddox followed with a double to deep center. Maddox advanced to third on an infield out, and scored when Bowa laid down a perfect squeeze bunt.

Owners’ stupidity and players’ greed are basis of contract impasse

By Allen Lewis, On Baseball

As time goes on, it seems more and more evident that the club owners, as a group over the past 14 years, have been stupid, and the ball players have become greedy. A threatened strike when baseball interest is at a peak and the players are being rewarded as never before is an indication of how stupid and how greedy.

If, more than a decade ago, the owners had not spent so much effort trying to discredit and get rid of Marvin Miller, the highly successful executive director of the Players Association, and instead had said, 'OK, the players have maybe the top "union negotiator in the country in Miller, let's go out and hire the best negotiator we can find to represent us," they would not be in their present fix.

The stumbling block in current negotiations is something the players gained and the owners now want to take back – pure free agency after six years experience. In labor negotiations, that's as difficult as finding a 20-game winner in the minor-league draft.

The free-agency question, and the question of how much contributions to the pension fund should be increased, are the real issues that could lead to a strike. The owners' proposed salary scale, withdrawn this week, was never regarded by either side as a serious proposal.

The players maintain, however that if compensation is required when a player moves as a free agent to a new team, it will mean almost no movement. They cite pro football as an example. But there is a significant difference between pro football's system and the one proposed by the baseball owners.

A football team losing a free agent must receive talent of equal ability and, if the two clubs cannont agree, the commissioner decides which player or players shall go to the team losing the free agent.

A baseball team losing a free agent will get to choose one player after the other team has frozen 15 players, including all those with no-trade contracts. If that rule had been in effect when the Phillips signed Pete Rose, the Reds would have been able to pick one player off the Phillies 40-man roster after they had withdrawn, for example their starting eight and their top seven pitchers. Losing one of the' other 25 surely would not have prevented the Phillies signing the future Hall of Famer.

Of course, there's nothing sacred about the number 15. There is room for negotiation there, making it 18 or even 20, and such a system would surely result in free agents moving to new teams, although not in the numbers of recent years.

As things now stand, a team, with limited financial resources continues to lose outstanding players while getting nothing in return but a draft choice. And a first-round draft choice in baseball is as different from a first-round draft choice in football as a piece of cut glass is a different from a diamond.

The players, of course, reject that argument. They say that if an owner can't afford to pay, let him sell the club to someone who can. And that will eventually result in complete corporate ownership.

As for the pension plan, the owners have offered increases that would pay a player with five years in the majors $5,500 a year at age 45 up to $20,000 at age 65; with 10 years in the majors $11,000 at 45 up to $40,000 at 65, and with 20 years almost $15,000 up to $50,000.

If the owners and players continue to disagree, they should settle their differences by arbitration. A strike could have disastrous consequences for both sides, would be unfair to the fans who pay the freight, and, all in all, is unconscionable.

•

The answer to last week's Trivia Question: Steve Carlton of the Phillies committed 11 balks last season to set the major league rofd for one season. The old record was eight, set by Bob Shaw of the Milwaukee Braves in 1963 and tied by Bill Bonham of the Cubs in 1974 and by Frank Tanana of the Angels in 1978. First with the correct answer was Joseph Meszaros of Pottstown, Pa.

This week's question: Who holds the major league record for games lost in one season by a relief pitcher?

Who, me?

A six-man panel rated Larry Bowa of the Phillies the National League's best shortstop in a poll for Sport magazine. Mark Belanger of the Baltimore Orioles' was ranked first in the American League. Garry Templeton of the St. Louis Cardinals was second in the NL, ahead of Dave Concepcion of the. Cincinnati Reds. Bowa commented, "Concepcion and I are the best right now, and modesty forbids my saying who is better."