Philadelphia Inquirer - October 26, 1980

Fans toot their own horn when they shout victory

By Julia Cass, Inquirer Staff Writer

Those exuberant Phillies fans who shrieked at the stadium and on the street, "We're number one! We're number one!" actually meant "I'm number one!" They were telling the world and each other: "Philadelphia just won the World Series. I'm from Philadelphia. Therefore, I'm a better person."

This is the underlying message that Thomas Tutko, a psychologist from San Jose State College in California who has written six books on, sports psychology, read between the shouts.

Tutko watched the Series on television and he noted, as many other people did, that Philadelphians individually and Philadelphia as a city seemed to experience an "immense psychological uplift" from the World Series victory. In a telephone interview late last week, Tutko offered this psychological analysis ol Phillies fever:

Sports, teams, Tutko said, give people who aren't big winners in our competitive society "one of the few opportunities they have to feel really good about themselves."

"Our society says you have to be a winner in some ways, but most of us are losers," he said. "By that I mean we have rather mundane or menial jobs with no feedback that makes us feel worthwhile. People who tar roofs, dig ditches, pump gas don't get much reward except a monetary one, and people need more self-fulfillment than that."

Identifying with a sports team is one way to get it, Tutko believes. Even a team that wins only 62 games out of 162 has provided 62 opportunities for people to feel good. "People get tremendously excited when their team wins because their identity is there. People don't say, 'The Phillies won. The Phillies beat Kansas City.' They say, 'We won. We beat them,' and they are part of this 'we.'"

Tutko believes that sports teams have become a major source of identification in most big cities because television and the other media provide so much information about players and their lives and because other sources of identification – like neighborhoods – are less potent now that people are more mobile.

This is especially true in Philadelphia, where the status of the city has been closely tied with the performance of its sports teams, particularly the Phillies. As long as the Phillies were losing, they helped perpetuated the stereotype of Philadelphia as a loser city, the brunt of all those bad jokes about how many weeks you'd have to suffer here if you won second prize.

Having a team that wins a major sports event like the World Series or Super Bowl is a way of establishing the supremacy of the city. "We're getting to the point where these events are much like the World Cup soccer matches in Europe, where countries complete against each other and there's a lot of nationalism involved. It's like the country of Philadelphia defeated the country of Kansas City, so it's a better, stronger city."

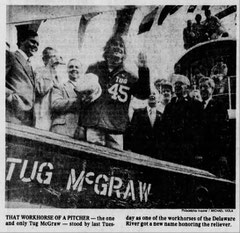

Tutko said Tug McGraw perfectly expressed this sense of supremacy when he said, at the victory rally on Wednesday, that "all through baseball history, Philadelphia has had to take a back seat to New York City. Well, New York can take this world championship and stick it, 'cause ; we're Number One!" McGraw was psychologically correct in bringing up New York rather than Kansas City, because it is New York that Philadelphia has been negatively compared with on more accounts than baseball – like art, culture and so on.

The close Identification that Philadelphians feel with their team explains, Tutko said, the boos some Phillies team members got in September when they were in a slump and the team was losing. "Nobody likes to accept weakness and failure. When a team member is doing badly, you punish them for the frustrations and failures you feel in your own life," he said.

It also explains why, for some " drunk and overexuberant fans, the joy turned to anger early in the morning after the Phillies victory and fights broke out on the streets, Tutko said.

"Sometimes a frustration emerges " that I call post-victory depression. People have expended so much effort and time and pain, so much is involved and all of a sudden, it's over and people feel empty. It's the attaining of the victory, not the victory itself that is the joy, and some people get depressed because they start to realize that tomorrow they'll have to go back to living their real lives," Tutko said.

The psychologist said that the real psychological problems will begin next year, when the Phillies – and, vicariously through them, the fans, and the city – have to prove themselves again.

‘I want to play’

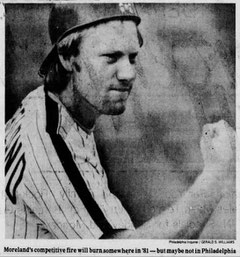

Boone’s in, Moreland wants out

By Frank Dolson, Inquirer Sports Editor

Keith Moreland was riding a cloud through the stretch drive of the pennant race, through that unforgettable week of the playoffs, and finally through the World Series. "I've never been through anything that exciting," he said.

It's hard to imagine anybody who plays harder, who roots harder, who wants to win more than this former University of Texas football player who has been hitting line drives, getting base hits ever since arriving in Philadelphia in September of 1979. Moreland squeezed every ounce of excitement and joy out of being a part of the World Series, out of riding down Broad Street in the victory parade, out of standing on that platform in the center of JFK Stadium and hearing the cheers, seeing the smiles of the huge crowd that turned out to salute the Phillies.

That was Keith Moreland's idea of heaven. He's an emotional young man, a guy who has no trouble getting psyched up for a game – whether it's against Oklahoma in the Cotton Bowl or against Kansas City in the Vet – and no aversion to letting his feelings show.

"There's no question," he said shortly before heading back to his Texas home, "this was a great year, a perfect year. I saw the team progress... I saw the team pull together. I got to sit back and watch a great catcher (Bob Boone) for a year, watch how he handles pitchers and handles the' game. I got to see three (future) Hall. of Famers perform in Pete Rose, Steve Carlton and Mike Schmidt."

It was all so wonderful that it string catcher was struggling at had to be exceedingly difficult for Keith Moreland to talk what was on his mind: the desire to play every day in 1981 instead of just once in a while, even if it meant playing for another team.

Watching others play has never been easy for Moreland. Yet he never griped about his part-time role, never told the press – or anybody else – that he should have been playing ahead of Boone when the Phillies’ first-string catcher was struggling at the plate and getting booed by the Vet Stadium crowd.

"I just like to win," he said.'- "That's the reason I never said anything during the season about playing. I would never be a bitcher and a moaner."

But he does want to get more than the 159 at-bats he got this year. He does . the opportunity to become an everyday ballplayer. And. he does not expect that opportunity to come in Philadelphia.

"I want to play somewhere," he said. "I have nothing derogatory to say about the Philadelphia Phillies. The men on the ball club are outstanding individuals. The coaching staff works with you tremendously. The front office – all the way from the owner, the general manager, everybody – it's an outstanding organization, the best in baseball."

Still, as good as it is, Keith Moreland plans to sit down and tell the Phillies that he would rather be traded this winter than spend another summer watching Bob Boone catch.

"Bobby had an off year and he still did a great job behind the plate, still drove in big runs for us," he said, "and next year he's going to hit .280 (instead of .229) and he's going to drive in even more runs, and he's going to be the same behind the plate. He played through a lot this year – with pain and injury that most people wouldn't have been able to play with. He's got great courage, and next year he'll be healthy and his knees will be stronger and his body will be stronger from the beginning. So the best way I can help my career is to be somewhere else....

"I'm not saying – no, I am saying that Bob Boone's a better catcher, a better ballplayer than I am. So I can just see the writing on the wall. But I want to play. I'm going to be 27 years old next year and I think I proved this year that I can swing the bat, that I'm capable of playing every day and doing a good job for somebody....

"If I could stay here my whole career and play, I would be elated. This is what I've always wanted to do. But you can't make any money and get your family set up and have a future built up for yourself unless you play. And being on this team you've got to think about it, you've got to ask yourself, 'Where are you going to play? Where are you going to play?'"

And the answer keeps coming up the same: behind Bob Boone, behind a man who, despite all those injuries, played a vital role in the Phillies championship drive.

"I learned a lot during the year," Moreland said. "I learned how to keep your mouth shut when you're supposed to keep your mouth shut."

But now the season is over, the, championship has been won. It's time for Keith Moreland to think about himself.

"You know," he said, "playing baseball is easy. It's something that's come easy all my life. It's fun. That's why I want to play – because it is so much fun. But when you're watching all the time and wanting to be in there all the time...."

Then, sooner or later, the fun is drained away.

That didn't happen this year. It was all too new, all too exciting – from the first day of spring training to the post-World Series parade. But in a profession where the years fly by so quickly, a young man with Moreland's ability has to took ahead. Even in the afterglow of Wednesday's parade, he never lost sight of that.

"You looked like you were having the time of your life," a friend told him when the parade ended.

The No. 2 catcher on the world champion Phillies nodded. 'It was fun," he said. "I hope I'm doing the same thing somewhere else at this time next year."

I’d rather be in Philadelphia, home of champs

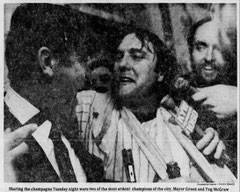

Cradle of liberty sounds nice,' and City of Brotherly Love is nice too, but Home of Champions rings with verve. What does a World Series mean to a city? As Tug McGraw says, it "goes down smooth and warms you all over."

By Bill Lyon, Inquirer Staff Writer

So what's it worth, being a World Champion?

After the champagne shampoos, after the parade, after all the chesty braying, the obligatory "We're Number One" screeches, the sea of brandished index fingers, what does having the best baseball team on the continent mean to a city?

Can 25 men in form-fitting double knits, hitting a round ball with a round stick of wood, in one October night undo all the damage of that scathing civic slur by a bulbous-nosed comedian?

Is W.C. Fields watching? Does he take it back? Is he contrite now? On the whole, would he rather be in Veterans Stadium, strung out on Phillies Fever?

It isn't negotiable, a World Series. That gleaming trophy won't bring that much in a pawn shop. The championship may atone for 97 years of frustration and futility, but it won't make the subways safer, it won't fill in the potholes, it won't lower the price of gas, it won't free the hostages in Iran.

So what, beyond the obvious civic pride, is it worth?

Reputation. Fame. The way a city is perceived by those who do not live in it.

As we shall examine in this essay, for some towns, like Oakland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and, yes, even New York, there has been nothing especially rewarding or enduring about a championship. For others, notably Pittsburgh, winning brought a remarkable conversion; a frog became an alluring prince.

It would be naive and unrealistic to assume that just because the Phillies won the World Series, Philadelphia's image will now be magically transformed.

It doesn't work that way. But it is a start. And there is this suspicion that, given the American public's penchant of rooting for the underdog, a lot of the country was pulling for the Phillies. In a perverse way, they may have identified with the years of failure, and as a consequence, rejoiced when deliverance was at hand at last.

Philadelphia won? The Rodney Dangerfield of cities finally gets some respect. Take heart, Cleveland. Your turn is coming, Buffalo.

It is suspected that Tug McGraw echoed a common sentiment when he punctuated the victory parade with his now-famous declaration: "New York can take this world championship and stick it, 'cause we're Number One!" It is a uniquely American viewpoint, the celebration of long-sought vindication, the rare confirmation that, every once in a while, the underdog has his day.

New York has had the World Series.. Too many times to suit most people. New York doesnt need a world champion. It has everything else, anyway (including, it might be peevishly added, bankruptcy).

It is interesting that the only time anyone outside of New York rooted, for that metropolis was when the Mets were in the World Series, because the Mets seemed so un-New York, so hapless, so zany, so charmingly inept, so bumbling but so persevering. So human. So, uh, well, Philadelphian.

•

A world championship is not an automatic blemish remover. Oakland Won the World Series for three straight years less than a decade ago, and not many remember outside of baseball purists. And that city didn't become a mecca for tourism. There was no stampede by conglomerates to shift their corporate headquarters. "Oakland remains upstaged by its more glamorous metropolitan neighbor across the bay. The Oakland A's, three-times-straight ' world champions, and they didn't change the title of the song to "I Left My Heart in Oakland."

Cincinnati won a World Series, too, and the general reaction by the rest or the country was, yawn, that's nice, a small parochial, provincial village gets its day in the sun; hurray for middle America and all that, Cincinnati needs it; after all, what else have they got?

Los Angeles? Home of the transplanted Dodgers? Sure, but a World Series didn't get rid of the smog, did it? It didn't bring order to that chaos they call the freeway system, did it? Even in LA itself, the victory parade gets upstaged by that more-famous cry, "Surfs up!"

Only two cities seem to have made a world championship work for them. Green Bay and Pittsburgh.

Green Bay with professional football. The Packers. Vince Lombardi and Title Town, USA. And now even that seems so long ago, a faded tintype, curling around the edges, faded, frayed. "The Pack Is Back" has a hollow, mocking ring to it. Even world championship shine loses its luster if it is not periodically repeated. Our memories are notoriously short.

Which leaves Pittsburgh. For those who hope that a title will change Philadelphia's image, Pittsburgh offers the most promise. For this is Philadelphia's country cousin who made it big.

Once, like Philadelphia, it was the butt of cruel civic barbs. "Hell, with the lid off," they called it. Pittsburgh was best known for its soot. The Paris of Pollution. The Athens of Ashes. Hard hat town. Mill town. Tough town. Blue-collar town. Shot-and-a-beer for breakfast. Know how to tell the bride and groom at a Pittsburgh wedding? They're the ones wearing the pressed bowling shirts. Yuk-yuk.

But then the Steelers won the Su; per Bowl. And then they won it again. And again. And yet one more time. And the Pirates won the World Series. Two world champions in the same giddy year, and now all the civic characteristics that had drawn the slurs somehow became a source of strength and pride instead.

They romanticized about Pittsburgh, its brawling toughness, its stoic endurance. Two professional sports teams did for Pittsburgh what the poet, Carl Sandburg, had done for Chicago. Pittsburgh... Steel City. It has a ring to it, like a hammer on an anvil, bespeaking strength and in-domitability and permanence. Forget the slag heaps; look at those blast furnaces, those open hearths... look at the fires, the sparks, the power.

The ultimate compliment comes when travelers fly into Pittsburgh. The pilot, silent until now, announces simply, "On your right is Three Rivers Stadium, home of the Steelers and the Pirates. Welcome to Pittsburgh, City of Champions."

It is enough to make the Chamber of Commerce positively swoon.

Listen to the mayor of Pittsburgh, Richard Caliguiri, in an interview last January after the Super Bowl banner was hoisted alongside the World Series flag:

"We've never been able to get people to visit Pittsburgh, but the City of Champions is giving us the favorable exposure we need. Last year I got 400 mayors to come here and they left as 400 ambassadors for Pittsburgh. The City of Champions is a common denominator; we're all caught up in this. It makes it easier for me to sell my program. We had the cake built, but the Steelers and the Pirates are the icing on the cake.

"What I am saying is that if the teams don't continue to win, and that sometimes happens, the city is still here. We want to be a City of Champions as a city, not just in sports."

But it is sports that draws the initial attention, and Philadelphia is on a hot streak now, an unprecedented roll. In the last three championship finals of major pro sports, Philadelphia has been represented – the Flyers in the Stanley Cup, the 76ers in the NBA finals, the Phillies in the World Series. And now the Super Bowl is just three months away, and the Philadelphia Eagles already are 6-and-1 and... well, Cradle of Liberty sounds nice, and City of Brotherly Love everyone knows, but Home of Champions?

"Sounds nice, huh?" asked Tug McGraw, contemplating a winter in front of the fireplace with a jug of Irish whisky. "It goes down smooth and warms you all over.

"And I don't mean," he added, grinning, "the whisky."