Philadelphia Daily News - Hallelujah Insert - Oct. 23, 1980

One to Remember

By Tom Cushman

On an afternoon in the early fall of 1946, at a grade school in a small Missouri town, the door to a classroom opened and in walked a messenger from the principal’s office. Moving across the floor about as quickly as any turtle you’ve ever seen, he eventually arrived at the blackboard, where he added the final numbers to a linescore which had been drawn in chalk and positioned directly beneath the next day’s history assignments.

The Cardinals got a “1” in the bottom of the eighth, the Red Sox a “0” in the top of the ninth, meaning that St. Louis had won the seventh game of the World Series, 4-3. Class was dismissed.

It was late that afternoon before I learned that Country Slaughter had carried home the winning run, scoring on a hit by Harry “The Hat” Walker while shortstop Johnny Pesky of the favored Red Sox – a bunch of swells who had been nicknamed “The Millionaires” – paused momentarily with the relay. Pesky never came to understand why a man would attempt to go from first to home on a single, but Pete Rose does.

The town in which I lived back then was perhaps 100 miles from St. Louis, and none of the kids I knew had ever attended a major league baseball game. During the war years, which had just ended, if you had any kind of automobile at all there was no gas and you could expect maybe three flat tires driving to the grocery store. Most of our fathers had been gone anyhow.

None of us had even seen a major league player except in newspaper pictures and these were never on the front pages, which were reserved for Dwight Eisenhower, Douglas MacArthur and Harry Truman.

I don’t know if Harry called Eddie Dyer, the manager of the Cardinals, to congratulate him that afternoon, but I doubt it. Harry was from Missouri, but he favored poker over baseball.

Still, the day remains as one of several islands which float occasionally through the memory, in sharp detail, glistening in the sunlight. I remember that day as being cool, because we wore jackets as we stood in the schoolyard discussing Country Slaughter, and Stan Musial, and Harry “The Cat” Breechen. I also recall feeling very good for some reason I couldn’t understand then, and still can’t.

•

My friend Eddie Chambers, who pours fine drinks at the Grand Coach Restaurant over in Jersey, thinks he was 10 years old when he attended his first Phillies game. He knows it was in the early ‘30s, and that it was at the Baker Bowl, and- even though I forgot to ask- he would remember the score.

Eddie has gone with the Phillies ever since, and it has not been an easy ride. He has handled it well, throwing things only at home and never in his place of business. He insists to this hour that the only Philadelphia player he ever booed was Richie Allen.

Eddie looks drawn on the days after a game rolls through somebody’s legs, and his step is lighter when the Phillies win. He had a dream once, he told me several years ago, that they would win it all while he was still on this planet.

Eddie and his wife Helen had planned to use part of his vacation this year to take a cruise. If you’ve checked the price of cruises lately, you’ll understand why they didn’t.

Helen suggested a trip to Mexico as an alternative. “Pick the date,” said Eddie, “and we’ll go.”

Helen signed on for the week of October 13. The significance of this did not really close in on her husband until the Phillies began winning games from the Pirates in September. You will understand why this is a strong marriage when you realize that no one was injured in the discussions which must have followed.

“Do you think that the Series might be on television in Mexico?” is the only question Eddie ever raised to me, while discussing his problem.

He watched them in Mexico City, he watched them in Taxco, he watched them in Acapulco. “The Sunday game in Acapulco was the best,” he was saying the other day. “They had a room with a wide-screen TV. The waiters wore baseball caps. They served beer and hot dogs. The commentary was in Spanish, but I know some of the language. I understood them every time they said ‘Pete Rose.’”

Eddie and Helen returned to Philadelphia late Monday, and Eddie was at the ballpark while history was being written on Tuesday. Knowing that he wanted very much to be here when his team closed the show, I asked him how he handled it after the Phillies had gone up, 2-0. Did he pray for a couple of Kansas City victories so that he and the tournament would return to Philly at approximately the same hour?

“No,” Eddie Chambers replied. “I prayed for rain.”

•

As we were busy growing up in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, my sister, Joyce, approved of Cardinals only if they nested in the backyard. Maybe she would have been interested in Stan Musial if he had been in geography class, had wheels and asked for her phone number.

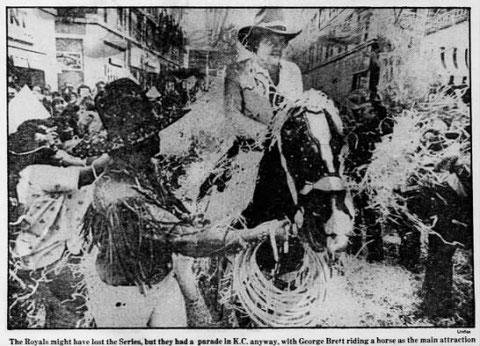

Now fortyish, and a resident of Kansas City, she admits to being somewhat addled when the Royals are the subject. A long-time member of the Kansas City school board- where the battles are reminiscent of the trench skirmishes of World War I, wife of a Presbyterian minister, mother of two daughters, she thinks George Brett has a lovely swing.

So do both the young ladies, who went directly from church to Royals Stadium on Sunday, as were excused from school yesterday so they could join in the ticker-tape parade proffered the baseball team on its withdrawal from the wastelands of the East.

George Brett rode through the city on a horse. “I followed along to a point where there was sort of a break in the crowd, then I ran up and he shook my hand,” said Margaret, the elder of the nieces, who until yesterday had always had a reputation for washing both hands before dinner.

One thing which should be pointed out here, the parade in Kansas City was set, win or lose. The one scheduled for Philadelphia included an asterisk.

For one who assumed- because I had pictures of him in my room- that Marty Marion was a classmate, my sister has come a considerable distance. She has this thing for the Royals, yet when they played portions of Tuesday’s final game like hemorrhoids are contagious, neither she or the town came unglued.

“Probably the best way to explain the attitude here is that beating the Yankees was the ultimate for us,” she was saying last evening. “I don’t think people who saw the World Series saw our real team. They’re a laid-back group, but they had been consistent before.

“I sense disappointment, but not ill feeling. The town is close to these guys… we have a Frank White, who went to Central High School here, and George Brett, who has become a dynamic member of the community. I think there were some of the Philadelphia players that we didn’t care for, but there also was a feeling for the Phillies as a team. They were underdogs like we’ve been, and we admired the way they battled. There is not the kind of bitter feeling there would have been if it had been the Yankees. God, we hate the Yankees.

•

Each of these items, as recorded here, helps in its own way to bring this season into some kind of personal perspective. Watching the events of the last weeks, and the community catharsis of the last several hours, there can be no other judgment than positive.

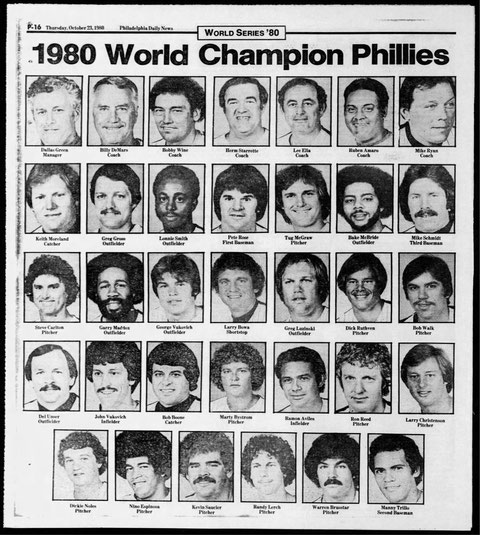

I particularly enjoyed watching Mike Schmidt grow into a viable national hero, his performance both on and off the field being of superstar quality in every one of these difficult days.

What a grand stage it was for Del Unser, and when will anyone deserve a spotlight more. To Tug McGraw, John Vukovich, and a few others, we are indebted for making it fun while reminding us, all along the way, that the house payments will have to be made eventually.

I feel good because the people of the city – like the team which represented them – showed a touch of class when the moment was upon them.

And, above all, I loved Pete Rose’s bunt. My sister in Kansas City won’t understand that logic, but – wherever he happens to be – Country Slaughter will.

How the Loud Guy Finally Won

By Bill Conlin

All winter they told Dallas Green how badly they wanted to win.

They told him in the weight room at the Vet, where the manager joined players living in the area for off-season workouts.

They told him during the Phillies Caravan how much they wanted to atone for the playoff failures of 1976, ’77 and ’78, for the collapse of ’79 which had brought Green down among them.

Green filed it all away. He would see in due time whether they were more interested in batting practice or making a four no-trump contract, whether the extra men wanted the numbing chill of an April night on the bench yelling for the regulars more than they wanted a steaming cup of coffee in the Players Lounge.

He’d find out if they wanted it badly enough to sacrifice batting averages for team winning percentage, badly enough to take the extra base, obey a take sign in the middle of an 0-for-15 slump with the count 3-1. He wondered if they had the desire and discipline to move a runner from second to third with a ground ball to the right side.

Soon, it would be March and he would start finding out.

•

Wednesday morning, March 5, the first full-squad workout of spring training… It is usually a day filled with optimism, even for clubs without a chance of contending. But on this morning, there is snickering in the clubhouse, cynical asides. There is a huge white sign with red lettering next to the entrance to the Carpenter Complex clubhouse. It is strategically located so that anybody stopping for coffee, hot soup or Gatorade must look it right in the foot-high block letters.

It says, “We, Not I!”

Larry Bowa sneers. “Christ,” the shortstop says, “what time do the bleeping pom-pom girls come in to lead the cheers?”

•

That was the attitude. They told Dallas Green how badly they wanted to win. But they still wanted to do it on their terms, not his. They didn’t want spring training to interfere with their golf or tennis games, with their beach time or cookout time.

As spring training flowed into the regular season, he spelled out the program for them time and time again, always in a growl, shout or undisguised bellow which ruffled their delicate sensibilities. The program was simple:

When you come to the ballpark, come on time. When the team bus arrives at the ballpark when we’re on the road, all card games, dominoes or backgammon will stop. When you come to the ballpark, you’re mine. Everybody takes batting practice, everybody takes infield practice. During the games I want everybody on the bench rooting for the guys in the field, or our guy at bat. I want everybody watching the other team, how they play our hitters, how they defend the bunt, how they throw from the outfield, how they pitch our guys. I want hustle on the field at all times. Phillies baseball. We don’t have a lot of guys who can hit the ball out of the park anymore, so we’ve got to grind it out, make things happen, be aggressive on the bases.

Uh huh, we’ll be right there, Dallas, as soon as we finish this bridge hand. Go on out and watch the extra men hit.

•

United Charter Flight 5004 descends over the gently rolling farmland of Western Missouri. Traveling secretary Eddie Ferenz is busily passing out red and white pom-poms to a group of pretty cheerleaders. The cheerleaders are the wives of the National League Champion Phillies. They will shake them for the photographers when they deplane at Kansas City International Airport. They will shake them with vigor and enthusiasm because their husbands have taken a 2-0 lead in the World Series and they are suddenly involved in the most breathtaking two weeks of their young lives.

A writer who recalled Bowa’s reaction to the “We, Not I” sign in March could not help noticing the ironic parallel. Finally, here were the bleeping pom-pom girls to lead the cheers.

•

Green played the media the way Nijinsky danced Swan Lake. Not that he was that crazy about the milling, probing, often abrasive local sportswriters. In his regard for the press, Dallas is a lot closer to Ruly Carpenter than he is to Frank Luccesi. But he discovered early on that words which rolled like water off ducks’ backs when he spoke them in private to his athletes tended to have much greater impact when they appeared in print. Hackles actually began to rise, which was what Green wanted. Anger, he felt, was infinitely preferable to practiced cool, even when directed at him.

The Green-orchestrated media cannonade directed at the future World Champions became so intense after the Phils had lost a sixth straight game in Cincinnati on Wednesday, July 23, that Greg Luzinski, back home on the disabled list with a surgically-repaired knee, even got into the act. The Bull told a columnist that Green was coming on like he was the “bleeping Gestapo.”

Green told writers that Luzinski was entitled to his opinion, but if he wanted the manager’s job he should go to Ruly Carpenter and apply for it.

All through the Phillies’ frenetic, driving September and October, the air was filled with rancor. And Green’s player relations bottomed after a dramatic, 15-inning comeback victory over the Cubs. That’s the night he said it wouldn’t surprise him if some guys “weren’t rooting for us not to win this thing.” Bowa had ripped Green’s failure to start veterans Bob Boone, Maddox and Luzinski in the crucial series with Chicago on a radio show earlier in the evening. Dallas replied by saying if he ever revealed everything he had on his shortstop, “he’d never play another inning for the Phillies, and that’s official.”

Through all of this, the Phillies were playing the most intense baseball in their history. They were winning. They were following the program, even though it was often with gritted teeth. “They’re finally proving to me and to themselves that they want to win this thing as badly as they’ve been telling me all along they want to win it,” Green said. “They’re doing it my may, which is the way I’ve told them it had to be done. There’s some ruffled feelings out there, but that’s OK. I don’t hold grudges. I hope they don’t either.”

•

It is October 21, Game 6 of the World Series. The extra men and pitchers are lined up along the first base line. Now Dallas Green is introduced. The largest baseball crowd in Vet history, 65,838, roars as Green runs to join them. Not one player applauds.

•

Garry Maddox was talking after the historic, 4-1 victory.

“The manager’s in charge and it was up to us to make the adjustments,” Garry said. “We accepted his program, it paid off and I have to give him a lot of credit for that. Though I might not agree with a lot of things that he did, I have to respect what he did and I have to give him a lot of credit for doing what he thought was right and being successful with that.”

But there was still a bone of contention caught in Garry’s throat.

“He didn’t feel he had to tell us anything he wanted us to do. We would maybe have to read about it or something like that. I think he went to the press before coming to talk to us and I think that rubbed a lot of us the wrong way,” he said. “But that’s just a small thing among many things that happened. When you change managers there are gonna be some guys who won’t go along with him.

“It was hard on me, no question of that. I disagreed and was mad. He took me out a lot of times in situations where I thought he should at least talk to me to try to communicate with me, but didn’t. I wanted to play. I wanted to be a part of this team. That was the way he was gonna run things. He’s the manager, he’s in charge and I had to go along with that if I intended to play. That’s the way it is.”

•

Bill Virdon was named National League Manager of the Year by his peers the other day. Virdon edged Atlanta’s Bobby Cox and Montreal’s Dick Williams in one of the closest elections on record.

Dallas Green didn’t get a call. That’s because he broke too many time-honored lodge rules. He criticized his players publicly. He shafted Randy Lerch and Nino Espinosa. He had the audacity to say in print that anytime you score three runs you should beat the New York Mets. Also, he was a pitcher in a league where the only other ex-pitcher managing is Tommy Lasorda.

It should be pointed out the managers had plenty of time to cast their votes. Ten of them who attended the playoffs had absolutely nothing else to do.

Meanwhile, Dallas Green was occupied with the task of managing baseball games until Oct. 21.

And as Garry Maddox says, that’s the way it is.

That’s Incredible – That’s Baseball

By Stan Hochman

So it wasn’t Willie Mays scampering under Vic Wertz’ fly ball, catching it over one shoulder, cradling it like a baby.

So it wasn’t Sandy Amoros scuttling into the left-field corner at sun-dappled Yankee Stadium. So it wasn’t Billy Martin scooting under an infield pop nobody else wanted… or Bobby Richardson lancing a line drive by Willie McCovey.

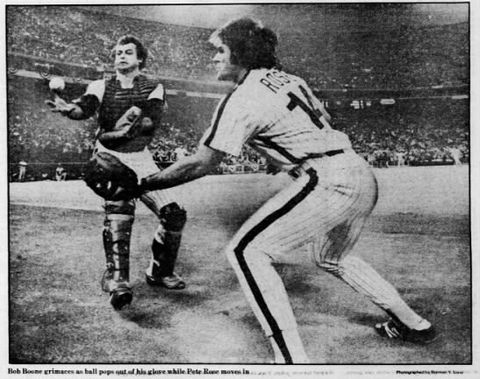

The foul pop squirted out of Bob Boone’s glove like a slick bar of YMCA soap and Pete Rose was there to snag it.

Snagged it before it hit the front edge of a dugout crammed with pop-eyed players and narrow-eyed cops and mean-eyed police dogs.

And if that’s the memorable play to etch the 1980 World Series into the national consciousness, so be it.

Boone gimped after the pop foul in a leg that had never really mended after off-season surgery. On a foot that was swollen and blotchy from a playoff collision.

Rose is 39, ancient for a baseball player, unheard of for a guy who played every nerve-gnawing game of the regular season plus 11 quick-aging post-season episodes.

The Stanford graduate and the high school dropout converging on a ninth-inning foul pop. And somehow, some way, turning it into an out. While the goofy, marionette of a pitcher waggled to cover home plate, just like the book says you should.

That, friends, is baseball.

That, sports fans, is why baseball is the greatest game in the whole half-vast world of fun and games. Round ball, round bat, making the possibilities infinite.

And no clock to run out on a team rallying from what seemed like hopeless, hapless defeat.

The Stanford graduate and the high school dropout and the crazy relief pitcher and the hyper shortstop and the cool third baseman proved it one more time… the joyous drama that is the summer game.

The Phillies turned all those double plays and the Royals couldn’t even get a routine forceout at second base. And that is part of the reason the Phillies won a championship.

But maybe they won it when Larry Bowa stole second base in the first game of the tournament, his team trailing 4-0. Maybe that risky play was the bugler’s call to charge… that indeed, the Phillies would be playing aggressive, emotional baseball. The kind of aggressive, emotional baseball that enabled them to win 21 of their last 28 on the road, to keep scrambling off the canvas with nine guys standing over them, counting.

And maybe they won it when Dallas Green grumbled downstairs with his gravel voice and his gravel disposition.

And maybe they won it years and years ago, when Jack Quinn got fed up with Rick Wise’s modest demands for a raise and swapped Wise to the Cardinals for Steve Carlton.

Carlton has had some gallant seasons for the Phillies, but none like this one. Game after game, throwing pitches that splintered bats and broke hearts.

He won both his World Series starts and he was magnificent Tuesday night, blitzing into the eighth inning with a four-hitter before the fatigue of 331 innings blind-sided him.

It would be nice to know how he felt about his remarkable season, about the incredible playoffs, about the first baseball championship this city has ever known.

He continues to hoard his thoughts. He is beginning to resemble an aborigine tribesman who will not be photographed lest you steal his soul in the camera’s black box.

He must feel something. If that isn’t emotion twitching across his handsome face when he pitches, then someone should check him for Bell’s Palsy.

He showed up at the parade in a white shirt and tie, quixotic to the end.

And if Carlton chooses to bury his emotions deep inside, there is always Tug McGraw, patting his chest after a fluttery moment, pounding his thigh, punching holes in the noisy night sky, striving for records in the standing broad ump.

And then there is Mike Schmidt, who has learned from bitter experience that an overload of adrenalin will jerk his head around like whiplash and turn his palms too damp to grip the bat.

So Schmidt ties to look cool, hoping he can fool his adrenal glands, thus keeping his chin tucked in and his palms dry.

It works. Lord, how it works. The man hit 48 homers and made Gold Glove plays in the field. Has there ever been anyone who has ever played this wonderful game with that much power and that gifted a glove?

Now the world knows. And more important, maybe Mike Schmidt knows too, just how good he really is.

And for all the splendid things that Bowa and Manny Trillo did in the middle, and for all the key hits Bake McBride rapped and all the balls Garry Maddox caught and for all the intangibles Rose brought to the tournament, the Phillies would not have won it without the extra guys.

Fred Shero once said that if you don’t use your bench, ultimately it will kill you. Dallas Green used his bench.

Used it that last week of the season despite Bowa’s harangue. Got Del Unser enough action to thaw out his stroke. And when Green summoned Unser in the World Series, he summoned a sharp, confident pinch-hitter.

Give Green credit for using the youngsters like Bob Walk and Marty Bystrom in situations they could handle. Give him credit for squelching that infamous almost-trade of Lonnie Smith for Billy Smith.

Give Paul Owens praise for the trades he did make, for bringing back Dick Ruthven, for swapping John Stearns for McGraw, for rescuing Unser from a free-agent scrap heap.

Green kept them involved, kept them motivated. And used them when all those games clattered into extra innings.

“You win ‘em late,” Schmidt pointed out, “and that means it’s guys coming off the bench who are doing it. Pinch-hitters, relief pitchers.”

Don’t blame them if they cherish the moment, roll the taste of it around like fine burgundy. There is no way all 25 of them will be back to defend the championship.

That’s baseball, too.

The Phillies have a decision to make on McGraw, who would prefer to stay put, rather than test the cash-green waters of free agency.

Do they trade one of their moody trio of outfielders? Who goes to Texas in exchange for Sparky Lyle? Sign Larry Christenson or lose him to free agency?

Can the guys who do return survive another summer of Green’s whip-cracking, finger-pointing monologues? But all that can wait.

“Savor this,” Schmidt advised the JFK Stadium mob yesterday.

It is something to savor, even if the only thing you remember is the ball squirting out of Boone’s glove and into Rose’s grasp. Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. John Keats would have loved baseball.

Here’s To The Winners – The Fans

By Ray Didinger

I was watching the Phillies celebrate their first world championship, watching them scurry around the clubhouse wielding their champagne bottles like fire hoses and, all the while, I kept thinking about my grandfather.

That’s right, my grandfather. As far as I was concerned, he was the real hero on Tuesday night. He didn’t get any champagne and he didn’t get on television but he sat there in Section 212, Row 18, and he savored the final out in a way Mike Schmidt and Larry Bowa never could.

I heard Larry Bowa say he waited “a long time” for this moment. Actually, he had waited 11 years, that’s how long he’s been picking up ground balls with the Phillies.

The way I figure it, my grandfather had waited 60 years, most of them longer and grimmer than a Depression bread line.

My grandfather strapped his heart to the Philadelphia Phillies way back in the 1920s and, after six decades, all he had to show for it was a pacemaker and a TV chair with a busted arm.

You see, every time the Phillies did something stupid- which was often- my grandfather would bang his fist on the arm of his chair. You didn’t even have to be in the same room with him to know how the game was going.

Bang. Uh oh, Joe Koppe must’ve struck out again. Bang. Pancho Herrera must have dropped another popup. Bang, bang. Mauch must be coming out of the dugout.

My grandfather and his chair have been through a half-dozen National League pennant chases and, frankly, neither one will ever be the same.

When the Phillies went into their September death spiral in 1964, my grandfather sat there, shouting and banging through every defeat.

I remember sitting with him one Saturday afternoon during that horrid losing streak, watching the Phillies blow a six-run lead against the Milwaukee Braves.

I remember Rico Carty triple off the Ballentine scoreboard to win it and, for the fist time all day, my grandfather didn’t bang on his chair.

He just sat there, staring silently at the TV set. I kept waiting for him to say, “Ahh, we’ll get ‘em tomorrow.” He had said that all along. This time, he didn’t say anything. He just reached over and flicked off the television.

That’s when I knew it was all over for the ’64 Phillies.

My grandfather already had his tickets for the World Series opener at Connie Mack Stadium. He could have taken them back for a refund but he never did. He just kept them in his desk drawer.

He never said so but I always suspected he thought that was as close as the Phillies were ever going to come to a world championship. He just kept those worthless tickets around as a bittersweet remembrance, like rose petals from a summer romance that almost, but didn’t quite, work out.

That’s why I know how much Tuesday’s World Series triumph meant to him. It was his chance to reach out and embrace the moment he had waited for, the moments his Whiz Kids had promised but never delivered.

I’m not writing this just for my grandfather, but for all the people in this baseball-happy town, all the people who have made the long, painful journey from the Baker Bowl to Shibe Park to Veterans Stadium and never lost the faith.

Phillies fans lived on canned beans and stale bread for half a century. They rooted for a team that had seemingly made a pact with last place, yet they sat on their stoops with their transistor radios pressed to their ears and they rooted just the same.

Those are the people I felt he happiest for on Tuesday night. All the people who wept in the stands, the people who danced and sang in the streets. This win belonged to them as much as it did to the mercenaries in pinstripes, maybe even more.

•

My grandfather’s name is Ray Didinger and if you ever worked up a thirst driving through Southwest Florida, chances are, you’ve made his acquaintance.

He owned a bar on Woodland Avenue for 30 years. He named it “Ray’s Tavern” which should tell you something about his outlook on life. He is a straightforward man, an unpretentious man who never used a neon sign when a hand-lettered one would do.

“Ray’s” was a sportsman’s bar, which is to say it was not the place where you went to listen to the jukebox or sing opera. Anyone who tried to punch up a Frankie Laine record when the Phillies were on TV usually wound up being heaved onto Simpson Street by several burly regulars.

“Ray’s” was a place for guys who loved sports. If you wanted to discuss politics, go to the Union League. If you wanted tips on the stock market, go to the Warwick. But, if you wanted to know what pitch Del Ennis hit in the ninth last night, Ray’s was the place.

Ballplayers, umpires and just plain folks hung out there, drinking beer and trading sports stories. My grandfather worked behind the bar almost all the time, except when he’d toss his apron over his shoulder and head off to the ballpark.

If there was a bigger fan in this city, I’ve never met him. My grandfather is the only man I know who actually went to see the old Frankford Yellow Jackets play football. He talks about seeing Red Grange play the way most people talk about seeing O.J. Simpson.

He ran chartered buses from his bar to all the Eagles’ home games for almost 20 years. Most of his customers bought their Eagles season tickets through him. Maybe 400 of them.

My grandfather put out the money for the tickets. Once in a while, the guys even paid him back. My grandmother would get mad and tell him to get tough with the guys who owed him money.

My grandfather would say, “OK,” and he’d walk away, puffing on his cigar. The next thing you know, he’d be loaning somebody $20 and telling him not to worry about it. That’s just the way he is.

He loves all sports but baseball is his passion. Every March, he and my grandmother used to pack up their belongings and drive to Florida to watch the Phillies train in Clearwater.

They would return a month later, sun-tanned and optimistic, more convinced than ever that the Phillies would win the National League pennant. Their tans lasted the summer, but their optimism usually faded in June.

Every spring, my grandfather would discover one young player who was sure to turn the Phillies around. Bob Bowman was one such “can’t miss” prospect. Ron Stone was another. I don’t think either one ever got a hit north of Jacksonville.

One year my grandfather came back raving about a kid pitcher named Ferguson Jenkins. He said this Jenkins could be a 20-game winner. He was right, except Jenkins was traded and won his 20 games for the Chicago Cubs. My grandfather never forgave Gene Mauch for that one.

My grandfather is a typical Philadelphia fan in that he likes players who get their uniforms dirty, guys with modest ability who get the job done with hustle and desire.

He loved Cookie Rojas and Tony Taylor, for example. He likes Pete Rose, even though he has trouble justifying his salary. He can’t understand how Pete Rose can earn more in one season than Ty Cobb earned in a lifetime.

I try to argue the case from the standpoint of 1980 economics and the impact of the free agent market. Then my grandfather says, “Yeah, but I saw Ty Cobb and he was the greatest player who ever lived,” and I realize I’m whipped.

To my grandfather, baseball is not a matter of economics, it is an affair of the heart. He roots for the Phillies because it’s the one constant in his life. It’s the one thing in this world that isn’t spinning out of control.

He can live with the OPEC oil ministers and the Abscam tapes and all the rest, just so long as he knows Tug McGraw is down in the bullpen and Mike Schmidt is waiting in the on-deck circle.

For years, the Phillies let him down, some years more cruelly than others. But, on Tuesday night, they paid him back. They climbed to the top of the baseball world and they brought him with them.

As I watched fuzzy-cheeked kids like Keith Moreland and Bob Walk revel in their triumph, I could only think of what my grandfather had said earlier that afternoon.

“I hope they win it this year,” he said. “I’m 80 years old. I don’t know how many more chances I’m gonna get.”

Well, they won this one for you, Granddad. They won it for you and all the guys at Ray’s tavern who hung on by their fingernails waiting for this day.

This is your moment. Enjoy.

Game 1: Using Walk in Opener Paid Dividend For Phils

By Rich Hoffmann

With a cattle prod for a voice and a bench full of hungry kids, Manager Dallas Green somehow cajoled the Phillies to the 1980 National League pennant, their first since 1950.

So, it was somewhat fitting that Green chose to start Bob Walk – rookie Bob Walk – in that World Series opener at Veterans Stadium, the first in Philadelphia since Jim Konstanty lost to the New York Yankees during Harry Truman’s sixth year as an unpopular President.

And perhaps it was even more appropriate that Walk and the Phillies won, 7-6 over the Kansas City Royals.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Bob Walk obviously was not Dallas Green’s first choice to start the opener; the fact that Walk was the only pitcher on the staff Green did not use in the playoff series against Houston tells you that.

It also tells you why Walk started Game 1. He was the only fresh arm available. The five games against Houston had been brutal – the last four went extra innings, and Green used six pitchers each in the victories in Games 4 and 5. Playing Dallas Green’s brand of grind-it-out, character baseball can be a draining experience, especially when the whole season is on the line. The starters were spent, the bullpen was rag-armed, and Walk was getting the ball in Game 1.

Walk started the season with an 8-1 record and finished at 11-7. His ERA was 4.56 and he had a tendency to… uh… walk… a lot of people. And when the manager said, “I have no qualms about putting him out there, he’s got good enough stuff to beat any team,” more than a few eyebrows were raised.

And then the game started, and when K.C.’s Amos Otis hit a two-run homer in the second inning, and Willie Mays Aikens hit a two-run homer in the third inning, the groans at the Vet became audible.

The only thing that saved Walk was the designated hitter rule, used in even-year Series. When Larry Bowa reached base out of the eighth spot in the lineup, regular-season strategy dictated hitting for the pitcher when behind 4-0. But with Bob Boone hitting ninth instead of the pitcher, Walk was saved and so were the overworked legions of the late and not-so-late innings.

“Going to that bullpen would have hurt us that early in all probability,” Green said. “But I probably would have done it if Walk was the hitter. He had good stuff and as we’ve seen him do in the past, once he got over that early hump, he gave us a good three-four innings.

And the Phillies gave Walk three – four – make that seven – runs. Five of them came in the third. After that Bowa single, he stole second on his own. Now, this was the World Series, and the Phils were four runs behind, and stealing wasn’t the by-the-book move, but Larry Bowa went anyway and made it. The message was clear: These were not the roll-over-and-die Phillies of the recent, gloryless past.

“When Bo stole,” Green said, “It told Kansas City we were not gonna sit back on our duffs and watch the game go by.”

Bob Boone followed Bowa with an RBI double, and Lonnie Smith singles to make it 2-0, only to get thrown out in a rundown play. Pete Rose defiantly refused to back away from a Dennis Leonard fastball and got hit on the leg, and Mike Schmidt walked.

First and second, one out, Bake McBride at the plate. He was 0-5 in the pennant clincher at Houston and worked on his swing mechanics before the Series. The payoff was an enormous, three-run job to right that gave the Phillies a 5-4 lead, wiping out the deficit for good.

“I’m no home-run hitter,” McBride said. “I’m strong, so if I get the right kind of pitch and the right part of the bat, it’ll go.”

The Phils got two more runs – one in the fifth on another RBI double by Bob Boone and one in the sixth on a Garry Maddox sacrifice fly. As it turns out, they needed ‘em both.

Willie Mays Aikens (on his birthday, no less) hit another two-run homer in the top of the eighth, and reporters had a good time asking him whom he was named after.

“The first one, it hit good,” Aikens said, “but I kind of skied it. I was surprised to see it go out. The second one I hit better, but a little bit off the end of the bat.”

Still, it was enough to get Walk out of the game. But Green and everyone concerned had to be pleased – the Phils had gotten seven innings out of the kid. They weren’t necessarily pretty, but they gave the bullpen some much needed time to recuperate.

With Walk’s exit, somebody had to come in and hang on to the led. The logical person was Tug McGraw, the September Flash who led the team with 20 saves and a 1.47 ERA in the regular season. But Tug had worked in all five playoff games in Houston. Surely he needed a day of rest.

Nope. In he came, nailing down the win with two strong innings of relief work.

“What it comes down to, simply, is the ability to do what you’re paid to do,” he said. “The catcher has to throw the ball every day, so do the shortstops. What’s so different about me throwing it?”

Tug was asked if his secret was his mental preparation.

“If that was true,” McGraw said, “I’d be down in the trainer’s room soaking my head in ice. I’ve never been paid a dime for my brains yet.”

Winning always does make the funny lines sound a little bit funnier. It also takes off a lot of the pressure.

“We’ve been through a very nice kind of hell the last 10 days,” Green said. “We’ve played the types of games that have prepared us for any eventuality. Tonight was a piece of cake compared to some we’ve played before. It’s the first game we’ve played in some time where if we lost it out backs wouldn’t be against the wall.”

But as things stood, the future was looking strangely bright. The Phils had not only survived the opener starting a rookie, but they’d won it. The bullpen, except for McGraw, got the crucial day of rest it needed, and now the pitching was all lined up, with mighty Steve Carlton set to go in Game 2 the following night.

And three hour earlier, no one expected any of it.

Game 2: Carlton Not Slick, But K.C. Falls Behind

By Rich Hoffmann

There are always a myriad of stories at a World Series, and Game 2 at the Vet supplied its share.

There was the story of the sure thing that wasn’t, of Steve Carlton, the machine who sputtered, and Dan Quisenberry, the fireman who got burned.

There was the story of Mike Schmidt, the superstar scorned, who finally came through in the clutch. And ultimately, Game 2 was the story of a 6-4 Phillies victory that gave them a 2-0 Series lead over Kansas City.

Nevertheless, the Game 2 story that will be remembered longest was the story of George Brett and his hemorrhoids. His was a case so bad that poor George had to retire to the bench, or at least the dugout, after grimacing through five painful innings.

What with all the excitement, champagne and rich food accompanying the clinching of a pennant, it’s a wonder more players don’t get ‘em.

“Look, it’s a horsebleep subject,” Brett said. “It’s a pain in the ass. I’ve never had such discomfort.”

More medical bulletins later.

After rookie Bob Walk’s unexpected win in Game 1, the Phils sent out the quintessential ace, Steve Carlton, for Game 2. Over the regular season, Carlton was at times unhittable and usually unbeatable, finishing with a 24-9 record, a 2.34 ERA and 286 strikeouts.

“I’ve never faced him,” said Royals rightfielder Clint Hurdle before the game, “but when you call a pitcher ‘Lefty’ and everybody in both leagues knows who you’re talking about, then the guy must be pretty good.”

By all rational standards, this one should have been a breeze for the Phils, or as much of a breeze as a World Series game can be. But on that cool, damp Oct. 15th night, Lefty labored.

He complained for much of the night that the baseballs were abnormally slick, and it showed.

The Royals did everything they could in the batter’s box to foul up Carlton’s rhythm and break his renowned concentration, and it seemed to work.

In eight long innings, Carlton threw 157 pitches while striking out 10 and walking six.

After K.C. pitcher Larry Gura retired the first 13 hitters, the Phils staked Carlton to a 2-0 lead in the fifth on an infield single by DH Keith Moreland, a double by Garry Maddox, a Manny Trillo sacrifice fly and a Larry Bowa single.

The Royals got an unearned run in the sixth, set up by a Trillo throwing error. Then came the seventh, when Steve Carlton did his Venus de Milo imitation.

It was a mess. Lefty went in with a 2-1 lead, but three walks, a sacrifice bunt, a double and a sacrifice fly later, he staggered to the dugout trailing, 4-2.

And when Dan Quisenberry, the American League’s Fireman of the Year with 33 saves, came in to replace Gura, and set the Phils down 1-2-3 in the seventh on three ground balls, it looked bleak.

But in the bottom of the eighth, catcher Bob Boone worked a walk and scored on a Del Unser pinch-double to the left-center alley. It was Unser’s third consecutive hit in post-season play.

“He’s unreal,” Mike Schmidt said. Three batters later, Schmidt would massacre reality himself.

After Pete Rose moved Unser to third with a groundout to the right side, Bake McBride tied it at 4-4 with a single to right.

On Quisenberry’s next pitch, Schmidt socked a screaming 2-iron shot off the right field wall, driving in McBride. Moreland followed, singling in Schmidt, and Ron Reed pitched a strong ninth inning that saved the 6-4 win for Carlton.

After hitting 48 regular-season homers, Schmidt struggled through the playoffs against Houston, hitting .208 with only one RBI. So the big double was a vindication of sorts for Schmidt, who’s never been known as a team leader during post-season play.

“If you don’t to that (be a leader),” Schmidt said, “you don’t have a good playoff. It’s that simple… It’s ironic that I had the year that I had and now, when it means the most, I was completely humble. My teammates did it. I did nothing and they all did it. And that’s why this is a great ballclub.”

All the news wasn’t great, though. Greg Luzinski, who missed Game 2 with an intestinal virus, was questionable for the next one in K.C. Garry Maddox took a nasty self-inflicted foul ball off his left knee. And Dick Ruthven, the scheduled Game 3 starter, was fighting a wicked cold.

Nevertheless, Larry Bowa, intoxicated with a 2-0 Series lead, was enthusiastic.

“We’re right down to another best-of-three series on the road,” he said. “Montreal (the division-clinching series), best-of-three, and we did it. Houston, best-of-three, and we lose the first and look buried in the next two and we did it.

“Hey, ain’t nothing going to scare this team now.”

Game 3: LOB Equals SOS For Phils

By Rich Hoffmann

In the box score, in the middle of the box score, buried in the middle of the box score, is the left-on-base statistic.

LOB. Those three little letters have sent more baseball managers into premature careers as insurance salesmen than even Charles O. Finley.

In Game 3, the first at Kansas City’s Royals Stadium, the Phils tied all kinds of World Series records for runners left on base. They stranded 14 in regulation time, tying one record, and one more in the 10th inning to tie the record for men left on in extra innings.

All these LOBs just gave the Royals a bunch of chances to win their first Series game ever, which they finally did with a run in the 10th off Tug McGraw.

Dallas Green was still a manager and not a good-hands person after the 4-3 loss, but his team had blown a chance to deal the Royals what was historically been a World Series death blow, a 3-0 deficit.

“We had a chance to crush this team tonight and we didn’t do it,” Green said. “We had a chance to push Kansas City right over the edge. Dick Ruthven pitched a magnificent ballgame, but we didn’t get it done for him.”

Kansas City third baseman George Brett was a little more graphic.

“If we lose,” Brett said, “I think everybody’s going to feel like they’ve got hemorrhoids.”

Brett, whose proctologist was the first ever interviewed by a pack of sportswriters, underwent surgery on the off-day before Game 3 to rectify his celebrated problem. In the first inning, Brett testified to the surgery’s success, ripping a home run off Ruthven to give K.C. a 1-0 lead.

The Phils tied it in the second off Royals pitcher Rich Gale with two singles, a walk and an infield out.

The game continued to seesaw. A Willie Aikens triple followed by a Hal McRae single made it 2-1 Kansas City; a Mike Schmidt leadoff homer made it 2-2 after 4½.

An Amos Otis homer made it 3-2 K.C. after seven innings; Larry Bowa’s infield hit and stolen base and a Pete Rose RBI single made it 3-3 after 7½.

All the while, the Phillies had been stranding more people than live in many Missouri whistlestops. Two in the first, three in the second, two in the third, one in the fifth, two in the sixth, two in the eighth- a ton of stranded human flesh that came back to haunt the stranders.

In the top of the 10th inning, the Phils had their last shot and, like the rest of the night, it fell short.

A Bob Boone single and a Greg Gross sacrifice put the go-ahead run on second with one out. Reliever Dan Quisenberry (in the game since killing an eighth-inning rally) walked Pete Rose intentionally to get to Mike Schmidt, a large risk considering Schmidt was 4-for-10 off Royals pitching up to that point.

Swinging at Quisenberry’s first pitch, as he had done when he hit the game-winner in Game 2, Schmidt lined a low screamer toward the right side. Second baseman Frank White dove and grabbed the shot and easily doubled Boone off second.

In the bottom of the 10th, with Tug McGraw pitching in relief, U.L. Washington singled, Willies Wilson walked, Boone threw out Washington stealing and White struck out.

Two out, fast runner on first in Willie Wilson. Sure-to-be-running Willie Wilson.

A short-hop throw to second that Larry Bowa couldn’t handle allowed Wilson to steal second, and subsequently, George Brett was walked. Willie Aikens followed with a slicing liner to left-center, and the Phillies had lost their first game of the 1980 Series.

“I got the ball up to (Aikens),” McGraw said, “and he hit the hell out of it. We’ve been winning as a team and tonight we lost as a team. We had an opportunity to blow them out in four or five different innings and didn’t do it.”

Besides the usual post-loss gloom, there was fire in the Philadelphia clubhouse. Greg Luzinski aid he was fit as a fiddle and ready for left field, or at least the DH, after his virus. But he didn’t play, and burned afterward.

“Nobody asked me how I felt,” Luzinski said. “Nobody asked me if I could play. Nothing surprises me around here anymore. I guess the handwriting is on the wall.”

Even the Phillie Phanatic had it rough. Royals management refused to let him do his full routine, saying it would get in the way of the game. So he sat, too.

The loss was a tough one, and afterward, Dallas Green was asked about how it might have killed whatever momentum the Phillies had built up in the first two wins at home.

“All you writers make a big deal out of momentum,” Green snapped. “But I don’t think in a World Series that means a whole lot… We left 15 guys on. If we’d plated a few of them, it would have been a different story.”

As, would-haves. They’re the fuel for many a hot-stove league argument.

Unfortunately, they’re not good for much else.

Game 4: Aikens Is Big Hit as Royals Pull Even

By Rich Hoffmann

A look at the Game 4 line score indicated it was a pretty paltry offering by the Bowie Kuhn Repertory Company. The Royals got four runs in the first, one in the second, and held on for a 5-3, Series-evening victory.

Line scores don’t deal in the dramatic, though, and this one had a couple of first-rate sub-plots.

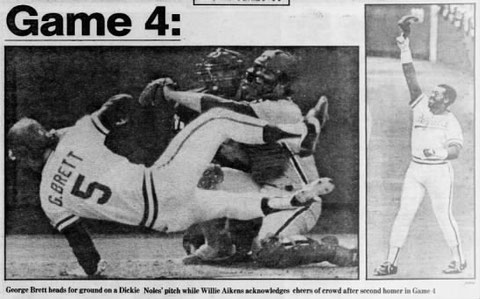

Most prominently, there was “L’Affaire Brushback,” a one-act melodrama starring George Brett, Dickie Noles and K.C. Manager Jim Frey.

Not to be overshadowed, though, was that old Series chestnut, “Attaining Superstar Status During a Few Days in October.” Previous stars of this exercise in high farce include Bucky Dent and Gene Tenace. This autumn’s leading man was one Willie Aikens, whose two homers in Game 4 gave him four for the Series, one short of the record help by that noted dungarees peddler, Reggie Jackson.

Aikens’ two blasts, in the first and second innings, made him only the fourth player to hit home runs in consecutive innings.

To set the scene for “L’Affaire Brushback,” the Royals knocked out Phils starter Larry Christenson with a four-run first inning, including Aikens’ first homer. The Phils came back with a run in the top of the second, Aikens’ second homer in the bottom of the second made it 5-1, and that’s where it stood when Brett reached center stage with two outs in the bottom of the fourth.

He swung and missed at Noles’ first pitch, on the outer half of the plate. He fouled off the second pitch, which was in a similar spot. The third pitch, intentionally or not, sent Brett into a dramatic spin to the dirt, missing his head by inches.

There is a bit of John Wayne in George Brett. He slowly picked himself up after his brush with death and laughed.

“I was laughing because it didn’t hit me,” he said. “I was striding right into it and I was lucky to get out of the way. It was a good hard fastball. I honestly don’t know how I got out of the way.”

But the big question remained: Was the pitch in the script? Was Dickie Noles throwing at George Brett?

“It he was, he was,” Brett said. “If he was trying to get me, he’s 0-for-1. If he wasn’t, it’s no big deal.”

No to Kansas City Manager Jim Frey, it wasn’t. He rushed in from stage right and, with the aid of numerous hand gestures, delivered his soliloquy, loudly projecting it to the furthest reaches of the mezzanine.

“Throw not at my superstar,” was its gist. “Hurt not the franchise.”

“I thought it was a knockdown pitch,” he later told the groundlings outside his dressing room. “Anytime a team gets off to a big early lead and hits some long balls and a good hitter comes up later and gets knocked down on an 0-2 pitch, I call that a knockdown pitch. I went out and all I said was that I wanted to stop it right away. Then Pete (Rose) said he wasn’t throwing at him.

“I said to him that he didn’t know if it was or wasn’t a knockdown pitch and I didn’t know that it was or wasn’t a knockdown pitch. Only the pitcher knows….”

And Noles, the pitcher, answered the critics thusly:

“You have to use both sides of the plate,” Noles said. “You can’t throw him a fastball low and away. I’ll be in Kansas City Memorial Hospital.

“The only reason he (Frey) came out is because it’s George Brett up there. If Frank White or someone else had been up there, he wouldn’t have done a damn thing. And the pitch wasn’t that far inside. But he’s the manager. He has to fight for his players. If I were the manager, I’d fight for my players.”

Despite less than rave reviews for his performance (the scribes decried his overacting), Frey’s theatrics were successful. Umpire Don Denkinger went to the mound and issued an official warning. And the rest of the game continued without such histrionics.

The denouement began after just 22 Larry Christenson pitches. Willie Wilson led off the top of the first with a single to left. An errant L.C. pickoff attempt moved Wilson to third. Two batters later, a George Brett triple scored Wilson, and Aikens’ first homer of the day, an epic shot into the right-field waterfall, made it 3-0.

“That’s a tough pitch (the inside fastball) to make for a righthander who stands of the far side of the rubber,” said Christenson, whose tragic demise soon followed. “It’s the first inning, I’m not sharp with it yet. It’s the first time I’ve been on that mound… I wasn’t gripping the ball real well.

“Hey, none of that is really an excuse. I just wasn’t able to make that pitch.”

“I’m a streak hitter,” said Aikens, the latest of the Kuhnian heroes, “and when I get in a streak, I’m capable of five or six homers in a week.”

“I’m in a pretty good streak now.”

Hal McRae followed with a double that would have been a single if Garry Maddox hustled the ball in a little quicker. An RBI double off the bat of Amos Otis and Christenson was banished to the showers.

The rest of the game was an anticlimax. The Phils scratched out single runs in the seventh and eighth, but fell short.

Dallas Green, the veteran character actor who now manages the unpredictable Philadelphia troupe, panned his company’s performance.

“It looked to me,” Green said, “like we weren’t totally ready to play today…. You can’t keep hoping for rallies. You can’t always call on character. Eventually, base hits and pitching are going to have to do the job.”

Del Unser, who specializes in cameo performances, expressed no worry.

“This, to me, is like a little road trip, and they’ve won the first two,” he said. “Now we’ve got to start playing together, executing, doing the things we have to do to win games.

“But pressure? We’re in the World Series, man. There ain’t no pressure here. Getting here was where the pressure was.”

And on that evening, with the curtain falling on what was all of a sudden a tied-up Series, Del Unser’s words rung just a bit hollow.

Game 5: Schmidt’s Hit Melts Frey’s Strategy in 9th

By Rich Hoffmann

Everyone involved in this tourney knew that after the Royals tied it at 2-2, Game 5 would be the axis on which the series would pivot. A loss eliminated neither team, but still, the prospect of the loser having to win two straight with the loot on the line was hardly appealing.

It was a game, even more than the previous four, in which the smallest mistake would be held up to ridicule by the gods of the typewriter assembled above. The tiniest error in judgment, the most minute miscue, would be exposed by the scions of American sports journalism and picked apart like a vulture would ravage a carcass rotting in the sun.

The heat, as they say, was on. And K.C. manager Jim Frey melted, and his Royals dropped the pivotal fifth game at home, 4-3.

Frey’s mistake was in paying attention to the short run and ignoring the obvious. In the ninth inning, with the Royals leading 3-2, with no one out and no one on, Frey had his third baseman, George Brett, playing in for the bunt with Mike Schmidt at the plate.

Now, Mike Schmidt is not a good-field, no-hit shortstop. He’s not the eighth-place hitter. Mike Schmidt is the 1980 major league home run champion. During the regular season, the guy hit 48 home runs. And in the fourth inning that very afternoon, he slugged a mammoth homer to straightaway center that gave the Phils a short-lived 2-0 lead.

In short, Mike Schmidt has never been mistaken for either Punch or Judy, but in the dusk of the ninth inning of Game 5, Jim Frey had his third baseman playing him that way. Frey was fixated on two earlier Series incidents in which Schmidt tried bunts in crucial situations. He was playing a hunch, and it backfired.

With Brett in, Schmidt lined a shot to his left. With the third baseman at normal depth, it’s a routine out, but playing tight, Brett had to dive and barely got a glove on it, deflecting it toward shortstop. Schmidt was on first and the winning rally was started.

“No way I was gonna bunt in that situation,” Schmidt said. “Not one run down in the ninth. My job there is to get a good pitch, try and drive it, try to hit a double, maybe even hit the ball out of the park. No way would I think of trying to get on base with a bunt. But now that you mention it, my bunting twice here might have put that thought in their minds. I didn’t really notice how close George was playing me. I was just aware of him guarding the line. If he’s back on that ball, I guess he makes a fairly routine play.”

George Brett wasn’t guessing. “If I’m playing normally,” he said, “I make that play.”

But he wasn’t, and he didn’t, and Schmidt was on first. Del Unser, pinch-hitting for Lonnie Smith, ripped a double past first baseman Willie Aikens, he of the brass glove and clay feet, scoring Schmidt and tying the game, 3-3. Frey had slick-fielding Pete LaCock on the bench, but he decided against making the late-inning defensive switch he’d made all season. Aikens, on fire at the plate, was due up in the ninth, so Frey gambled on his defense and lost.

DH Keith Moreland’s bunt moved Unser to third, and Garry Maddox’ bouncer to third left Unser there with two outs.

Manny Trillo was the batter. He ripped a slider back to the box, the ball deflecting off reliever Dan Quisenberry’s forearm and ricocheting toward third base. Trillo beat it out, Unser scored, and the Phils were ahead, 4-3.

The sight of Unser, a class guy, crossing the plate with the go-ahead run warmed many Philadelphia hearts. Unser’s success as a pinch-hitter in the playoffs and World Series, though not unprecedented, was one of the highlights of the post-season.

“As a pinch-hitter, you’ve gotta come of that bench swinging,” he said. “There are gonna be times when you go up there and it looks like that pitcher is throwing BBs. There will be other times when it looks like he’s throwing beachballs. Either way, you’ve gotta swing the bat. You’ve gotta make something happen.”

Tug McGraw, who’d been in the game in relief of rookie starter Marty Bystrom since the seventh inning, had to survive a heart-thumping ninth to nail it down, striking out Jose Cardenal with the bases loaded.

“Jose’s no piece of cake right now,” Tug said. But Jose’s swing said otherwise.

“I look at the bright side,” said Cardenal, a man gifted with the ability to see things others can’t. “A hit tied the game. It was a strike, I had to swing.”

“I’m still a lucky guy. The Mets drop me, I come to a team like this and I’m in the World Series. How lucky can you get?”

The man obviously hadn’t had much experience with luck. Dan Quisenberry, the witty reliever who’d had more than his share of rocky outings this Series, knew the real result of his team’s mistake-filled, fifth-game loss. If the Royals were to win the whole shebang, they’d have to take the final two games in Philadelphia.

“Now,” Quisenberry said, “we’re up against the Berlin Wall. The East side of it.”

Game 6: McGraw Strikes Out the Mighty K.C.

By Rich Hoffmann

Mike Schmidt had the most fervent of wishes for Game 6. More than a wish, it was a plea.

“I’m just looking forward to that 1-2-3 ninth inning one of these days,” he said. “Maybe Lefty will give it to us.”

Well, Lefty came close, throwing a four-hitter for seven innings. But he started losing it in the eighth, with a 4-0 lead, and Dallas Green looked to the bullpen.

Which meant that Tug McGraw, his over-worked arm hanging my the most frayed of muscles and tendons, would have to reach back one more time to try to nail down the Phillies’ first World Series title in their 97-year history.

Which also meant that there would be no 1-2-3 ninth.

“With all those people watching on television, I hate to make the game boring,” Tug McGraw said, only semi-kiddingly.

McGraw, the man who has brought on more late-inning indigestion than any Vet hot dog ever did, manufactured another of his patented gas-pain finishes, working out of bases-loaded jams in both the eighth and ninth.

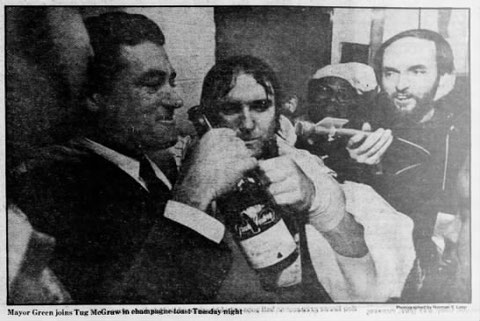

And when it was over, the Phillies were champions.

“The eighth inning was fun,” McGraw remembered after the 4-1 win, “but my arm was so tired in the ninth all I wanted was for the Royals to please hit the ball at one of our guys. I could see the security people lining up, all the animals behind home plate. Tired as I felt, I wasn’t about to go to the dogs.”

Dallas Green wasn’t so sure. A walk to Willie Aikens and singles by John Wathan and ex-Phil Jose Cardenal had something to do with his uncertainty.

“I was talking to Garry Maddox,” Green said, “and he said, ‘I think he’s going for the save,’ and I said, ‘Christ, I think you’re right. Maybe I better go talk to him.’ So I went and talked to him and said, ‘Hey, Tug, let’s not make this SOB as overly exciting as we’re trying here.’”

All kinds of memories flash at such times: Garry Maddox’ big 15th inning hit to win a game in the final week against the Cubs; Bob Boone’s two-out, ninth-inning hit to keep the Division-clincher against Montreal alive; the incredible eighth-inning rally against Nolan Ryan that helped secure the pennant. For the better part of the month, it had seemed the Phils were somehow predestined to win this thing.

With all the comebacks, after 97 years of comedowns, it looked like the big right fielder in the sky had decided this was finally to be the Phillies’ year.

But those earlier events had only been hints; with one out in the ninth came the definitive sign.

It started as a simple foul popup in front of the Philadelphia dugout. Catcher Bob Boone ambled under it; Pete Rose came over from first base to watch. The ball came down into Boone’s glove, like a thousand times before.

But then it popped out, and the 65,838 assembled lunatics gasped audibly. For a millisecond, the folks on Mt. Olympus seemed to have forgotten their favorites. But almost immediately, they sent Pete Rose as their messenger to rescue the situation. He whipped out his glove and snared the bumble. The Sign had been received; two men were out.

Willie Wilson was Tug McGraw’s last hurdle. After a 230-hit regular season, the speedster had already tied a Series record for most strikeouts. Reaching a 1-2 count, McGraw reached back and fired. He already had invented the Bo Dered (“it has a nice little tail on it”), the Peggy Lee (“is that all there is?”), and John Jameson (“straight- like I drink it”) fastballs in this crazy season.

He didn’t give a name to the 1-2 fastball he threw to Willie Wilson, but if he had, it would have been the Mao Tse-Tung- it was like a slow boat to China. Somehow it reached the plate. Wilson swung through it, and the Phils had won the Series.

“I don’t know what Dallas had in mind,” McGraw said, “but if I didn’t get Wilson I was calling him to the mound because I had nothing left. Nothing.”

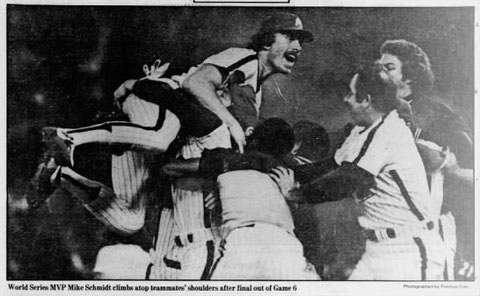

Mike Schmidt, the Series MVP, gave the Phils all the runs they needed with a two-run single in the third inning. Lonnie Smith scored a run in the fifth on an infield out, and Boone singled home Larry Bowa in the sixth to account for the other Phillies run.

And when Carlton, the winning pitcher, ran dry in the eighth, it was in the hands of Tug McGraw. Very able (but dramatic) hands, as it turned out.

“I think this is the proudest I’ll ever be as a baseball player,” Tug said. “It took us a few months under Dallas Green to catch on to what he was saying, but then we got he program together. To me, Dallas is one helluva man.”

Then, Tug McGraw put the whole wild scene into perspective.

“Now, if you’ll excuse me,” he said, “I need to get back to the clubhouse, where there’s more champagne.”

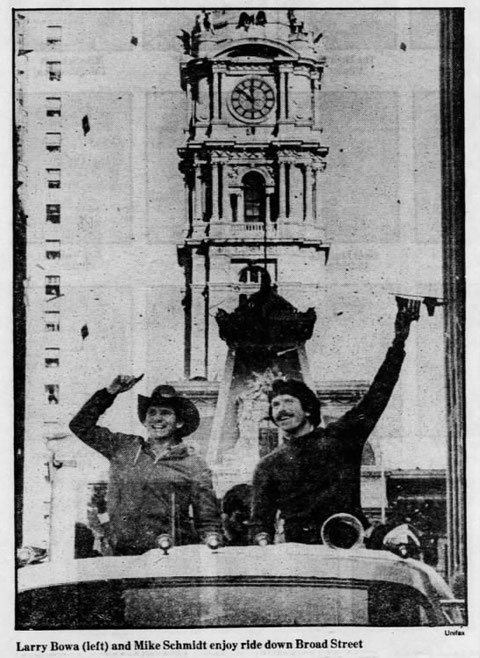

I Loved The Parade

By Phillie Phanatic

People always talk in symbols when they talk about winning the World Series. It’s not so much winning the best of 7; the talk is of the symbols, of fighting for two things- the championship ring and the Broad Street parade.

The players’ rings are on order, but the parade was yesterday, and it’s something that no one involved will ever forget. It also taught the Phanatic a lesson:

If anyone out there is interested in becoming a dictator, the easiest way to pull it off is to put on a green feathered suit and get involved with a world champion baseball team in a town that hasn’t had one in 97 years.

Everyone was just in a great mood, and they were so excited, they cheered anything. Any move the Phanatic made along the way, the response was unbelievable.

The Phanatic was in the last of a series of flatbed trucks, all by himself, at the very end of the parade. And every time he moved a muscle, the crowd would react. Loudly.

Walk to the left side of the flatbed… roar.

Walk to the right side… roar.

Raise one finger…We’re No. 1.

The players and everyone else in the parade deserve medals. Not for winning, but for getting up in time to be there. It was really funny to watch the players all show up at the staging area and look so bad. They all had sunglasses on.

One guy whom the Phanatic didn’t expect to see was Steve Carlton. It would just be a logical offshoot of his private nature not to be at the parade, but there he was. The night before, the Phanatic remembers asking him if he was going to be there, and he answered, “I don’t know.” But bright and early, he was on a float headed down Broad Street.

One nice thing the Phillies did was let everyone in the organization- the whole front-office gang- ride in the parade. It was the whole Phillies family together for a big reunion, swapping stories about the night before. There must have been about 250 people riding in the parade, and they probably had a combined total of about 10 hours of sleep.

The Phanatic remembers as the parade started, there were a lot of people on the sidewalks and some of the wives said, “Wow, look at all the people.”

Then we turned the corner onto Broad Street, and there were people everywhere. Sitting on the stoplights. Sitting on the clothespin at City Hall. Hanging out the windows. Everywhere.

Some of ‘em were pretty wild, too. One guy was totally painted red. Another woman’s hair was dyed red. And then there was this one guy and his son whom I’ll never forget.

Down a way on the parade route, the guy was all dressed up in a clown suit with red and white pinstripes, screaming his head off. And the kid was terror-stricken, sitting on his shoulders.

Now a lot of kids were holding their ears, crying, really frightened because it was so noisy. But this kid was really scared. The Phanatic couldn’t hear him, it was that loud, but he could read his lips, yelling “Daaaaadddy, Daaaaddddy, Daaaaddddy.” And Daddy just kept jumping up and down and screaming.

So the Phanatic leaned over and touched the little kid on the head, and he screamed some more.

It was like that the whole way, shaking hands, kissing babies, the whole thing. It was like the Phanatic was running for President.

When we finally got to JFK Stadium, the crowd there was wild, too. The Phanatic got a big cheer, got off the flatbed and did a little dance, and then headed home. It was nice to be a part of it, but this was the players’ show.

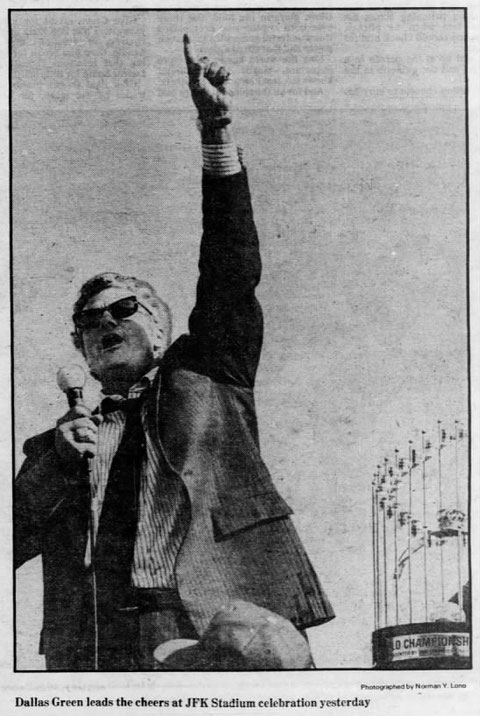

Heading out of the stadium, the last voice the Phanatic heard was Dallas Green’s. “You people are beautiful,” he boomed. “This baseball team is beautiful. Everyone is beautiful.”

Everyone there screamed their agreement. And just then, the Phanatic realized that not only the guy in the green suit, but the manager, too, could be a dictator for a day.

For the Phanatic, it’s been an incredible year. Nothing could ever top this. Nothing will ever be like it.

Tomorrow? The Phanatic will be at a Little League banquet in Wilmington.