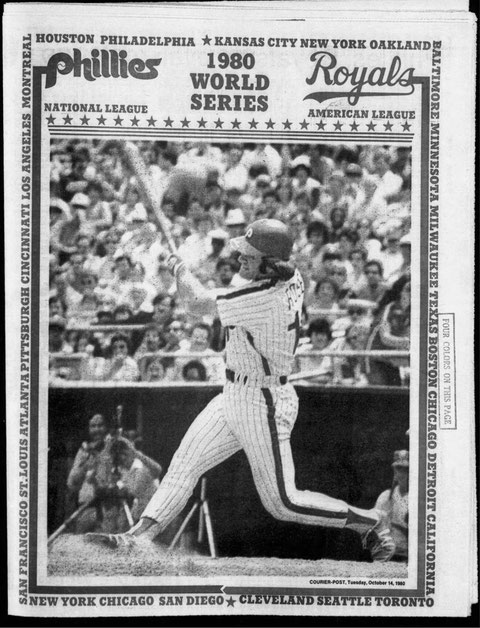

Camden Courier-Post World Series Special - October 14, 1980

Phillies, Royals an even matchup

By Bob Kenney, Courier-Post Sports Editor

PHILADELPHIA – Although the World Series may be an anti-climax to both the Royals and the Phillies, the two teams are so evenly matched anything can happen.

Kansas City coasted to the Western Division title, then took out four years of frustration on the New York Yankees to win the American League pennant.

"We were hungrier this year," said Paul Splittorff, the veteran Royal pitcher. "Maybe beating the Yankees was an obsession."

Philadelphia roared from far back to overtake Montreal and win the Eastern Division, then eliminated Houston in what is being called the greatest playoff series ever, to become the National League champions.

"The pressure is off now. We're finally in the World Series," said Mike Schmidt, the Phillies' slugging third baseman.

Although both clubs threw everything into winning the pennant, don't look for either team to ease up in the best-of-seven showdown which gets underway tonight in Veterans Stadium here.

Kansas City will go in better rested. Philadelphia will go in with the momentum.

After that, there are some amazing similarities between the two teams. Both won divisional crowns in 1976-77-78, but failed to win their pennants. Both failed to make the playoffs last year, but rebounded superbly this year.

Both are managed by rookies. Former Baltimore coach Jim Frey is the Kansas City manager. Former farm director Dallas Green is the Philadelphia boss.

Both rely on speed and solid defense since both play on artificial turf; both rely on leadership from super third basemen, and both teams have solid pitching anchored by one outstanding reliever.

George Brett almost his .400 leading Kansas City to the crown. Schmidt banged out 48 home runs while setting the pace for Philadelphia.

"I know people will be comparing George and me, but there are 18 great players showing themselves to the world," said Schmidt. "But it will be some buildup."\

Phillies' fans feel there is no better bullpen ace than lefty Tug McGraw, who allowed just one run the last 35 days of the season. Royal boosters point to the 14 wins and 33 saves contributed by submarine reliever Dan Quisenberry.

Kansas City hit 115 home runs as a team. Philadelphia hit 117.

Kansas City committed 140 errors. Philadelphia made 137.

Kansas City hit five more triples than Philadelphia.

Kansas City hit six less doubles than Philadelphia.

As a team, the Royals batted .286 to hold the edge.

But Philadelphia's earned run average is almost a half-run per game better.

"We're a good offensive team," said Frey. "We do a lot of running and stealing. There will be no tricks, no magic, no surprises. We're an underrated team."

He could have been speaking for Green, who managed what he called "grind it out baseball" built around the hit and run play.

Even the position-by-position matchup leaves little to choose.

Kansas City uses Willie Mays Aikens at first base and the big lefty has knocked in 98 runs with 20 homers. Pete LaCock is the defensive replacement and the team's top pinch-hitter.

Rose gives the Phillies the edge defensively and contributed 185 hits but can't match the Kansas City power. Give the Phillies the advantage on the intangibles.

Both teams have outstanding second basemen, probably the best in each league. Frank White is fast, has good range and throws well. He made only 10 errors and enjoyed his finest season at the plate, hitting .264.

Manny Trillo is not as fast, has shorter range but throws better. He made 11 errors and enjoyed his finest year at bat, hitting .292. Call it even.

U. L. Washington has developed into one of the best young shortstops in the game. He's a Garry Templeton type who will make the great play then boot an easy roller. He made 32 errors this year but has great range and speed. He hit .273 and drove in 53 runs.

Larry Bowa is in the twilight of his career for Philadelphia. He committed a high number of errors by his standards, 17, and has slowed a step in the field. But he has played like a man possessed the past month and raised his average to .267, its high mark of the year. Call them even.

George Brett is the best player in the game today. He has developed into a fine defensive third baseman and made only 17 errors. He gets to as many balls as Schmidt but has a weaker arm. He hit .390 and led the Royals in home runs with 24 and runs batted in with 118.

Schmidt is a brilliant player, second to none but Brett. He hit .286 and knocked in 121 runs. He makes the tough plays look easy but committed 27 errors. Give a slight edge to Brett.

Willie Wilson is baseball's fastest player. He handles left field very well for the Royals and as a switch-hitting leadoff man banged out a league leading 230 hits and scored 133 runs.

Amos Otis didn't hit as well as usual but is over some injury problems and gives the club a solid center fielder. Clint Hurdle, .294 with 10 homers, and John Wathan, .305 with 58 runs batted in, divide duties in right field.

Philadelphia's outfield revolved around defensive whiz Garry Maddox, the best in baseball as a center fielder tracking down alley shots. Bake McBride hit a career high .309 in right field and Greg Luzinski, 19 home runs, and Lonnie Smith, .333, split assignments in left the second half of the season. Rate the outfield even.

Darrell Porter didn't hit as well as usual, only .249, but is one of the best catchers in the game. Bob Boone also struggled, hitting only .229 but driving in 55 runs, for the Phillies. Still even.

Kansas City gets an edge with the designated hitter. Hal McRae is one of the best. He hit .297 and drove in 83 runs. The Phillies didn't use a DH during the season and will probably play Luzinski against lefties and Del Unser against righthanders.

The Royals have Dennis Leonard, a power throwing righthander, and Larry Gura, a slow ball lefty, leading the pitching staff. Leonard won 20 games, Gura 18 with four shutouts.

The Phillies counter with Steve Carlton, who won 24 games as the league's best lefty, and Dick Ruthven, a 17-game winner.

Lefty Splittorff won 14, Rich Gale 13 and Renie Martin 10 for the Royals. Bob Walk won 11 and the rest of the Phillies victories were scattered. Give the Kansas City team a slight edge in starting pitching. The Phillies, though, seem to have the better bench. Keith Moreland hit .314 and is a solid pinch-hitter. Greg Gross, a lefty, is a lifetime .300 hitter who gives the team contact when needed.

Kansas City has Jamie Quirk and Jose Cardenal off the bench, but the Phillies have the better bats in a pinch.

This one should take seven to decide unless the Phillies are too drained mentally and physically from the Houston shootout.

Dallas Green

He stepped on toes, spanked egos, lectured audiences that hated what he had to say, pleaded with people he simple wanted to punch, and, most of all, believed for those who couldn't believe in themselves.

By Ray W. Kelly of the Courier-Post

PHILADELPHIA – Years from now, when the Phillies' hair raising march to the 1980 pennant is relegated to the history books and the World Series becomes little more than a few wondrous moments in the minds of baseball fans, Dallas Green's name won't be much more than a footnote.

Yet, the man who risked the security of a promising career in the front office to tackle the frightening job of managing one of the most temperamental teams in creation, deserves to be canonized, cast in bronze and given a free pass to the universe.

He did what no one else could do. He got the Phillies to finally play to their potential and not just statistically. They could always do that with one arm tied behind their backs.

This time, Green taught them that success isn't just found in the batting stroke and in a well-thrown slider, but also in the heart and soul.

What the former pitcher for the Phillies did was to ask himself one question whenever confronted by a decision. Is it going to help us win, today?

Seems simple, doesn't it? Well, it wasn't.

No one else could do it. Not Frank Lucchesi, who loved his players too much. Not Danny Ozark, who gambled his future on the hope that peace and happiness in the clubhouse would bring the ultimate victory. And certainly not owner Ruly Carpenter, who could never pit himself against his own family.

Like a man who wouldn't hurt a fly in his civilian life but suddenly found himself storming a beachhead with blazing machine guns under each arm, Green somehow found his strength to go against his baseball and corporate inklings. All in the name of victory.

He stepped on toes, spanked egos, lectured audiences that hated what he had to say, pleaded with people he simply wanted to punch, and, most of all, believed for those who couldn't believe in themselves.

"If I'm going to do this job, I'm going to do it my way," he said at the outset. And, he did.

Green walked a high wire over an ocean of sharks as the winds of discontent buffeted him from all sides. And, Philly is a town where everyone, legendary stars and heavyweight media, can blow at gale force.

But, he hit them all between the eyes with what he believed to be the truth. He benched all-stars, knowing they had the talent to come back and make him look the fool, a possibility that delighted him.

He threw writers out of his clubhouse, knowing they had the power to bury his public image. He could have care less. "Bear down," he told more than one scribe.

He was both friend, and foe, public relations man and critic, savior and villain to just about everyone. You got what you deserved.

It would have been easy to hate Green completely, except for one thing, his motivation. Winning was his bottom line, not a desire to be liked.

Philadelphia was an organization that seemed dedicated to the idea of winning a pennant without anyone ever getting his feelings hurt- until Green came along.

Injured feelings were the least of his concerns. And, that included his own. He turned the other cheek more times than a nightclub stripper, shrugging off the public criticism of his players by saying, "They have a right to their opinion."

But Green had an opinion of his own, which he didn't keep to himself, much to the chagrin of the players and the owner.

Where Ozark spent most of his waking hours sweeping responsibility under the rug, Green stood up and pointed a finger. This was one season where everyone was going to accept both the responsibility and consequences of their contributions.

There is not another man in all of baseball who could have pulled it off. Green alone had the knowledge of the organization, the respect of the younger players and the unique clout needed to take on a team that would have butchered any other newcomer. The players believed the team was the most exclusive country club in the nation.

You see, Green was not only secure because of this already predetermined future as the heir-apparent to General Manager Paul Owens, he also was a man Carpenter respected and trusted as a friend.

Green had all the aces. His credentials as a handler of pitchers were unquestioned. His generalship in the handling of games was hard to belittle because he kept the counsel of the coaching staff that the players had already acknowledged as being competent.

And- here's the kicker- any player hoping to tug on Carpenter's heartstrings in order to take a detour around the manager soon discovered that Ruly was also growing tired of maintaining a happy family at all costs. Like Green, he too was weary of not winning.

It is to Carpenter's and Owens' credit that they had the foresight to see the opportunity that Green represented. And, they showed guts in backing him during the most difficult of times.

Think for a moment what it must have been like for Dallas to bench a guy like Greg Luzinski, whom he has known and admired for years. Then Green had to turn around at a later date and replace one of his farm system stars, Lonnie Smith, with Luzinski because he believed that, when it came to the playoffs, Bull was the guy who would help them win.

Multiply that constant flow of emotions a hundred times and you begin to get an idea of what the manager went through to bring the club home a winner.

He did it because he knew that winning was the cure for what has ailed the Phillies for years.

And in the end, he turned the most turbulent, distressing and unhappy season these players have ever seen into the most rewarding experience of their lives.

He showed them that they were better players and better people than they ever realized.

He made them winners.

Green's philosophy helps Vermeil wish best for Phils

By Vic Carucci of the Courier-Post

PHILADELPHIA – Dick Vermeil knows the Phillies are in the World Series, which, when you consider the extent of his baseball knowledge, is saying something.

The Eagles' head coach simply has no time for baseball or hockey or basketball or anything else that doesn't involve his football team.

To him, a sacrifice is when a special teams player stops somebody with his head. Bunting rings a bell, only because it happens to be the last name of one of his linebackers.

Vermeil does, however, know at least one thing about the Phillies: their manager, Dallas Green, shares his philosophy of ruling with an iron fist. For Vermeil, that's more than enough reason to root for the other professional sports franchise in town.

"I'm excited about seeing Dallas Green succeed, because I believe in his approach," Vermeil said. "I think, if he decides to stay with the team in that position, they'll be within this situation more often. With that kind of leadership and the kind of talent they're supposed to have, I believe they can win."

Vermeil hasn't seen a Phillies game this year, and he isn't planning to watch the World Series games in Veterans Stadium tonight or tomorrow.

"It will, in no way, distract me and my players in getting prepared to play Dallas. All it does is add real enthusiasm to this city," he said. "Can you imagine, if we can find a way to beat Dallas on Sunday and our Phillies can win two at home, how it would be here Sunday night? No cities react to the success of their major sports like Philadelphia does. I think our fans deserve it and Dallas Green and (Phils' owner) Ruly Carpenter deserve it."

The Eagles and Phillies enjoy a harmonious co-existence, which, according to Vermeil, is rare. The only thing that bothers the Eagles' coach about sharing the Vet with the Phillies is occasional parking problems when their practices conflict.

"I just hope they don't tow our cars away," Vermeil said. "That's what bleeps me off. Hell, you work in the stadium and have a parking place and they come and tow your car away. It upsets your players and coaches. That's the only thing I ask, is they leave our cars alone."

Vermeil also hopes Green's players appreciate what their manager has given them.

"No matter how gifted an athlete is, you still need discipline to bring people together to form the kind of character it took to win with their backs to the wall," Vermeil said. "It takes intensity and enthusiasm and you can't second-guess the guy who's in charge of making decisions.

"Sometimes, professional athletes forget what they're paid to do. They think they're also paid to manage, and they aren't. They're paid to play/"

In Vermeil's view, the Phillies' player who best exemplifies that attitude is Pete Rose.

"I like the Pete Rose-type personality," he said. "He could be playing linebacker for us right now."

Kansas City: All Business

Strong and quiet determination led team to largest winning margin of four champs

By Bruce Carnahan of the Kansas City Royals

It was really rather businesslike for Kansas City in 1980 when the Royals won their fourth American League Western Division title in the past five seasons. There were no loud noises from Kansas City, but to a player a strong and quiet determination to recapture the division title could be detected. The strong determination of the Royals resulted in the largest winning margin of the four 1980 major league division champions and Kansas City's fourth division crown in five years.

There was the magic of George Brett's bat with his 30-game hitting streak and quest for a .400 season and the batting title; the speed, hitting and brilliant play of emerging star Willie Wilson; the sparkling infield play of Gold Glove second baseman Frank White; the slugging of designated hitter Hal McRae and first baseman Willie Aikens; the anticipation of 20-win seasons by Larry Gura and Dennis Leonard; and 11-game winning streak by Rich Gale, and the clutch relief pitching of the unheralded Dan Quisenberry en route to the top bullpen performance in Kansas City baseball history.

Jim Frey was new to managing and new to Kansas City, but the 49-year-old skipper was not new to winning when he was named Royals' manager last October. He stepped out of the first base coaching box from the 1979 World Series for the Baltimore Orioles into the manager's post in Kansas City.

What Frey didn't anticipate for the season was a contagious injury situation in the early-going to five key players. Despite the rash of injuries, the Royals battled to make another of his spring training prophecies ("it's going to take 25 players to win this thing") prove true.

Through the Royals' first 80 games (July 6), Frey was able to field his "starting lineup" as a unit together in only two games. Regulars out for extended periods included Brett (bruised right heel and torn ligament in right ankle), Amos Otis (ruptured tendon in little finger), McRae (torn left calf muscle), Darrell Porter (attending a rehabilitation center) and Paul Splittorff (acute back spasms). During the stretch Brett and McRae each missed 35 games. Otis' first start came in game number 40 and Porter returned for game 19, but did not resume regular catching duties until mid-June. Splittorff was out of the rotation from May 8- June 2.

A month into the season the Royals were only at the .500 level, with a 12-12 record, following action on May 8, when the club was in fourth place two-and-a-half games off the pace. Kansas City then took off and posted a 24-9 record over the next 33 games to June 13 to climb into the top sport in the A. L. West with a six-game lead. The Royals actually moved into first, a spot the team would not relinquish the rest of the season, on May 23 with a 13-9 win at California.

From July 10 to August 20 the Royals became baseball's hottest team with a 31-9 record, winning an amazing 77 percent of their games during the span. As August turned into September, Kansas City turned off the lights on the rest of the division by climbing to a then season high 85-46 (.648) record and 20-game lead with approximately six weeks to play.

The Royals were so dominant during that stretch that the club went 17 consecutive series without losing a matchup, including one stretch of 13 consecutive winning sets (July 10- August 20).

Through the 40-game span the club hit .320 as a team with 34 home runs while averaging 11.6 hits and 6.20 runs per contest. The spurt boosted the team batting average to .290 by August 20.

Frey's prediction that the Royals offense would be productive was also true as the club led the league in hitting and ranked near the top in most categories. Like the Royals' previous division winning teams, the 1980 edition combined a potent hitting attack with speed on the bases, consistent pitching and solid defense to win the title.

The heart of the Royals day-to-day lineup included outstanding performances by Wilson, McRae, Otis, Brett, Aikens, Porter, White, U. L. Washington, John Wathan and Clint Hurdle. Most of the regulars enjoyed their top seasons at the plate or put together key stretches that played an important role in helping the club.

The bench was also of vital importance, especially during the early stages of the season when injuries hit the club hard and sidelined a number of players.

Dave Chalk, Rance Mulliniks, Jamie Quirk and Pete LaCock were called on to play a variety of positions and deliver important pinch hits. Rookie Onix Concepcion displayed his wares on the big league level for the first time after joining the parent club following a sparkling showing in the farm chain. Veteran Jose Cardenal joined the club late in the season and provided important righthanded hitting punch during the stretch drive.

Veterans Gura, Leonard and Splittorff returned to form and provided the consistency for the starting staff. Gale bounced back from an off-season in 1979 and after a slow start provided key wins and Renie Martin rallied to the task while working both in relief and as a starter. The rookie righthander won six of his first seven starts over one stretch while filling in for Splittorff when he was injured and out of the rotation.

Quisenberry provided the pitching staff with perhaps its biggest boost as he came out of the pen night after night to save crucial games. The submarining righthander figured in nearly half the club's wins while battling Yankee's bullpen ace Goose Gossage for Fireman-of-the-Year honors in the American League. Marty Pattin was again the dependable veteran and added depth to the relief corps along with rookie Jeff Twitty and southpaw Ken Brett.

Tough choice deciding which team was best

By Doug Frambes of the Courier-Post

Fans in New York, St. Louis, Brooklyn and Los Angeles, as well as in a few other major league cities, spend the Hot Stove League season happily comparing the strengths of the various teams which have represented their franchises in World Series play.

In Philadelphia, the discussions were always on a much more limited scale. The only teams to fly pennants were those of 1915 and 1950.

Now, at long last, a third flag has been won. But, only those approaching the four-score post in the game of life would have been able to see all three National League champions in action.

Comparisons between different generations is never conclusive, but always fascinating, and no game lends itself to them like baseball. Conditions change, but it still is three strikes and three outs, and the 90 feet between bases is the same as a century ago.

So, with the help of a multitude of record books, plus the recollections of a host of old-timers, it is time to enter the wonderful world of make-believe and try to visualize how the victors of today stand against the heroes of days gone by.

Some similarities arise immediately. All three champions possessed a pitcher who was a dominating force in his era. A top power-hitter was another constant, as were fancy-fielding shortstops and fleet center fielders.

Somebody way back when, maybe John McGraw or Connie Mack, or possibly old General Doubleday himself, concluded that the key to any great team was pitching. The axiom never has changed, so let us start on the mound.

For the first Philadelphia winner the pitching star was Grover Cleveland Alexander. Considered by many the greatest pitcher of them all, Alexander won 31 games and turned in an ERA of 1.22 in 1915, both tops in the league of course, and also led the circuit in innings pitched, strikeouts, shutouts and winning percentage.

The Whiz Kids of 1950 could counter with Robin Roberts. Robbie, then 24, won 20 games, the final a pulsating conquest of the potent Brooklyn Dodgers to nail down the pennant. He went on to six successive 20-game seasons and joined Alexander in the Hall of Fame.

Steve Carlton seems a sure bet to have his own bust at Cooperstown. The tall lefty entered the 20-victory lodge for the fifth time and statistically had a year topped only by his unforgettable 1972.

Behind Alexander, the only big winner was Erskine Mayer. The Phils' had another Hall-of-Famer to be in Eppa Rixey, but the big southpaw won only 11 games in an off year.

In 1950, Roberts had a great partner in Curt Simmons, but when the World Series came around he was called to service in the Korean conflict. Veterans Ken Heintzleman and Russ Meyer joined rookies Bubba Church and Bob Miller to give the team adequate starting pitching.

Carlton labored alone in the early weeks of 1980, but eventually Dick Ruthven and Larry Christenson recovered from arm woes, while Bob Walk and Marty Bystrom came up from Oklahoma City to stabilize matters down the stretch.

It appears pretty much a standoff, but who can argue with 31 victories and 36 complete games? A hesitant vote is cast for 1915 and Alexander the Great.

Relief pitching is, of course, another matter. In the old days, a starter was expected to go the route. In 1915, Alexander himself led the team in saves with three. Times had changed so much by 1950 that a relief specialist named Jim Konstanty was the Most Valuable Player in the National League. Tug McGraw blazed through September so sensationally this year that he rekindled memories of Konstanty.

The relief category would need a non-applicable column for the old-timers, and this voter will call a dead heat between the two later bullpens.

All three teams had receivers who were highly respected in the profession. Bill Killefer was Alexander's favorite catcher, and when Alex was traded in a most unpopular deal in 1918, his battery mate went along. A weak hitter with little power, Killefer was best known for his grasp of the game. He went on to manage in the majors for nine years.

Andy Seminick was the best distance hitter. Older than most of the Whiz Kids, Andy, through hard work, became a better than adequate defensive man and always was a rock behind the plate. Bob Boone, although below his best while fighting back from an injury, has been a Gold-Glove recipient and for three consecutive years hit in the .280. Boonie has the edge here.

There is no contest at first base. Pete Rose totally outclasses his competition offensively, and in no time became excellent in the field. Fred Luderus of the original champs was a steady slugger in his day and handled the mitt well enough, but his name never will be mentioned with that of Rose.

Ed Waitkus of the 1950 gang was adroit defensively and a competent line drive hitter. His was the most unusual baseball story of the day. When the Phillies were in Chicago during the 1949 season, he received a telephone call from a girl he did not know. When he appeared at her hotel room door, she shot and nearly killed him. To the surprise of many he came to spring training the next year, regained his job and went on to have a creditable year.

Manny Trillo wins decisively at second base. A Gold Glover in the field, he also outclassed the others at the plate. Mike Goliat had only one year as a regular and it was 1950. He was an average player at best, but did have the knack of hitting Brooklyn's great pitcher, Don Newcomb, with authority. Bert Niehoff was rated by his contemporaries of the pre-World War I days as a capable infielder who could steal a base, but was not much help with the bat.

Shortstop is the toughest to rate. Davey Bancroft of the 1915 squad showed enough that when his playing days were over he became one of the few men from that position to gain admittance to Cooperstown. Granny Hamner of the Whiz Kids was noted for his hitting, particularly in the clutch. Larry Bowa fell off slightly defensively this year, but for a decade played shortstop as well as it could be played.

Bancroft was a rookie in 1915, but immediately solidified the infield and played a major role in the team's jump from sixth place to first. Like Bowa, he was a switch hitter, who achieved a career average of .279. Admired as a fielder by John McGraw, who later brought him to the New York Giants, he had more errors than the moderns, but field conditions were quite different.

Hamner had great range and a gun for an arm, but for some inexplicable reason never was very steady on routine plays. Again, comparisons make it too close to call. Let the fans of each generation claim his man was the best at that difficult post.

Willie Jones was a third baseman with soft hands, and accurate arm, good power at the plate, and an ability to draw walks. However, when comparisons are made, it must be noted that Mike Schmidt did all of those things, and most of them better. Schmidt also had excellent speed, and area where Willie was sadly lacking. The answer is simple, one was good, and the other great.

The early conquerors split the job between Milton Stock and Bobby Byrne, both journeyman types. Stock was a trivia item, being the father-in-law of Eddie Stanky, but there really is no contest for the hot corner vote.

Selecting the outfield is a much tougher task. Taking them chronologically, Dode Paskert, Richie Ashburn and Garry Maddox were all excellent center fielders, the latter two truly superlative.

Maddox' magnificent range make him an automatic Gold Glove recipient, but the nod here goes to Ashburn, a two-time batting champion who, between his hits and walks, virtually lived on base.

Manager Pat Moran in 1915 had a true power hitter in right field. Gavvy Cravath was the king of the dead-ball era, tying or leading the league in homers six times.

His 24 homers in 1915 was the most hit in the majors in this century until Babe Ruth and the live ball came along. Although a righthanded hitter, Cravath perfected the knack of swing late and hammering baseballs over the cozy right field fence at Baker Bowl.

Del Ennis was a solid long-ball threat for the team managed by Eddie Sawyer. Often hooted by the Shibe Park crowd for his seeming nonchalance on defense, Del was one of the most consistent run-producers of his day. Greg Luzinski ranked with his predecessors for several years, but in the last two campaigns has had problems. Basing the vote strictly on the respective championship seasons, make it a tie between Cravath and Ennis, each who won the RBI crown in leading their teams to titles.

Bake McBride, who had his best year, snares the remaining ballot. Dick Sisler, who delivered the pennant-winning homer in 1950, did have his best year of a modest career, but in actuality was a first baseman pressed into outfield service because of Waitkus' comeback. Beals Becker closed his eight-year career with an unimpressive .246 average in 1915.

Summing up, give the current champs a big margin at three infield positions, and a narrow edge behind the plate and in one outfield slot. The Whiz Kids take centerfield, and share another outfield position with the 1915 titans. Shortstop is a three-way tie. Pitching, because of the major role relievers now play, is puzzling to evaluate. All had great talent; none had exceptional depth. Let's call it too tough to rate.

The team of 1980 can do one thing its predecessors didn't. That is win two in a row.

Phillies won when it counted most

By Rusty Pray of the Courier-Post

It is not difficult discovering how the Phillies reached their first World Series in three decades.

They won the National League's East Division by staging a classic run through the stretch, sprinting through September to catch and pass Montreal.

The Phillies won the National League pennant in equally dramatic fashion, nudging aside the game Houston Astros in five after losing two of the first three games of the playoffs.

Indeed, the "how" of the Phillies 1980 season is simple, a straightforward proposition of winning when it counted most.

Why the Phillies are in the Series is another matter entirely, and not nearly so easy to delineate.

If you want to crack open the shell of 167 games and get to the meat of 1980, you must first accept the fact that it is impossible to pigeon hole this 1980 Phillies team. Put the Phillies under a microscope and what you see is a series of "buts" dividing the core like so many reproducing amoebae.

The Phillies are a power team, but their power was generated almost exclusively by one man. The Phillies are a team with speed, but that sword was removed from its scabbard only on occasion.

The Phillies are a team of good pitching, but only because two of their pitchers had super-human years. And, the Phillies are a team of superb defense. But the defense consistently made fundamental mistakes.

In short, the Phillies of 1980 are a team of paradox, a team that sometimes won because of its talent, sometimes despite it.

The year began with a mandate from management- win or else. For the veterans of the club, the players who had failed to reach the World Series in 1976, '77 and '78, this would be their last chance.

Manager Dallas Green, who stepped from a front office job to assume the field position in August of 1979, made it clear that this season was the last chance for many of the veterans. He had the blessings of both owner Ruly Carpenter and General Manager Paul Owens.

"The nucleus of players never reached the potential that was expected of us," said reliever Tug McGraw. "Now, time is passing that nucleus by... We want to win this thing before it's too late."

Time, indeed, was pressing hard upon this team. Of the eight players in Green's opening day lineup, only two- second baseman Manny Trillo and left fielder Greg Luzinski- would not see their 30th birthday before the end of the season. Both are 29.

Catcher Bob Boone is 32; shortstop Larry Bowa 34; center fielder Garry Maddox turned 31 in September; right fielder Bake McBride is 32; first baseman Pete Rose is 39, and third baseman Mike Schmidt turned 31 in September.

"If the guys we have aren't good enough to win it, I don't know how long we can wait for them," Green said many times.

If there was a sense of urgency of purpose to this team it seemed apparent in the early months of April and May. They hit .282 with 32 home runs in May, with Schmidt batting .305 with 12 homers and 29 RBIs. Luzinski hit .321 with eight homers and 18 RBIs and McBride hit .330 with three homers and 23 RBIs.

Their pitching was equally awesome. Lefthander Steve Carlton, who finished the season with a 24-9 record and is the odd-on favorite to win his third Cy Young Award, went 6-1 with a 1.65 earned run average and 70 strikeouts in May. McGraw and righthander Ron Reed came out of the bullpen to combine for three wins, four saves and an ERA of under two.

But then came June and July. And it became apparent that the Phillies were just as capable of finishing fourth- their final standing in 1979- as first.

Luzinski was the most serious casualty of the middle months. He hit .177 in June and .158 before injuring his knee July 5. He would undergo surgery and not return to the team until mid-August.

The list, however, included more than one name. Boone, obviously troubled by off-season knee surgery and his duties as National League player representative during the strike-threatened days of May, hit .226 and .218 in June and July. Schmidt tapered off to .244 and .231. Bowa hit .200 in July after a respectable .286 in June.

And the pitching was in a shambles. Righthander Larry Christenson had undergone elbow surgery and would not pitch again until late August. Righthander Nino Espinosa, who developed bursitis in his shoulder the previous September, never recovered. Lefthander Randy Lerch was totally ineffective.

So the Phillies muddled through the mid-term months with a rotation that included Carlton, righthander Dick Ruthven and whomever happened to be available.

Still, they hovered insistently within striking distance until Aug. 10, a date which marks both the beginning and the end. It was the nadir of the season in terms of winning. But it was the fulcrum upon which the entire year turned.

The Phillies lost both ends of a doubleheader to the Pirates, their third and fourth straight of a lost weekend, and fell six games off the pace.

Between those Sunday games, Green screamed at his team in a tirade that pealed paint from the clubhouse walls. He accused the players of quitting and challenged their desire.

The results of Green's sorcam therapy speak speak for themselves. The Phillies left Pittsburgh and took two of three from Chicago, then swept five from New York. They were 36-19 from that day on, moving into first place less than a month later.

The season, however, was hardly history. They lost the last three games of their final West Coast trip and were in second place, behind Montreal, on Sept. 7. For what remained of the season, the Phillies would occupy first place alone only seven days.

It would be patently unfair to recount 1980 without mentioning some of the rookies Green sprinkled throughout his roster.

There was, first, Lonnie Smith, who substituted sensationally for Luzinski in left. Smith hit .339 and set a club rookie stolen base record with 33. Keith Moreland served well as Boone's backup and as the club's No. 1 right-handed pinch hitter. Moreland hit .412 as a pinch hitter and the club's record was an impressive 22-10 in games he started.

There was, also, righthander Bob Walk, who was called up from the minor leagues to replace the injured Christenson in the rotation. Despite limited experience, Walk won eight of his first nine decisions and brought stability to a staggered staff.

And there was Marty Bystrom with other prospects called up from Oklahoma City, the Phils' Triple-A affiliation, on Sept. 1. Bystrom won all five of his September starts and went 20 innings before allowing a run.

The final drive, however, belonged to the veterans. McBride hit .350 and finished the season at .309 with a career-high 87 RBIs. Schmidt hit 12 home runs and drove in 23 runs. Bowa hit .272 and Trillo emerged from a 3-for-59 slump to hit .317 over the final 15 games en route to a career-high .292 average.

Luzinski, restored to the lineup in August, struggled at the plate. Nevertheless, he delivered clutch hits that tied games, won them, and put the Phillies in the lead.

McGraw was nothing short of awesome, going 5-0 with five saves and a 0.33 ERA. After the All-Star break, McGraw allowed only three earned runs. An incredible figure in September, he permitted one.

Overall, the Phillies were 23-10 from Sept. 1- Oct. 4. They went 12-3 in one-run games, 5-0 in extra innings.

"We played," said Green, "one of the greatest Septembers in history. Talk about playing with your backs to the wall. Our backs were to the wall almost the entire month. We had to win almost every time we went out there."

They had to win two of three games in their final climatic series of the season at Montreal. Earlier in that last week, Green had benched Luzinski, Boone and Maddox in an offensive shakeup.

The move created serious controversy. Bowa publicly criticized the move. Maddox suddenly remembered a finger injury. Green accused some of his players, again, of not wanting to win.

Yet, the Phillies took the first game, 2-1, when Schmidt homered and hit a sacrifice fly. McGraw saved it for Ruthven by striking out five of six batters.

The second game was straight out of Ripley. The Phillies fell behind early, 2-0, scratched out a run then went ahead, 3-2, in the seventh on a two-run single by Luzinski.

In the same inning, Trillo dropped a pop up- one of five Phillies errors- to gift wrap two unearned runs for the Expos. But Boone tied it with two out in the ninth, then Schmidt rapped his 48th home run- a major league record for third baseman- in the 11th to clinch it.

Afterward, Schmidt, who finished the year with 121 RBIs, acknowledged that a division title was not enough. "There's a bigger hill for us to climb," he said.

Added Boone, "We through it all never lost sight of the ultimate goal, found a simile in that bizarre final game.

"This game was like the season," he said. "It didn't look like we were going to win it because we didn't do the things we're capable of doing. We didn't do it very well until it got to the end. That's when we did it. That's the bottom line."

Indeed, the Phillies had to reach the top to get to the bottom. That may be contradictory, but it is true of this particular Phillies team, a team of paradox.

MVP Award becomes more meaningful to Schmidt nowe

By Hal Bodley, Gannett News Service

PHILADELPHIA – When Mike Schmidt was a little boy growing up in Dayton, Ohio, his grandmother encouraged him to play baseball.

In fact, as it became obvious he was gifted in this sport, she became his most important fan, a motivating force that encouraged him and, at times, pushed him.

Viola Schmidt died of cancer on Sept. 26 at age 75 on the eve of Mike's 31st birthday.

"She had been hanging on for a long time, and I think that was because of her interest in my baseball career," Schmidt said. "I had been thinking about her a lot lately – she had been in the hospital 54 days. I would like nothing better than to win that award for her. I had hoped she would hang on and see it happen, but even now it would mean a great deal to me to win it."

"That award" is the National League Most Valuable Player designation. The Phillies' third baseman is a leading candidate for the honor.

He talks openly about it and how much winning it would mean to him. He lead the majors in homers with 48 and led the league in runs batted in with 121, total bases with 342 and slugging average at .624. He finished near the top in runs scored with 104 and his .286 batting average was 31 points above his career mark. He had 17 game-winning RBIs.

"If I win MVP, it will be the biggest thrill of my life," Schmidt said. "It's the ultimate individual award. MVP means a lot of guys around you- you know, you could chop up the trophy and give it to a lot of people in the lineup- have helped you.

"I think if a power hitter can hit over .270, that means he has been relatively consistent most of the season. And I think I have been very consistent this year. Sure, I've had my 0-for-20s and struck out three times in a few games, but I've been able to cut down on my hitless games.

"Really, though, I think my maturing into a better hitter and developing more consistently good techniques as a hitter are the reason for the year I'm having.

"I think learning to hit the ball straight away, not just having to rely on the ball from the middle of the plate in to hit home runs, has made the difference."

Deep down, however, Schmidt is most proud of the fact people are looking at him now as a player who can come through in the clutch.

On the surface, he projects the image of an emotionless, almost I-could-care-less individual. Teammates have been calling him Captain Cool for years.

"I want to always convey to my teammates and to the opposition that I am under control of myself," he said, trying to defend his image.

"I don't want anyone to think I am intimidated by anything that goes on on the field, whether it is being done well or poorly. I like to always keep the opposition feeling I am under control of myself, especially offensively.

"It may appear to some I just go up there and whale away at the ball, but I don't. I try my best to hit, according to the game situation. Obviously, it we're in Wrigley Field, there's no time I could ever go up there and not think home run. I probably get as many homers there as I do singles, but in other parks the situation is different. If we're down 3-0, there's no reason for me to go for a home run."

One vote here for Royals to win easily

By Dick Young, Gannett News Service

NEW YORK – Anybody who has been watching the National League play ball lately has to pick the American League to win the World Series. I can't remember having seen so such shabby stuff pass for big league baseball. Maybe it will change overnight. Maybe the Nationals will say to themselves, hey, fellows this is the big time we're in. They had better, or the Kansas City Royals will blow them out.

I picked the American League to win the World Series long before I knew who'd be playing. I simply think they're playing a better brand of ball. I don't know why that should be. For most of my lifetime, it was the National that executed well, beat you with basics, with style. The American, when they beat you, did it with muscle. The home run. They'd make mistakes, then make you forget it with a shot into the seats. The Nationals would hit-and-run, steal, work a pickoff, turn a double play; heady stuff.

Suddenly, the roles would seem reversed. The Royals played top-notch ball in blowing away the Yankees. They look like a textbook team. The NL playoffs looked like a Punch and Judy show. I expected that any minute the kids from Taiwan would trot out. It looked like the games were being played in Williamsport, home of the Little League World Series.

It started weeks ago, down the stretch of the regular season. I saw the Phils, Pirates and Expos battling each other for the privilege of not making the playoffs. The Expos and Pirates won, so Philly got stuck with the job.

The National playoffs haven't been any improvement. Including the umpiring. It only goes to prove that the umpires can go into a slump like anybody else. This was an elite crew of umps, the cream of the staff, assembled from other groups for the big playoff set. They turned out to be a debating society. I'm not going to second-guess Doug Harvey on the triple-play call that turned out to be a double-play compromise. I guess I watched the replay 10 times, backwards and forward, from different angles, just as you probably did, and I wouldn't bet my house on whether Garry Maddox' Little League pop to the mound was caught or trapped by pitcher Vern Ruhle. The only thing proven by the TV tapes is that Pete Rozelle is right when he says technology has not yet come up with anything that convinces him replays should be used to settle disputes in NFL games.

There was a play later on, however, which was called an out by Bruce Froemming, and was pretty clearly a trapped ball. Bruce Froemming is one of the strong umps in the NL. He hustled down the line to be in position for the call in right, and he hustled too much. He called it on the run. He should have come to a fast-step stop and set himself to make the call. A man's vision blurs when he tries to focus on the run.

That's in the past. Now we look ahead to the big show. There is a certain freshness to this World Series. The last time Kansas City was in this position it was in the International League.

I suppose it would be considered cutesy to say it still is, coming from the AL West as the Royals do. The AL West is considered by most baseball men to be the weakest of the big league divisions. Maybe that's so, but keep in mind that the Royals dominated the AL Eastern teams in head-to-head play. On the final day, the Royals were 14 ahead, and breezing. They were 20 ahead on Aug. 31, with 31 games to play, when somebody said, what are we killing ourselves for? Jim Frey, riding them like Willie Shoemaker, eased up, then got his entry back in stride during the final week, just in time to have them sharp for the Yankees. You have to be a good team, in any division, to be 20 ahead with 31 to go, and you have to be good to take the Yankees in three straight. Anybody who watched that playoff knows he was seeing a fine ballclub.

In an obtuse way, a ghost of the Yankees goes into the World Series. Charley Lau, the Yanks' batting coach, shaped the hitting habits of George Brett and Hal McRae, two top offensive weapons in the Royals' attack. Both men gladly admit it.

"I can remember when it was," says George Brett. "I was hitting .200 at the All-Star break in '74. Charley came over to me and said, 'You can laugh all the way to the bank, just getting hits to leftfield.'"

When a man puts it that way, says George Brett, you have to listen. "Charley said he saw three things in my hitting that he could change to make me improve.

"I was holding my bat the way Yastrzemski did, cocked, which I couldn't handle. I was trying to pull everything. I was up on the plate with an open stance. He moved me off the plate, closed up my stance, and told me to concentrate on hitting the ball from second base to the leftfield line."

Since then, Brett explains, he has grown stronger and pulls for the seats when he gets the right pitch at the right time. "I'm a situation hitter now," he says.

Says Hal McRae: "Charley Lau is the best batting coach in the business. There is nobody close to him as far as teaching ability is concerned."

Most hitting instructors, according to the KC designated hitter, tell you to watch the ball and be aggressive, the way a doctor will tell you to take two aspirin and go to bed.

"Shoot, I heard that stuff when I was a kid," says McRae. "Old men talking across a checker board talk like that. Use your hand, they tell you. They don't tell you when to use your hands."

Charley Lau, batting coach, left the Royals in '78 to join the Yankees. During the playoffs, Charley Lau was careful not to say more than hello to George Brett and Hal McRae. The reason is obvious, but Hal McRae said it anyway at Sunday's practice: "We're reluctant to talk to him in front of people during the regular season or the playoffs, because if we're seen, right away they're going to think we’re talking."

Phillies’ futile past efforts, K.C. past… set stage for matchup of like teams

By Bob Matthews, Gannett News Service

Philadelphia is coming off the first winning post-season series in the long history of the franchise. The Phillies have appeared in two previous World Series (1915 and 1950) with the grand total of one win in nine games.

Kansas City is a first-time starter after knocking off the New York Yankees for the first time in four playoff tries.

The Phillies and Royals are similar in many other ways. Both teams have a potent offensive mixture of power and speed. Each has a 20-game winner and a bullpen ace. Each has a third baseman who figures to be his league's Most Valuable Player. Each thrives on artificial turf.

Both managers are in their first full season.

The individual matchups:

FIRST BASE – Kansas City's Willie Aikens (.278, 20 HRs, 98 RBIs) started slowly but finished fast for a big offensive year. Philadelphia's Pete Rose (.282, 1, 64) has less power but runs faster, fields better and has a history of coming up roses when the spotlight is on. Slight edge to Philadelphia.

SECOND BASE – Philadelphia's Manny Trillo (.292, 7, 43) is one of the few second basemen in the majors who can field with Kansas City's Frank White (.264, 7, 60), and he's a slightly tougher out. White runs better. Even.

THIRD BASE – Kansas City's George Brett (.390, 24, 118) and Philadelphia's Mike Schmidt (.286, 48, 121) both had awesome years at the plate. When the situation calls for a long ball, Brett is as dangerous as Schmidt. Both are underrated fielders and run well. Slight edge to Kansas City.

SHORTSTOP – Kansas City's U. L. Washington (.273, 6, 53) can do more things offensively than Philadelphia's Larry Bowa (.267, 2, 39). Bowa gets points for experience and a steadier glove. Even.

LEFT FIELD – The best leadoff man in the majors is Kansas City's Willie Wilson (.326, 3, 49). When he gets on base, he often steals (79 for 88) and usually scores (134 runs). Defensively, he's a center fielder playing left. Philadelphia's Greg Luzinski (.228, 19, 56) has struggled with the bat ail season. Rookie sub Lonnie Smith (.339, 3, 20) has less power and much more speed (33 stolen bases). Both are weak defensively. Solid edge to Kansas City.

CENTER FIELD – Philadelphia's Garry Maddox (.259, 11, 73) slipped in all departments this unhappy season. He's a super glove with a nasty habit of botching plays at the worst possible times. Kansas City's Amos Otis (.251, 10, 53) is fading, too. He ll never run into a wall or get a hit off a power pitcher, but he's still a resourceful base runner (16 steals in 17 tries). Edge to Philadelphia.

RIGHT FIELD – Philadelphia's Bake McBride (.309, 9, 87) is a dangerous all-around player with the talent to turn a World Series around. Kansas City's platoon of John Wathan (.305, 6, 58) and Clint Hurdle (.294, 10, 60) hits well but can't match McBride in the field. Edge to Philadelphia.

CATCHER – Kansas City's Darrell Porter (.249, 7, 51) is capable of better things after a disappointing year. Wathan is an excellent backup. Philadelphia's Bob Boone (.267, 2, 39) has a bad foot and his production has suffered, but his experience gets the starting nod over Keith Moreland (.314, 4, 29). Slight edge to Kansas City.

DESIGNATED HITTER – Kansas City's Hal McRae (.297, 14. 83) is a professional designated hitter and one of the toughest outs alive. Philadelphia figures to fill the spot with Luzinski. Smith or Del Unser. Edge to Kansas City.

STARTING PITCHERS – Philadelphia's Steve Carlton (24-9, 2.34 ERA) is by far the best starter on either team. The other Phillie starters include Dick Ruthven (17-10), Larry Christenson (5-1) and rookie Marty Bystrom (5-0). The only lefty is Carlton. The Royals could have fun against the others. Kansas City's starters figure to be Dennis Leonard (20-11). Larry Gura (18-10). Rich Gale (13-9) and Paul Splittorff (14-11). Because of Carlton, slight edge to Philadelphia.

RELIEF PITCHERS – Philadelphia appears to have more bullpen depth. The long men are rookie Bob Walk (11-7) and Dickie Noles (1-4). Warren Brusstar (2-2) and Ron Reed (7-5) are the righthanded short men. Kevin Saucier (7-3) is the ordinary lefty short man. Tug McGraw (5-4. 20 saves, 1.47) is the extraordinary lefty short man, but he could be fatigued after his heroics in the playoffs the past week. Kansas City is weak in second-line pitching. Rene Martin (10-10) is the best bet in long relief. Marty Pattin's roundhouse curve doesn't fool hitters for long. Ken Brett and Jeff Twitty are your basic mop-up men. No wonder Dan Quisenberry (12-7, 33 saves, 3.09) keeps so busy. Edge to Philadelphia.

HITTING – Both teams rely oh speed and power to manufacture runs. Kansas City scored 809 runs with a .286 team average and 115 home runs. Philadelphia scored 728 runs on a .270 team average and 117 homers. Kansas City's advantage in team average is slightly misleading since the Royals used the DH rule all season while the Phillie pitchers hit for themselves. Even.

PITCHING – Philadelphia's staff ERA was 3.44, with eight shutouts. The Phillies allowed 1.419 hits and struck out 889 in 1.480 innings. Kansas City's staff ERA was 3.85 with nine shutouts. The Royals allowed 1,496 hits and struck out 614 In 1,459 innings. Kansas City was facing DHs all season. Slight edge to Philadelphia.

FIELDING – Both teams are solid. Kansas City has a big edge in left field. Philadelphia has a slight edge at three spots: center field, right field and first base. Best bets to throw a game away are Schmidt (27 errors) and Washington (31 errors). Even.

TEAM SPEED – Kansas City loves to intimidate the opposition, stealing bases and stretching hits. Wilson sets the pace (79 steals), but teammates Washington (20), White (19). Wathan (17). Otis (16), Brett (15) and McRae (10) all can and will run. The Royals stole 185 bases and were caught 42 times. The Phillies stole 140 bases and were nabbed 62 times. Smith led the way with 33 steals, followed by Maddox (25), Bowa (21), McBride (13), Schmidt (12) and Rose (12). McBride is capable of much more. Slight edge to Kansas City.

BENCH – The best sub on either team is Kansas City's Wathan. The most experienced infield sub is former all-star Dave Chalk of the Royals. Philadelphia has two classy lefty bats in Greg Gross and Unser. Rookie Moreland can hit. The team's top infield reserve is Ramon Aviles. Even.

OTHER FACTORS – Kansas City comes in fresh and cocky after sweeping the Yan kees. Philadelphia comes in pooped and can't be ecstatic over being extended to five games by undermanned Houston.

The Royals outscored the opposition by 114 runs this season. The Phillies outscored the opposition by 89.

Kansas City is 51-32 at home and 49-33 on the road. Philadelphia is 50-33 and 44-40.

Kansas City's lack of solid lefty relief pitching might not be disastrous against Philadelphia's predominantly righthanded attack.

Philadelphia comes in with some tired pitching arms after a grueling series against Houston.

SUMMARY – A terrific matchup. The strengths, weaknesses and style of play of these teams are remarkably similar. Prediction: The Royals in six because it is George Brett’s year.

McGraw philosophy matches personality

By Rusty Pray of the Courier-Post

PHILADELPHIA – He had been known to appear dressed in Army fatigues before a game, playfully squirt fans with water and orchestrate cheers while striding from the pitcher's mound.

He is an acknowledged master of the art of catching popups behind his back.

He goes about his life as a relief pitcher according to a "frozen snowball" philosophy.

And his best pitch, the screwball, could well serve as a personality profile.

He is Frank Edwin McGraw, known more widely as simply Tug.

And he is one of the primary reasons why the Phillies are in the World Series.

McGraw, the lefthanded reliever who coined the slogan "You Gotta Believe" while leading the New York Mets to one of their two pennants, has, at age 36, emerged this season as one of baseball's most valuable fireman.

He completed the regular season winning five games and saving 20 others. In 92 and one-third innings, he had allowed a miserly 62 hits and 15 earned runs. His earned run average was a stunning 1.47.

"Without Tug we're not anywhere, let's face it," Manager Dallas Green said. "He's been in the bullpen. He's been Mr. Consistency and Mr. Clutch.

"We have been kind of sporadic in terms of our bullpen. We'd get a good performance from one guy a couple of times out, then the next couple he's not there. You can't win pennants that way and you can't shut games down that way."

Green knows whereof he speaks.

The Phils went into 1980 with serious questions concerning their bullpen.

McGraw, who was coming off a year in which his ERA had ballooned to 5.14 and had tied a National League record by permitting four grand slams, was mentioned more than once as possible trade material.

His age, his mediocre 1979 statistics and the uncertainty that surrounded the entire pitching staff all pointed toward him pitching for some other team this year.

But the trade never materialized, making it one of the best deals General Manager Paul Owens never made.

"I am having a good year," McGraw allowed. "The first week of the season I struggled a little bit- as most pitcher do – but I've been consistent since then."

Indeed, he has been nothing short of sensational since returning from the disabled list on July 17.

McGraw had developed tendonitis in his left arm from experimenting with his delivery. (His normal delivery is direct overhand).

"That is the logical reason why I hurt my arm, so we'll put it (throwing sidearm) away until about '85," he said after rejoining the Phillies.

Mostly, McGraw has been putting opposing hitters away.

In the month of September, while the Phillies were battling Montreal for first place, McGraw recorded four wins and saved three games. In 26 innings, he did not allow a run. After coming off the disabled list July 17, McGraw's stats were incredible: 5-1 record; appeared in 33 games; pitched 52 1/3 innings, allowed three earned runs; had 46 strikeouts; had 13 saves and an 0.52 ERA.

Since returning from the disabled list, he fashioned an 0.58 ERA during the course of 30 appearances.

"I think our team has been very confident when Tug comes in a game (because) we're going to shut the other team down," Green said. "It's up to them, then, to score."

McGraw's attitude has been perhaps as important to the Phillies as his pitching.

He is a breath of fresh air in a clubhouse that often is as stuffy as an executive meeting room.

His is an emotional personality on a team seemingly afraid to show its emotions.

"The more able you are to learn to accept the consequences of what happens after you throw the ball, the more successful you're going to be and the fewer failures you're going to have."

McGraw was unable to accept the consequences of a pitch he threw to Los Angeles' Joe Ferguson in August.

It was supposed to be the second ball of an intentional walk, but he got it too close to the plate and Ferguson punched it into right field for a two-run single. He was so incensed he threw at the next hitter, Bill Russell, who charged the mound and touched off a bench-clearing brawl after he was hit by McGraw's fourth attempt.

McGraw later publicly apologized for his actions and showed up at a game in Dodger Stadium wearing a green Army outfit.

He was, he explained, trying to camouflage himself from any grudge-carrying Dodger fans.

"If you can't laugh at yourself once in awhile and use that as a tool to accept failures, then you're going to continue to have more and more failures and you're going to be out of the game," he said.

"It's that 'Frozen Snowball' theory I came up with a few years ago. Basically, it's a humorous way of describing an approach to the game."

And according to McGraw, it goes like this: "Science has proven that in 50 billion years the sun is going to exhaust its energies, and the earth is going to freeze over and orbit through space, taking on the appearance of a frozen snowball.

"When that day comes, who's going to give a damn whether Andre Dawson hit a home run off me, or that I gave up four grand slams last year?"

Best Brett awaits rare phone calls

By Will Grimsley, Associated Press

When the World Series gets under way tonight and attention is focused on Kansas City's George Brett, the best hitter in all baseball, you might spare a look out in the Royals' bullpen.

There you will catch a near carbon copy of the stocky, blond slugger- sitting on a bench, snuggly wrapped in a wind breaker, a loose glove at his side, a man waiting for a telephone call that rarely comes.

The other Brett.

He is Ken Brett, 32, journeyman pitcher, veteran of 14 major league seasons with nine different clubs in both leagues, a reliever hanging onto his career by his fingernails.

"George?" Ken Brett repeated the name. "He knows I can whip his butt anytime."

That's the way big brothers talk about little brothers. The language sounds harsh but it is laced with love and admiration.

"There were four of us brothers," explained Ken. "George, 27, is the youngest. John, 34, is in the construction business and Bobby, 30, is in real estate, both in Los Angeles."

The all look alike with their athletic physiques, heads of bushy hair, laughing blue eyes and pleasant dispositions.

"I never thought George would be much of a ballplayer," said Ken. "He was just average in high school, pretty good in football. But my dad, who was a good judge, always said George would be a great one."

At this point, Bobby, the neutral brother, put in his two cents worth.

"Ken was by far the best athlete in the family," he said. "George wasn't even the best player on his high school team. Ken was rated the best high school prospect in the country. He was great in basketball and football as well."

Then what went wrong with the older Brett?

"My first year in the majors I suffered an arm injury," Ken Brett explained. "I never got as good as I should have been."

Ken broke in with Boston in 1967 and at age 19 become the youngest pitcher ever to appear in a World Series, making two relief appearances against the Cardinals without giving up a hit.

His "Have Suitcase, Will Travel" career took him to Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, New York Yankees, Chicago White Sox, California, Minnesota and the Los Angeles Dodgers before winding up in late August as a Royals teammate of brother George.

"I hurt my arm in the spring and the Dodgers gave me my release," he said. "I did nothing from April through June. I planned to quit baseball. I took some job tests and found out I was good for nothing besides baseball.

"Then the Royals gave me this other chance. I wish I could pitch more. I think I could help."

Ken Brett, 5-10, 190 pounds, a left-hander, had his best seasons with the 1973 Phillies and 1974 Pirates with 13-9 records.

Jim Frey no longer a "nobody"

By Warren Mayes, Gannett News Service

PHILADELPHIA – A few months ago, Jim Frey was eminently qualified for the title of "The Man Nobody Knows."

The rookie manager of the American League champion Kansas City Royals had spent three decades in a baseball uniform.

But the first 29 years were spent in the minor leagues and later as one of the legions of ex-ballplayers whose loyalty is rewarded with a job as a coach.

He toiled for 15 years in the Baltimore Orioles' organization as hitting instructor, in the bullpen and as a first-base coach. With flamboyant manager Earl Weaver around, Frey never enjoyed much of the limelight.

But he gets his chance this week as he leads the Royals into the club's first-ever World Series tonight against the Philadelphia Phillies.

Despite the avalanche of attention and the pressure of the event, Frey has retained his low-key sense of humor, particularly about his past.

"All I did in Baltimore was hit ground balls to the infield," he said. "I didn't think that really was a good qualification to manage."

While growing up in Cincinnati with his childhood buddy, Boston manager Don Zimmer, he focused his attention on baseball. His preparation continued through his 14 years in the minor leagues where he accumulated a .302 lifetime batting average.

"I thought – at that young age – I'd get a chance to manage. A lot of guys like me think the same thoughts but never get to do it.

"The big question is who will hire you when nobody knows Jim Frey. Nobody ever thought of me. Nobody knew me."

Well, almost nobody.

After Whitey Herzog was fired as the Royals' manager after the 1979 season, Frey's name was suggested by several people including front-office executives Frank Cashman of the New York Mets and Harry Dalton of the California Angels.

Joe Burke, the Kansas City general manager, took their advice even though he had never met nor heard much about Frey.

"I had to be introduced to Jim," Burke said. "But the thing that I saw from him the first day was the way he used the word 'we'- even before he was hired. He sold himself to me at the first meeting."

While Herzog's brash style had spawned controversy and some dissent along with three division titles, Frey began his first season determined to be up-front and open with his new players.

More than one player was startled in spring training when he stuck out his hand and said, "I'm Jim Frey, the new manager. Glad to meet you."

He has coupled his subtle humor and low-key style with a liberal dose of togetherness in leading the Royals to a runaway title in the American League's Western Division.

Diary of Phils' trip to the Series

By Helene Gormley of the Courier-Post

Glimpses along the road to the Phillies' first National League pennant in 30 years:

April 11: Greg Luzinski hits emotional three-run home run in his first at bat to send Phillies and Steve Carlton on to a 6-3 victory over Expos before second largest opening-night crowd (48,460).

April 12: Three hits each for Garry Maddox, Manny Trillo as Dick Ruthven wins first with save for Tug McGraw, 6-2 vs. Expos.

April 16: Carlton gets second win as Phillies score six in 9th for comeback 8-3 victory over Cardinals.

April 18: Mike Schmidt and Luzinski homer back-to-back, but Expos prevail, 7-5.

April 19: Bake McBride drives in four, Larry Christenson wins first, 13-4, in Montreal.

April 22: Following a pair of defeats, the Phillies rally to bomb Mets 14-8; Schmidt hits two homers, including grand slam, and drives in six.

April 26: Carlton sets modern National League record with his sixth one-hitter (Ted Simmons single to start the second inning). Steve also becomes the 10th pitcher to reach 2,700 strikeouts.

April 30: Month ends with 6-9 record. a second straight loss to Mets' Bomback.

May 1: Carlton wins fourth, 2-1, in New York on Luis Aguayo's two-run homer, his first in the majors.

May 2: Greg Gross has key two-run pinch single in 9-5 win over L.A.

May 3: Schmidt and Luzinski homer for second straight game and Phillies beat Dodgers again, 7-3.

May 5: Two homers by Schmidt help Carlton win 5th. Steve loses no-hitter on Bill Nahorodny's single with two out in eighth, longest Carlton has gone in a no-hit bid.

May 6: Schmidt drives in four, Ruthven evens record at 2-2 with 10-5 triumph over Atlanta.

May 11: Pete Rose steals second, third and home in 6th inning as Phillies salvage one game of a three-game series in Cincinnati, 7-3.

May 14: Rose drives in four, Carlton wins sixth as Phillies gain split in two-game series in Atlanta.

May 16: Ruthven blanks J.R. Richard and Astros, 3-0, in the Dome.

May 17: Christenson night against the Astros. He homers with two on and runs his record to 3-0.

May 19: Carlton wins seventh game with 6-4 decision over Reds.

May 20: Two homers by Luzinski, one each by Schmidt and McBride wasted as Reds gain 7-6 win.

May 21: Luzinski homers, drives in three, Keith Moreland and Ramon Aviles add first major league home runs and Ron Reed earns second win in relief as Reds fall, 9-8.

May 23: Carlton takes major league lead in wins, strikeouts with four-hit, 3-0 win over Houston.

May 24: Kevin Saucier adds second relief victory with 5-4 win over Houston as Phils move to within two games of first-place Pirates.

May 25: Maddox, Schmidt and Luzinski homer to power Ruthven and Phils to 6-2 sweep of Astros. One game out.

May 26: Larry Bowa's single plates two ninth-inning runs as Phils edge Pirates, 7-6, to take over first place in a game which featured a brawl after Saucier hits Bert Blyleven.

May 27: Five-game win streak ends as Pirates win, 3-2, in 13 innings.

May 28: Randy Lerch wins first of season as Phils move back into first place by .004 after 6-3 win over Pirates.

May 31: Ninth win for Carlton and two more home runs by Schmidt in his favorite park Wrigley Field, as month ends with 17-9 record.

June 1: Bad start of new month with loss in Chicago, two in Pittsburgh.

June 4: Carlton wins 10th, 4-3, in Three Rivers Stadium.

June 6: Rookie Bob Walk notches first major league win, 6-5 over Cubs.

June 7: Lerch wins second, 5-2 over Cubs, for club's 13th win in 17 games.

June 13: First seven batters hit safely (one shy of record), seven runs scored as Ruthven wins sixth, 9-6 over San Diego.

June 14: Schmidt and Luzinski homer, Carlton wins sixth straight, 3-1 over San Diego, with save by McGraw.

June 15: Million mark reached in attendance as Walk wins second, 8-5 over Pirates.

June 17: Gross delivers game-winning pinch single in eighth for 6-5 win as Reed wins, McGraw saves for second straight game.

June 18: Carlton's seventh straight win, 5-1 over San Diego, moves Phils half-game behind division-leading Expos.

June 22: Carlton puts stop to three-game losing streak, beating Giants, 4-3, as west coast trip ends 4-3.

June 25: Schmidt's 10th-inning single enables Phils to win one of three from Expos.

June 29: Walk wins over Mets, 5-2, to snap four-game Phillies losing streak.

June 30: Moreland's grand slam highlights seven-run fourth as Noles wins first, 7-5, in Montreal. Month ends with 14-14 record.

July 1: Lerch wins third with sterling 10-inning 5-4 win in Montreal. Phils trail by one game.

July 3: Doubleheader sweep in St. Louis follows Montreal loss. Ruthven wins 2-1 over Cardinals in opener, Lonnie Smith (four hits, three runs) and unbeaten Walk (4-0) standouts in 8-1 nightcap victory.

July 6: In final game before All-Star break, Carlton snaps two-game Phils losing streak with 8-3 win over St. Louis. Lefty fans Tony Scott in fourth to become baseball's greatest lefthanded strikeout artist.

July 12: 53,234 witness 5-4 win over Pirates (Saucier wins fourth) as Phils move into first.

July 14: Smith gets five hits, but Phils lose second straight to Pirates, 13-11, as Dave Parker homers twice.

July 17: Carlton wins 15th, 2-1 against Houston. Schmidt, Luzinski and Trillo out with injuries.

July 25: Schmidt breaks Del Ennis record with 260th home run in first inning, adds second homer, double and single to drive in four in 5-4 win over Braves.

July 27: Maddox have five RBIs; Rose, Smith and Bowa have three hits each as Carlton breezes, 17-4, over Braves.

July 29: Maddox 5-for-5, drives in three as Phils rally to beat Houston, 9-6.

July 30: Ruthven beats Nolan Ryan, 6-4; Maddox drives in three, Phils end month 15-14, in third place, three out.

August 1: Walk's record 8-1, with McGraw's save, 3-1 against Reds.

August 3: Nino Espinosa wins, Reed saves, in 8-4 win over Cincinnati.

August 7: Phils end home stand with two-game split against Cards. Carlton wins 17th, McGraw notches 11th save.

August 10: Low point of season, losing all four in Pittsburgh to fall six games back of Expos and Pirates.

August 12: Two big wins in Chicago. Warren Brusstar wins first, 8-5 in 15-inning suspended game; Carlton coasts to 18th win; Schmidt homers in both.

August 14: Espinosa wins 8-1 vs. Mets, Schmidt homers in fourth straight game.

August 17: Phils complete first five-game sweep in 25 years as Carlton wins 19th, Lerch his 4th and Maddox homers in each game. Trip which started 0-4 in Pittsburgh ends 7-5.

August 21: Schmidt hits two homers, Bowa adds inside-the-park home run as Phils edge Padres 9-8 in 17 innings to move into second place.

August 24: Luzinski returns to lineup and hits back-to-back homers with Schmidt for fifth time of season as Ruthven ends two-game losing streak with 7-1 win over Giants.

August 27: Carlton wins 20th to snap two-game losing streak, 4-3 over Dodgers.

August 30: Phils go into first as Ruthven wins again, 6-1, for club's seventh straight road victory. Fall into second after 5-1 loss in second game.

August 31: 10-3 loss to San Diego finds Phils in second, half-game out, as Pirates suffer seventh straight loss and Expos are swept in four games by Dodgers.

September 1: Bob Boone singles in winning run for Carlton's 21st, 6-4 in San Francisco. Phils in first, .535 to Expos .534.

September 3: Ruthven wins fourth straight with McGraw save in sweep of Giants.

September 4: McGraw saves Walk's 10th, Luzinski and Schmidt homer vs. Dodgers.

September 6: Monday hits two-run homer, robs McBride of same, as Dodgers 7-4 win drops Phils to second.

September 8: Luzinski drives in winning run, McGraw wins first win of year 6-2 over Pirates.

September 10: Rookie Marty Bystrom blanks Mets, 5-0, in first major league start to keep Phils half-game behind Expos.

September 11: Del Unser's key pinch double helps Ruthven notch 15th at Shea.

September 13: Phillies acquire Sparky Lyle from Rangers on day Carlton beats St. Louis for fifth time this year, 2-1.

September 17: Maddox steals 2nd, 3rd, and scores winning run on Unser's pinch single in 11th as Lyle notches first save.

September 20: Bystrom's consecutive scoreless innings streak ends at 20, but wins third straight, 7-3, without shutout relief by Saucier, Dickie Noles and McGraw.

September 22: Phils move into first as Moreland's pinch double drives in Bowa in 10-inning, 3-2 win in St. Louis, to put Phils in first. Carlton wins 23rd, Tug saves. Carlton becomes first pitcher to go 6-0 vs. a team in one season since Robin Roberts did it to Brooklyn in 1952.

September 26: McBride's dramatic 9th inning homer beats Expos, 2-1. Phils lead by 1½.

September 28: Gary Carter hits two home runs, 8-3 win coupled with 4-3 win over Carlton on Saturday moves Expos into first.

September 30: Bystrom wins fifth, 14-2, over Cubs. Phillies finish month with 20-9 record in second place, half-game out.

October 2: Walk survives rain delay for win, McGraw gets save, 4-2 over Cubs, for sweep that deadlocks Phils with Montreal.

October 4: Schmidt hits dramatic two-run homer in 11th, McGraw gets the win as Phils win Eastern Division championship.

October 7: Luzinski has two-run homer, Carlton wins 3-1 with relief help from McGraw for 1-0 edge over Houston in playoffs.

October 8: Wasted opportunities, 14 left on base, key Astros 7-4, 10-inning win. Reed touched for four hits, two runs as relief corps fails to throttle Astros.

October 10: Triple by Joe Morgan leading off 11th, bases-loaded sacrifice fly by Denny Walling earns Dennis Smith 1-0 win over McGraw as Astros go up 2-1 in series.

October 11: Luzinski delivers key double, scoring Rose from first, and Trillo doubles in insurance run as McGraw saves Brusstar's 5-3 10-inning win. Series even at 2-2.

October 12: Maddox delivers game-winning double, scoring Unser, and Ruthven hurls two scoreless innings as Phils win pennant, 8-7, in 10 innings. Games marks dramatic five-run rally in eighth highlighted by Trillo's triple. Manager Dallas Green uses six pitchers in clincher.