New Jersey Newspapers - July 16, 1980

Camden Courier-Post

Phils’ loss puts Ruthven in doghouse

By Ray Finocchiaro, Gannett News Service

HOUSTON – Dallas Green may not be desperate enough to order a seeing-eye dog for pitcher Dick Ruthven, but he's busy running his fingers through the Yellow Pages looking for a good optometrist after last night's 3-2 loss to the Astros.

At least it's better than wrapping his hands around Ruthven's neck and squeezing.

The reason for the Phillies manager's dismay is Ruthven's apparent inability to see first baseman Pete Rose breaking toward the plate.

FOR LAST night, as Rose was rushing in on the plate with Houston's Craig Reynolds squaring to bunt, Ruthven wheeled and almost uncorked a wild toss to first base, which was embarrassingly devoid of any-one in Phillies' blue at the time.

Instead, Ruthven held the ball for a balk, sending Jeff Leonard to second, from whence he scored as Ruthven fielded Reynolds' subsequent bunt and, off-balance, flung the ball over Rose's head to end the game.

"If you're a pitcher, can't you see a guy breaking (for the plate)?" Green said incredulously, not having to be reminded that Ruthven did exactly the same thing against the Mets two weeks ago.

"THAT MEANS he's not paying attention. That's why half the guys steal on him – he can't see the bleeping runners. He must not be able to see. He's not seeing first base at all. If he is, he has to see the guy break."

Ruthven was not available to discuss his vision problem, throwing a few things around the Astrodome clubhouse and then retiring to the trainer's room to soak his arm.

"They're stealing on him, they're getting great leads and he's just not seeing it," Green said, rambling on to keep himself from joining the clubhouse destruction. "Part of your job as a pitcher is to hold guys on first. Sooner or later somebody's going to get to first on you. We can't have Pete breaking and his balking every five minutes."

GREEN'S ANGER at Ruthven was just part of his overall displeasure with still another breakdown in his grind-it-out "team baseball" concept.

"One of these days people will listen to me about grind-it-out baseball," said Green. "I don't know when, but they'll listen... they will if they want to win. Every single run they got tonight was a mistake on our part."

Well, two of the three, anyway.

THE PHILS had taken a 1-0 lead off gimpy-legged Nolan Ryan in the first on four singles. It might've been worse, but Manny Trillo, the league's top hitter, got caught in a rundown after singling to right.

Houston tied the game in the fourth with an unearned run. Terry Puhl snapped Ruthven's perfect game after 10 batters with an infield single to Trillo.

Puhl stole second, raced to third when catcher Bob Boone's throw skipped into center field and scored on Jose Cruz's sacrifice fly.

AFTER THE Phils had regained the lead with an unearned run of their own in the sixth, the Astros went to work on Ruthven in the last two innings.

They bunched three singles for their legitimate run in the eighth, then watched Ruthven self-destruct in the ninth.

Green simply shook his head when asked about Reynolds' game-winning bunt, which Ruthven fielded and arched over the leaping Rose. The pitcher's ungainly pirouette was reminiscent of the dive Ruthven took that injured his shoulder on June 13.

"WHAT GOOD does it do to make a play like that?" Green wondered. "You've got to shut it down, hold the ball and try to figure a way to win from there. The worst is, with guys on first and third. You've got no chance on the error.

"You can't be a hero in that situation. The one time it works doesn't make up for the 10 times you lose a ball game on it."

Ruthven wasn't alone in Dallas Green's doghouse. Del Unser, starting in left field against Ryan with Greg Luzinski at home with a sore right knee, had a corner to himself.

WHAT ANGERED Green was Unser's failure to advance Bake McBride with a bunt in the ninth. McBride had greeted lefthander Joe Sambito with a single to left and, instead of sending up Lonnie Smith to swing away, Green ordered lefty Unser to bunt.

Normally a good bunter, Del tried twice and failed, then swung away and hit into a double play.

"Unser not getting the bunt down was another example of not playing team baseball," said Green. "If he's gonna hit away, I'll pinchhit with a righthander, for heaven's sake!"

UNSER ALSO struck out with Trillo at third and one out in the sixth after McBride had gotten Rose home with the second run.

"We don't get a run in from third again," mumbled Green. "Team baseball. This game was a perfect example of how not to play team baseball. We play great baseball for seven innings and forget how to play it for two. That's how you get beat in these kind of games."

EXTRA INNINGS – Mike Schmidt was scratched with an aggravation of his pulled hamstring two minutes before the lineup was handed to the umpires... "Mike came in after hitting and it tightened up a little," said Green.

The Press of Atlantic City

Astros Edge By Phillies

Houston 3, Philadelphia 2

HOUSTON (AP) - Pinch runner Jeff Leonard scored the winning run in the ninth inning on a pair of miscues by Philadelphia starter Dick Ruthven Tuesday night as the Houston Astros downed the Phillies 3-2.

Alan Ashby led off the Astros ninth with a single. Leonard, running for the Houston catcher, took second on a balk by Ruthven. He scored all the way from second when Ruthven, 8-6, fielded Craig Reynolds' grounder and threw it away.

Joe Sambito, 4-1, picked up the victory with an inning of scoreless relief.

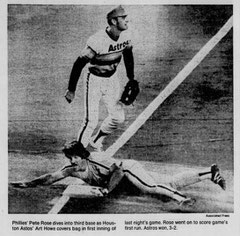

The Phillies greeted Houston starter Nolan Ryan with four singles that produced a 1-0 first-inning lead. Pete Rose led off with an infield hit and moved to third on Manny Trillo's single. Trillo was out trying to advance to second, but Del Unser's hit scored Rose.

The Astros evened the game 1-1 in the fourth when Terry Puhl ended Ruthven's 31-3 innings of perfect pitching with an infield single. Puhl stole second and continued to third on catcher Bob Boone's throwing error. Jose Cruz sent Puhl home with a sacrifice fly.

Ryan retired 13 Phillies in a row before Rose singled in the sixth inning. Third baseman Art Howe bobbled Trillo's grounder and threw it into right field, allowing Rose to go to third and Trillo to second. Bake McBride's grounder scored Rose.

In the bottom of the eighth, the Astros grouped singles by Rafael Landestoy, Puhl, and Denny Walling to knot the score 2-2. Landestoy scored when Walling's grounder got past Ruthven.

Lefty Carlton’s Superb, But Sometimes From Left Field

Los Angeles Times Service

PHILADELPHIA — The pieces of Steve Carlton are not so much a puzzle as a mosaic.

The person without a purpose, or a pattern, is the true mystery, no matter how much he talks.

Silence is no barrier to understanding, if it is a silence like Carlton’s, that is surrounded by a lifetime of consistent and eloquent facts and acts.

To many, the Philadelphia Phillie pitcher seems to be baseball's richest enigma: the Southpaw Sphinx who, by his defiant silence and cultivated eccentricities, invites himself to be the subject of observation and deduction.

Certainly, the behavior of the man who is the’ game's hottest pitcher of the moment is unique, and at first glance, inscrutable. Even Carlton's locker has no name or number above it, as though in the middle of a quasipublic place his space could be invisible, inviolate and devoid of any traces of personality.

"You have no right to look at my locker," Carlton said, his voice quivering with barely controlled emotion, a bat on his shoulder, as he sought out a reporter in the Philadelphia dougout today. "I heard you looked at my locker."

And so, drawn up to full height as though looking down at a hitter, Carlton lectured for several minutes — in the slightly off-center, out-of-focus manner of a man who is a bit daffy on one subject - on the crime of looking at his possessions from a distance without his express permission.

"You've made a big mistake,” he said over and over, with ominous mystery.

To those who don't know Carlton, the scene might have seemed irrational, sad or comic. It actually was calculate part of a deliberate pattern, and from Carlton's perspective, totally justifiable.

The 35-year-old, 6-foot-5 pitcher with the 14-4 record and the 2.21 earned-run average is, and long has been, a student of force, mystique and intimidation. He is in search of a solitary, self-contained superiority, and he has discovered a nearly perfect place for it: the mound.

Carlton's energies — sometimes even those that appear unrelated to baseball — are dedicated to bringing more powerful tools of body and mind to his hilltop.

For the sake of longevity and a trim waist in his baseball old age, the 219-pounder is a vegetarian.

For greater strength and leverage, better understanding of torque and the body's potential for building muscular tension, then releasing it in one explosion, Carlton is a disciple of the martial arts, kung fu in particular. He has, for four years, worked with a Phils trainer, Gus Hoefling, who loves to talk about “positive and negative tension" and, generally, play the role of jock guru.

“Carlton does not pitch to the hitter, he pitches through him," said former Phillie catcher Tim McCarver. “The batter hardly exists for Steve. He's playing an elevated game of catch."

Carlton is an introverted man of enormous intensity and pressure who is, while on the mound, seeking everything that is the opposite of his nature: peace, oblivious concentration, a trance in which he can reach deep add use all of his resources.

So he studies West and Eastern philosophies. He cultivates a private catcher with whom he has long discussions of every hitter so that their pitch-calling can be on the same wavelength with no distractions. Two minds as one, two ends of an exalted game of catch.

Because Carlton always has had a hair-trigger temper, a tendency as shortstop Larry Bowa puts it “to go crazy… but never in public, of course," the left-hander tries to categorically eliminate all factors that might disturb his work.

Umpires' bad calls are ignored. Fielding errors receive a slight, disgusted shake of the head and then are forgotten. The cheers or boos of the crowd are not acknowledged. Eye contact with hitters, even teammates, is avoided.

In everything, Carlton cultivates the impression that he is above the petty forces that influence others, a sort of baseball Zoroaster wrestling apart with the forces of evil.

In the Phils’ yearbook, 17 players have homey portraits of themselves with their wives and children. Only Carlton and his wife Beverly (“she's the person I most admire”) and his two sons are conspicuous by their absence.

In a survey of the tastes of the Phils, all 24 other players sought the regular-guy image by listing favorite songs such as “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain."

Carlton took every opportunity to isolate himself. Favorite musicians: Jascha Heifetz, Jean-Pierre Rampal. People you’d most like to meet: Socrates, Einstein, Thomas Jefferson, Napoleon, Jesus Christ, Gandhi.

There is no ideological common thread among these big names, except that most folks wouldn't know quite what to say to them over soup, and Carlton thinks he would.

One-upsmanship, a fine knack for gaining a psychological advantage, is a strength of Carlton's pitching, but it also extends to hobbies such as his wine connoisseurship. Dine with Carlton and he's the guy who spent last summer touring the wineries of Burgundy. You may like the bouquet, but he knew the grape personally.

Those who one-up Carlton merit his special attention. Johnny Bench is one of the few hitters who “own” Carlton. “I can read him. I can almost tell what’s coming,” Bench has said. “It’s like I'm thinking along with him."

Once, when Carlton was hunting with former teammate Joe Hoerner, Carlton missed a bird, then fired off a shot into the air.

“There," Carlton said out of left field. "That one's for Bench.”

Few men have brought greater raw skills to pitching, or husbanded them more admirably. Carlton is pitching’s rigorous, driven, art-for-art’s sake master.

“What distinguishes Carlton in his command of every pitch almost every time out," said Pittsburgh's Willie Stargell, who has faced him for 16 seasons.

“You can find a key to other pitchers: he can’t get his curve ball over tonight or he goes to his slider in a jam," Stargell said. “You find some thought that simplifies our job of getting a good pitch to attack.

"But Carlton won't discard a pitch or limit himself. He's always got the full arsenal going for him.

“Pitching is the art of destroying a hitter's timing,” Stargell said. “Carlton understands that. He can take a little off or put a little extra on all of his pitches.”

"Just when you finally feel like you're screwed in on that damn curve ball of his, along about your third or fourth at-bat against him, your eyes light and you think, ‘I’ve got you now, Lefty,’’’ Pittsburgh’s Phil Garner said.

“Then all of a sudden, it’s a different curve ball — he’s pulled the string and you're out in front and on your way back to the dugout again.

“Carlton's got great stuff, especially that slider down and in to right-handed hitters. But he's not really uncomfortable to hit against. What makes him so great — the best, I think — is that he flat knows how to pitch. He’s always got your mind messed up.”

On Saturday night here, the Phils released 2,883 balloons before the game — each the symbol of a strikeout conquest for the man who has more whiffs than any left-hander in baseball history. Those balloons were Carlton's cloud of glory.

"Carlton makes it look so easy ‘cause he's worked so hard,” Stargell said. "You can always tell an athlete who’s reached a point where he’s at peace with himself. You want your energy to flow, not to feel knotted. You don’t want to be too sharp. You don't want to be too flat. You just want to be natural.

“When you look at Carlton, that’s how he is right now."

If only Veterans Stadium could be emptied before each game Carlton pitches, his athletic life would be perfect. From his promontory, Carlton looks down at a world of smaller men, hitters who are brought to their knees as they flail at his slider breaking into the dirt.

Talent and knowledge, study and endless regimen, have come together once more for Carlton, just as they did in 1972 when his record was 27-10 with a 1.98 ERA and 310 strikeouts for a Phils team that played in an anonymity merited by its 97 defeats. That season the only Philadelphia games that mattered were the ones Carlton pitched.

Then Carlton, who meditates for an hour before he pitches, and jams cotton in his ears as he heads to the mound, had no need to seek solitude. Being a Phil sufficed.

But with the emergence of a Phillie powerhouse, with the doubling of attendance and the redoubling of media scrutiny, Carlton began to realize that, although he was standing on a mound, thousands of others were looking down at him, down from the cheap seats, down from the press box. The man who played for no one but himself and who accepted no judgment but his own found himself pilloried by non-athletes with beer bellies and cigars.

Why, in the playoffs of 1976-77-78, did Carlton win only one of four starts with an ERA of 5.79? In a town that loves to castigate, Carlton was lumped with the rest of the Pholding Phillies.

The Phils became a burned and gun-shy team, leery of their fans and press. Sometimes they ducked the limelight, hid from reporters in anterooms. And sometimes, when things were rolling, they basked in the glory.

Such vulnerability to glib public judgment was intolerable to Carlton. As early as 1975, the year the Phils became contenders, Carlton began closing his shell. And the silence deepened each year, until now it is complete.

“Baseball is a public game,” Bowa tells Carlton. “We owe them something.”

“It’s our game,” answers Carlton. “We only owe them our performance."

Carlton showing no signs of age (and with an as yet unrevealed knuckleball, years in the perfecting), may end his days as a 300-game winner and baseball’s all-time strikeout king.

Carlton willingly has opted to be baseball’s haughty dark lord.

So, we see that there are no secrets, dark or otherwise, in Steve Carlton’s locker. Neither money nor fame controls him. Neither victory nor defeat fazes him.

With cotton in his ears, he stares down from his mound at his catcher. The hitter has been removed. The crowd has been removed. Those who praise or blame him have been removed.

Carlton, in that moment of supreme intensity to which he subordinates all else, is a great thoroughbred — blinders in place — getting ready for a private game of catch.