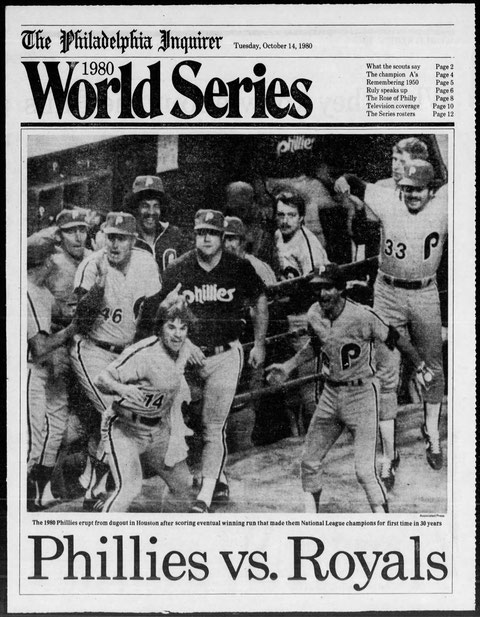

Philadelphia Inquirer World Series Special - October 14, 1980

Photo Album

What they know about the Phils

By Jack Carney, Special to The Inquirer

Somewhere behind home plate at Veterans Stadium you can spot them with their pads in hand and pens scribbling away at a furious pace, taking note of seemingly every move made by every player on the field.

They're baseball advance scouts, nomads by nature who make endless three-night stands in countless cities, charting every nuance of every player for a coming confrontation with their employers, hoping to find a weakness that can be exploited.

For 18 years Earl Rapp did his spying for the Houston Astros, who, until this year, never made it to the National League playoffs. Scouts, like managers, have a way of wearing out their welcome if pennants aren't forthcoming, and Rapp's welcome in Space City, U.S.A., wore out a little more than a year ago.

In one of the ironies of this year's World Series, Rapp found a new home as advance scout for Kansas City. Instead of scouting the Phillies for the team they just defeated in the NL playoffs, Rapp has been taking notes that he hopes will help turn the Royals into world champions.

Rapp has been with the Phillies for three weeks, a period in which they overtook Montreal for the NL East title, then defeated Houston in the playoffs. That they won came as no surprise to Rapp, despite whatever loyalties he still carries for the Astros.

"I just thought the Phillies had the most guns to get there (the World Series)," Rapp said following Game 2 of the playoffs. "As far as I'm concerned, the Phillies' pitching staff is what gave them the edge.

"Their pitching is a lot better than people give them credit for. With (Larry) Christenson OK now, and that kid (Marty) Bystrom throwing the way he is, along with (Steve) Carlton and (Dick) Ruthven, the Phillies have as solid front-line pitching as any team in baseball."

Pitching is just one aspect of what Rapp dissects when he follows a club. When he sends back his report, it enumerates a team's strengths and weaknesses, what to look for from the pitchers and how to most effectively retire the hitters.

"The thing that stands out in my mind the most right now is the way Mike Schmidt was swinging the bat down the stretch," said Rapp. "On top of everything I send back is (that) we can't let Schmidt beat us, no matter who's coming up behind him."

Rapp was obviously referring to Greg Luzinski, who, some argue, determines what kind of pitches Schmidt will see.

"Luzinski has the big reputation for producing when it counts," said Rapp, "but right now I fear Schmidt more than anyone on their team."

Rapp wouldn't display his report that was headed for Kansas City, but he was willing to compare the teams in every department.

"No doubt one of their (Phillies) big strengths is defense down the middle," he said. "It's a mark of all the good clubs, and the Phillies are no exception. There probably isn't a better club in the National League at shortstop, second base, catcher and center field.

"(Larry) Bowa, (Manny) Trillo, (Bob) Boone and (Garry) Maddox are all Gold Glovers, and, if they're not the best at their positions defensively, then they're awfully close to it.

"Those four guys give you such great glove-work their hitting isn't all that important. If you have that kind of defense, you look to get your hitting from the side zones, meaning left field, right field, first and third base, and that's mainly the way the Phillies are."

Following is a position-by-position comparison of the Royals and Phillies by Rapp in what he said was "as objective as I can be about it:"

FIRST BASE "Even though he's just played the position two years, Pete Rose is more than adequate defensively at first base. From an offensive standpoint, our guy (Willie Mays Aikens) is more of a threat powerwise, but Rose is the better percentage hitter. I have to give Rose the edge here."

SECOND BASE "Phillie fans haven't had a chance to see Frank White play, but I'll tell you one thing, he's as good a defensive player as Manny Trillo, and that's saying something. They're both Gold Glovers. I'd say Frank (who, like Trillo, was voted the most valuable player in his league's playoffs) has more range than Trillo, but no second baseman in the game has Trillo's arm. Trillo gets a slight edge with the bat, but, overall, I've gotta call this even. In my way of thinking, these are the two best second basemen in the game."

SHORTSTOP "Larry Bowa gets the edge here, because of his defense. U.L. Washington does a good job for us, but he's a little erratic in the field at times. Bowa is as steady as they come."

THIRD BASE "I was afraid we'd come to this pretty soon. This one is tough to be objective about. In my mind, George Brett is the best hitter in baseball, but to be fair to the Phillies, Mike Schmidt is the best third baseman in the National League. I gotta call this one even, if only because I don't think either team would trade one for the other. But it'd be awful nice to have them both on the same team."

LEFT FIELD "Luzinski's a pretty potent bat to have, but Willie Wilson gets a superior edge here for us. Defensively, it's no contest; Wilson might be the best leftfielder in baseball. Offensively, Luzinski has more power, but Wilson had 230 hits this year and stole over 70 bases. No contest it's Wilson all the way."

CENTER FIELD - "I have to call this one even, too. Maddox is slightly better than Amos Otis is defensively, but not much. Both of them are having off years with the bat."

RIGHT FIELD - "I have to give the Phillies an edge here with Bake McBride, because he's a better hitter and has more speed than either one of the guys we use out there (Clint Hurdle and John Wathan). Plus, Bake's a pretty decent guy with the glove."

STARTING PITCHING "I give the edge to the Phils here with Carlton, Ruthven, Christenson and Bystom, but not by much. Our foursome of Larry Gura, Dennis Leonard, Paul Splittorff and Rich Gale is formidable, too."

RELIEF PITCHING - "Both teams rely pretty much on one main stopper, McGraw for the Phils and (Dan) Quisenberry for us. McGraw had a super year (20 saves), but I still have to give a decided edge to Quisenberry. He led the majors with 33 saves and had 12 wins on top of that. That's a lot of production out of one guy."

DEPTH "We got pretty good mileage out of guys like Jamie Quirk, Pete LaCock and Ranee Mullinix, but it's pretty hard to beat the Phillies' depth with people like (Greg) Gross, Del Unser, and those two young kids, (Lonnie) Smith and (Keith) Moreland. Philly gets the edge here."

TEAM SPEED - "Take away Willie Wilson from our team and I'd say it's even, but with him around, it's a decided edge for us;"

So, who's gonna win, Earl?

"The Royals, no question about it," Rapp said, flashing a big smile. "You didn't really expect me to be objective about that, did you?"

The heaviest hitting team in 30 seasons… the AL champion Kansas City Royals

By Ray Kelly, Special to The Inquirer

OK, you never heard of Dan Quisenberry. Don’t apologize. He’s right out of a dime novel. He’s a pitcher who doesn’t throw hard enough to break the proverbial pane of glass and, come to think of it, doesn’t do much of anything – except get hitters out for the Kansas City Royals.

The Inquirer canvassed a group of major league scouts to find out what the newly crowned American League pennant winners have to offer besides the gifted George Brett.

The opinions were enlightening, but several scouts insisted on remaining anonymous. “I don’t want to put the rap on some player and have him read about it,” one said.

Perhaps the easiest way to get into a rundown on the Royals is to mention that they are, in some respects, similar to the Houston Astros, who lost to the wild National League title series.

Like the Astros, the Royals rely heavily on defense, only the American Leaguers have more players who can do more with the leather. Houston has speed, but not as much as the Royals, who feature Willie Wilson, the leftfielder who swiped 79 bases during the season. Like the Astros, the Royals have quality starting pitchers.

It’s when they head for the bat rack that the Royals shine. Brett, of course, got the whole country stirred up when he made a bid to become the first .400 hitter since Ted Williams. Eventually he settled for .390, which puts him up there with the big boys as a hitter.

But he had plenty of help from Wilson and the rest of the Royals, who completed the season with a team batting average of .286, the highest in the majors in 30 years.

They made a runaway of the American League’s Western Division for the fourth time in five years and feel this team is the best.

Most of the scouts agree this has been a off year for Darrell Porter, the veteran catcher. It figures, considering that he was in a sanitarium at the start of spring training, coping with a drug and alcohol problem.

“Actually, he’s made a remarkable recovery and, while he hasn’t hit as good as expected, he still handles the pitchers and throws out runners the way it should be done,” a scout said.

Willie Aikens, big, strong and coming on, is the Royals’ first baseman. “He’s no fancy-dan around the bag, but he catches the ball. Don’t make any mistakes on him at the plate. He’s got the sock but he uppercuts the ball and can be pitched to,” another scout offered.

The Royals also used Pete LaCock and John Wathan as defensive replacements for Aikens. “Wathan (who also catches and plays the outfield) is a real good utility player and a tough hitter. He doesn’t have power, but he makes contact most of the time.”

At second base, Frank White is quick and covers a lot of ground. “He makes the double-play better than most and is a .300 hitter except when he tries to go for the long ball. He’ll steal a base if you need it,” said a scout.

Tom Ferrick, the Kansas City superscout, said that, “if the Royals go into the World Series with the Phillies, check Brett and (Pete) Rose. We all know about Pete’s hustle, but George is the same way. That’s why he gets hurt so much.”

It’s kind of a roundabout compliment, but some of the scouts peg U.L. Washington as an “AstroTurf” shortstop. “The idea is that there are not many bad hops on the artificial stuff and U.L., with all kinds of speed and quickness, is in his element.”

Washington and Wilson are both switch-hitters.

“It’s important,” said one of the bird dogs. “Those switch-hitters make it tough on a manager who is thinking about a pitching change.”

It is agreed on all sides that the man with the best centerfielder potential in the majors is playing in left for the Royals. That would be Wilson, who, according to the Phillies’ great scout, Hugh Alexander, “outruns fly balls the way Garry Maddox does.”

Wilson also hit .313 for the Royals and they say he’s so fast he even steals bases on pitch-outs.

Amos Otis is the centerfielder. He’s been around for a long time and knows what to do. “He can play, what more can I say?” said another scout.

The Royals prefer to go against a right-handed pitcher since it gives them a chance to use young Clint Hurdle in right field. He hasn’t quite lived up to the buildup they gave him as a rookie. “He still has trouble against southpaws, but he’ll give right-handers fits.”

The veteran Hal McRae is considered one of the best of the American League’s designated hitters and he’ll probably handle that assignment against the Phillies.

“This man has eased into the DH role like it was made for him,” said a scout.

Those who watched the Royals play the New York Yankees in the American League Championship Series had to be impressed by both southpaw Larry Gura and righthander Dennis Leonard.

Gura, an 18-game winner during the regular season, is a blue-chipper. He throws hard enough and has exceptional control. He’ll need it to cope with the predominately righthanded-hitting Phillies.

Leonard is erratic, but he’s got all the pitches and throws his fast ball at better than 95 miles per hour.

Paul Splittorff, another lefty, is a change-of-speed specialist who could surprise the Phillies. He pitches a lot like Tommy John, the Yankees’ veteran who always gave the Phillies trouble when he was with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Oh yeah. There is the other Brett, Ken. The ex-Phillie has been out most of the season with shoulder trouble, but when he’s healthy he’s a tough competitor. And then there is Rich Gale. He’s a hard thrower who tapered off after a strong start his rookie year of 1979 and is now trying to return to form.

Marty Pattin surprised everybody by making himself useful as a “long man” for the Royals along with Renie Martin (from Delaware) and Jim Twitty.

Finally, there is the redoubtable Quisenberry.

The Royals were searching their farm clubs for relief help last summer when they took a chance on Quisenberry. He’s been a revelation ever since.

According to the scouts, Quisenberry’s fast ball has been clocked at 77 m.p.h. But he’s a submariner. He throws underhanded from the right side, and since he’s the only one in the league who resorts to that style, most hitters are uncomfortable facing him.

After two-score and ten, let’s play it again

By Art Morrow, Special to The Inquirer

Times change, and faces, but human nature remains the same. Fifty years have passed since Philadelphia won a World Series, and not many are left who remember the day, but baseball addicts live in hope and dream of the golden moments as they did in 1930.

Philadelphia was a city of baseball extremes then. Connie Mack's Athletics were the best team in baseball and Burt Shotton's Phillies were the worst.

The Phillies fielded a team of .300 hitters: Chuck Klein, Lefty O'Doul, Art Whitney, Barney Friberg, Harry McCurdy, Frank Hurst, John Sherlock and Virgil Davis. But, with, maladroit fielding and a short fence in right at Baker Bowl, the Phillies finished last. They did not win one season's series. They totaled just five victories in April, seven in May and eight in July, they wound up with 52 wins, 102 losses and a percentage of .338.

The Athletics, 4-1 victors over the Chicago Cubs in the 1929 World Series, won 102, and lost 52 for a .662 percentage. The A's had two top sluggers, Al Simmons and Jimmy Foxx; two brilliant pitchers, Lefty Grove and George Earnshaw, and a fielding average of .975.

They also had Connie Mack, who was 68 that year and at the height of his power.

Perhaps Herbert Hoover should have been credited with an assist. The President threw out the first ball at the 1929 opener in Washington, saw the A's win the World Series finale that year and watched them perform twice in '30, once on Oct. 30 when the race was still close. The Athletics won all of the games Hoover attended.

Simmons, who nosed out New York's Lou Gehrig for the batting title by .381 to .379, provided the '30 opener with some high drama. He had rejected all of the A's offers and remained closeted with Mack, still dickering, when the other players went through their warm-ups. More than a few observers noted the absence and screamed in displeasure.

It was announced that the batting champ, unable to resist the fans' importunities, finally siezed a pen and scrawled his name on the contract. Some reports had him agreeing to a salary of $80,000 – Babe Ruth's rumored stipend with the Yankees.

At any rate, the bucket-footed slugger did sign, joined his teammates in batting practice amid a roar from the stands and, after a couple of swings in the cage, hit a home run off George Pipgras in his first official time at bat, helping the A's beat the Yankees.

Many expressed amazement that, apparently with no spring training, Simmons appeared to be in mid-season form. He was indeed in prime condition, he confided later, and for this he was beholden to the great Ty Cobb, who had wound up his career in 1928 with the A's.

Tris Speaker, the incomparable Boston-Cleveland outfielder, also ended his string with the A's in 1928 and perhaps only half-joking, Simmons used to complain that covering thev ground between the two oldsters knocked years off his career. With Simmons driving in 165 runs and Foxx 156, Grove (28-5) appearing in 50 games and Earnshaw (23-13) in 49, the Athletics clinched the 1930 American League pennant Sept. 18. The St. Louis Cardinals, winning 44 and losing only 13 in August and September, came on fast to nose out the Cubs by two games and become the National League champion. The Cards, under freshman manager Gabby Street, included George Fisher (.374), Gus Mancuso (.363), Frankie Frisch (.346), Charley Gelbert (.304), Jim Bottomley (.303) and Taylor Douthit (.301). The Athletics went into the World Series as favorites and, if he did not already know, President Hoover soon learned why. In the opener, Mack's men nicked Burleigh Grimes for only five hits, but all except one went for extra bases and, behind Grove, added up to a 5-2 victory on Oct. 1 at old Shibe Park.

Simmons tied the score with a homer in the fourth, and Max Bishop walked and raced all the way around on Jimmy Dykes' double in the sixth; Mule Haas tripled and crossed on Joe Boley's unexpected bunt in the seventh, and Mickey Cochrane homered over the right-field wall in the ninth.

A year or two later that wall was built higher, cutting off the view of hundreds who seated in makeshift wooden bleachers on the rooftops of the houses facing the park on Lehigh Avenue and Somerset Street. The enterprising residents, who charged for these accommodations, complained bitterly right up to the day that the stadium was razed, some 40 years later.

The lower barrier no doubt helped the A's offense in some slight degree, at least, and they continued their siege-gun tactics against the Cardinals. In the sixth and final game of the 1930 Series they followed their opening-game pattern almost exactly.

They got only seven hits of Bill Hallahan and his St. Louis successors Syl Johnson (later with the Phillies), Jim Lindsey and Herman Bell – but all seven were extra-base blows, which produced a 7-1 triumph.

The long ball proved the Athletics' shortest route to success. They chased Flint Rhem in the fourth inning of the second game, a 6-1 decision for Earnshaw as Dykes, Foxx and Haas contributed doubles and Cochrane homered.

The Cards benefitted from the familiar surroundings of Sportsman's Park in games three and four, winning, 5-0 and 3-1. Jesse Haines beat Lefty Grove with the help of two unearned runs in the fourth game.

St. Louis thus tied the series at two-all in games, but Foxx, the muscular Marylander, got the Athletics back on the track. With one out and Cochrane aboard via a walk, Foxx homered and the A's won in the ninth, 2-0.

So the A's were back in command, 3-2, in games, and returned to Philadelphia to wrap up the Series on Wednesday, Oct. 8. Although outhit, 38-35, the A's outscored the Cards, 21-12.

Shibe Park is gone now, and so are nearly all the men who played there. Connie Mack has been dead these many years, and his beloved Athletics are virtual tourists in the West.

But there has been at least one change for the better. One can say without fear of contradiction that the Phillies are a far, far better team than they were half a century ago.

Recall those thrilling days of 30 yesteryears

By Chuck Newman, Inquirer Staff Writer

The date was Oct. 1, 1950, the last time modern-day Pennant Fever hit Philadelphia.

It happened late on a Sunday afternoon at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn when Dick Sisler, a sprained wrist wrapped in adhesive tape, hit a three-run homer to launch the Phillies into what would be a disastrous World Series against the New York Yankees.

It had been 35 years since Philadelphia had a National League representative in the championship series, and even the A's fans in the two-team major league city toasted the champions after Connie Mack's team had beaten the Washington Senators, 5-3, at Shibe Park in the season finale.

It has been another long wait for Phillies fans, who have waited 30 years more for another shot at a championship. To some who were involved in the excitement of 1950s, the memory has faded a bit, but here are some recollections of those who are around for another try:

Temple athletic director Ernie Casale, then a 31-year-old mathematics teacher at Temple, a coach of the Owls' freshman baseball team and studying for his Ph.D. at Penn: "The nice thing I remember is that a member of that team, Granny Hamner, played with me in the service on a team at Aberdeen Proving Grounds. One night he came to dinner and brought Mike Goliat, who was about to play his first game, to the house. Everybody was quite excited, but I remember the disappointment when we lost all those one-run games to the Yankees."

Irv Kosloff, former owner of the 76ers, who was 36 then, and, as now, runs the Roosevelt Paper Company: "I went to all the World Series games. I was always a real sports fan. I think there was less sports awareness in the city then than there is now. I remember how badly I wanted the Phillies to win the World Series!"

James Tate, former mayor and in 1950 a 40-year-old real estate assessor for the city: "I remember the day they clinched the National League title. I remember listening to it on the radio in my backyard at 4029 N. 7th Street. I didn't have a TV in those days. We had heard the Phillies were going to come home by plane, and me and my 5-year-old son went into the backyard and waved our Phillies hats at the plane that went over that we thought the team was on."

Art Morrow, former Inquirer baseball writer, who was 40 and covered the A's on a regular basis but was assigned to the Phillies in the World Series: "I remember the team coming Into 30th Street Station after beating the Dodgers. They drove in cars to the Warwick Hotel for a celebration and there were people lined along the streets."

Leonard Tose, Eagles owner and then 35 and working for his father's company, The Tose Trucking Company: "I was at the game in Brooklyn when they won the pennant. I came back on the train with the team to Philadelphia. It was a wild ride."

Ray Kelly, former Bulletin sportswriter and then covering the A's: "There was no doubt about the excitement in the city. But there was also no question that it was a two-team city and had divided loyalties. I remember in those days all the players talked to the reporters. They were glad to. Everybody was making $12,000. Baseball was just beginning to get glamorous then."

Dave Zinkoff, 69 years old, former 76ers announcer and public address announcer at Shibe Park: "Oh, the Whiz Kids. They captured everybody's attention in 1948-49-50. When they beat the Dodgers, I hit the ceiling four or five times. I jumped higher than Wilt Chamberlain ever did. Everybody hoped they'd come out with a game or two and make it competitive."

Jack Steck, then a 53-year-old program director for WFIL-radio and WFIL-TV who is now, at 83, doing free-lance promotion work: "The story was the biggest thing in town then. Every station had to be involved. I remember the Bulletin had a display board with lights that flashed the scores. It was the center of attraction downtown. We used to send our reporters down there with cameras and tape recorders to interview the people watching the board. I think the atmosphere was better then, warmer. Now it seems that everybody's a critic. Some of the people at the ballpark who are screaming and booing now couldn't punch their way out of a paper bag. There were not so many boo-birds then.

Thacher Longstreth, president of the Chamber of Commerce, former mayorality candidate, and in 1950 a 29-year-old advertising space salesman for Life Magazine: "I was really an A's fan at that time because you must remember that when I was 10 years old in 1930, the A's were the world champs and the Phillies the world chumps. But it was a time when the city was beginning to notice the Phillies. I remember that in 1950 there was an air of enormous excitement, almost blind enthusiasm that has only been matched when the Flyers won the Stanley Cup. But there was also an air of indifference during the World Series, maybe a sense of fatalism, like it was a certainty that the Yankees would win."

Ruly Carperter, president of the Phillies, who was 10 years old when the team last participated in the World Series: "I was only about 10 then, but I can remember where I was. Of course Daddy (Bob Carpenter) was in Brooklyn when the team clinched the pennant, but I was at my grandmother's house listening to the game on the radio."

Paul Owens, vice president and director of player personnel of the team, who was 26 years old and a senior at St. Bonaventure University in Olean, N. Y. in 1950: "I was playing semi-pro baseball in Salamanca (N.Y.) at the time. A friend of mine had a lounge and we'd go early to get a seat to watch the games on television. I hardly drank at all in those days, except for a few beers, but the lounge was one of the few places you could watch the game. I didn't see the game where Sisler hit the home run, but I watched the World Series games."

At Yale, his Phils were ridiculed, but now he runs a Series team

Ruly Carpenter Interview with Allen Lewis

Eight years ago next month, Bob Carpenter stepped down as president of the Phillies after 29 years in the position and was succeeded by his eldest son, Ruly. Then the youngest club president in the major leagues at 32, Ruly Carpenter directed an operation that turned a last-place team into one that has won four National League Eastern Division titles in the last five years. Finally this season, the Phillies won their first pennant since 1950. In an interview with Inquirer baseball correspondent Allen Lewis, Carpenter talks about the Phillies past and present.

Question: When you were a youngster did you take a lot of heat from your friends over the failures of the Phillies?

Answer: Oh, yes. When I was in high school the A’s were still in Philadelphia, and in my particular class in school I think half the kids were Phillies fans and half were A’s fans. Of course, in the early ’50s we had a little bit more to cheer about, but when I went on to college we had some real bad clubs in Philadelphia, and we went through that horrible (23-game) losing streak, and I used to be ridiculed unmercifully by my teammates and classmates at Yale because we were lousy, there’s no question about it. Of course, by the time the ‘64 team evolved, I was out of college. I’m sure if I’d still been there when we blew it, I’d have caught hell when I went back that fall.

Q: Did that make you more determined to turn out a winner when you began running the club?

A: Well, in some ways it did. At one point, I considered going to law school when I was in college, and then I started thinking there’s no way we could really be this bad. If we hadn’t has that horrible losing streak back there in ‘61, I might have gone to law school. But I just sat back and said, “My God, there’s just no way that things could be this bad, and maybe I ought to look into this a little bit.” I made up my mind then I was going to give it a shot. When I went to work with the Phillies, I spent about a year, year and a half with (club treasurer) George Harrison to get a working knowledge of the economics, the money side of baseball, which, of course, today is all irrelevant to what happened then. Then I went to work with Paul (Owens) in the farm system and that’s really where my main interest lies today, that’s the only phase of this game I’ve ever totally enjoyed.

Q: When and how was the decision arrived at for you to succeed your father?

A: Daddy just made up his mind at the end of the ‘72 season, which was a horrible one except for (Steve) Carlton, that he was going to get out of it. I told him if he wanted to step down I’d be glad to accept the responsibility, but I tried to convince him that in spite of the ‘72 season in the next two or three years we were going to have a few things to cheer about, and I wanted him to be there, and if he wanted to retire then, at least he would have had something to be proud of. But he chose not to take that course and turned it all over to me and Paul. At times in the past he had said that some day we’d be running things, but I had no idea if it would be at the end of ‘72 or in November of 1980 for all I knew at the time.

Q: Why did you and Paul think Dallas Green was the man to manage the Phillies when Danny Ozark was removed late last season?

A: Well, that was kind of one of those deals where we have a tough mission, so we have any volunteers? And last year when we had to make a change with Danny, which was a very traumatic experience for all of us, Dallas more or less volunteered for duty and said, “Heck, I’ll run it for a month.” And it wasn’t like you were sending a guy down there who didn’t know what was going on or what he was doing. Dallas had managed at the minor-league level, which is not the major-league level, but still he had played, and he was intelligent enough to handle all the media problems and tough enough to take care of some of the field problems we had. Then, I was frankly very surprised when the season was over, and the club had won 18 and lost 11 in September, and Dallas walked in one day and said, “Guys, I kind of like this managing a little bit, and maybe I’ll give it a shot for 1980 if you don’t mind.” I said, “Dallas, I think you’re crazy, but if you want to do it, go ahead.” We had no reservations whatsoever about him doing it, it’s just why would a guy want to become a sacrificial lamb? So he went on down there this year and had done a fine job. He’s had a tough time in a few cases, but overall he’s been a plus. The young players and the veterans have all chipped in at various times. Dallas has had to crack the whip a little bit here and there, but it’s turned out to be a heckuva year for us.

Q: What was your reaction to the story when the club was in Montreal at the end of the season that Dallas wanted to give up the job if the Phillies won it all?

A: That didn’t surprise me at all. I think he just made an off-the-cuff statement. We hadn’t even talked about the manager situation for next year. For the last month, Paul and I have been so concerned with winning the division, and the managing situation for next year is just totally up in the air at this point. But it wouldn’t surprise me if Dallas doesn’t want to do it next year.

Q: Paul has talked about taking a less pressurized job one of these days. Is there any timetable along that line?

A: No, but I would imagine Paul feels the same way I do about all the other problems with the player contracts. I know it upsets him terribly to have to get involved in these things. It upsets me, and some times I feel like I’m going to go crazy. I would have to say Paul’s real interest still lies in the player development-scouting end of it. I’m sure when Paul retires as general manager he would enjoy advance scouting or, before the June draft, going around and looking at high school and college kids. I think that would make Paul very happy, because he totally enjoys the field end of this thing.

Q: There’s no secret about the fact that Dallas is the heir apparent whenever that happens, is there?

A: No, if Dallas chooses to become general manager of the Phillies, that’s fine with me. But times change and you never know.

Q: Were you happy with the progress of the farm system?

A: Yeah. You know you’re never 100 percent satisfied, but I hate to think of where the Phillies would have been this year without our farm system products.

Q: Are you concerned about the worsening relationship between your players and the media?

A: Yes. I’m concerned about it. I think it’s not just the Philadelphia Phillies, it seems to be prevalent today in professional sports, and I think it’s getting progressively worse in all sports. I think every writer down inside wants to have a good rapport with the players. I think they want the players to recognize them and talk to them. They might put up a façade, but I think they really want to be liked. On the other hand, they work for various newspapers, especially in a city like Philadelphia, where you’ve got four major dailies and they’re all in competition. And sportswriters are told by their superiors, “We’ve got to sell papers to stay in business, to compete with the other people, and we’ve got to have enough controversial items to get the job done.” So the writer is caught in a bind and when the guns are drawn they have to stick with their people, or they’re going to get fired or have to go elsewhere. It’s as simple as that. Of course, journalists say these players are professional and have to take the heat, but you can never understand until you have been the victim of one of these vicious articles. Most of these writers have never been the victims. They’re always the ones that dish it out. Even when they’re wrong on their facts. There was one article this year about our finance, and in it there were 18 inaccuracies. I talked to the writer and he apologizes, but nothing was ever done about it publicly. That’s just an example of what I’m talking about, and the same thing applies on these field situations. Then there was the drug thing that gave a lot of our players an excuse they were looking for not to talk period. The way the thing came out, our guys were all a bunch of junkies, and it really turned into a mess. That really did a lot to disintegrate the relationship between the press and the players. One big problem is that neither understands the other. I don’t think the players fully appreciate the sportswriter’s job. On the other hand, I don’t think some of the writers understand the players’ feelings. I think the only answer is an appreciation of each others’ jobs and closer communication, which is hard to do during the season.

Q: Win or lose in the World Series, do you foresee major changes in the ball club before next season.

A: I think this is the first year in a long time that we may have to make some, but everything is qualified by what you get in return, and you get into contractual problems…. But there are a couple of positions we’ve got to take a look at for the future. Now whether you can do it from within or from without, I don’t know. We’re not going to make some stupid deal out of emotion. And there are a lot of deals that you want to make that you can’t make because of contracts.

Q: How exciting was the win this year?

A: Next to 1976, which, of course, was the first one, this has been the most gratifying to me. In the other years, we had the lead, but this year we were written off and had to battle back. This was a great comeback.

Just seeing the Series will be something new for some of the Phils

By Lewis Freedman, Inquirer Staff Writer

During the 1975 World Series, when Pete Rose was a Cincinnati Red, he was asked what he would do if a visitor from heaven gave him a choice between making the Hall of Fame and being on a World Series champion.

“I’d plead with him- ‘Can’t I do both?‘” Rose answered. “If he came up from there, He’d understand.”

A few days later Rose, now 39 and the oldest Phillie, got his World Series ring when the Reds beat the Boston Red Sox. He also is certain for enshrinement in the Hall of Fame, but the comment illustrated just how precious the World Series is to Rose.

When he takes the field tonight against the Kansas City Royals, he will be starting his fifth World Series. But for the man who has accomplished more on a baseball diamond than any of his contemporaries, the World Series remains the ultimate.

Not many of his 25 teammates have shared the experience. Relief pitcher Tug McGraw made it to the World Series with the New York Mets in 1973, and pitcher Steve Carlton two, 1967 and 1968, with the St. Louis Cardinals.

That’s it.

The rest of the Phillies haven’t been there. They may be major league baseball players, but their memories of the World Series, its mystique, its special place in Americans’ hearts, have come from what they saw on TV as they were growing up.

Fourteen of the players weren’t even born the last time the Phillies were in the World Series in 1950, but they’ve been dreaming about what they’ve been missing.

“It will be the biggest thrill of my life,” said Ramon Aviles, who grew up in Puerto Rico and whose Series images revolve around Roberto Clemente in 1971, Pittsburgh versus Baltimore. “I always dreamed of signing a professional baseball contract, of playing in the major leagues, of playing in a championship series and then the World Series. All of my dreams have come true.

Aviles, like so many of the Phillies, hasn’t seen a World Series game that wasn’t brought to you by Gillette or Lite Beer. The first one he sees in person will be at Veterans Stadium tonight.

“I’ve watched it on TV every year,” the Phils’ backup shortstop said. “I don’t miss one.”

Larry Bowa, 34, the man ahead of Aviles in the lineup and a Phillie since 1970, looks like a little boy when he discusses the World Series. His eyes sparkle with the anticipation of Christmas morning.

“It’s probably the ultimate, every ballplayer’s dream. That’s what it’s all about,” Bowa said.

When he was growing up in Sacramento, Calif., Bowa became a New York Yankees fan, because they were always good and they were always in the Series.

“I always watched them (Series games), even if it meant staying home from school,” he said. “I used to watch the Yankees all the time. I loved the Yankees.”

He remembers the thrill of watching Don Larson’s perfect game in 1956, and he remembers almost matching that thrill when he attended a Series game for the first time.

“When the Mets won in New York in 1973,” Bowa said.

Broadcaster Tim McCarver, a temporary Phillie when he was activated in September to play in his fourth decade, played in the 1964, 1967 and 1968 World Series with the Cardinals.

“It’s the General Motors of your career,” said McCarver, who is on the sidelines this time. But for McCarver, the Series also kept him as busy as O’Hare Airport on Thanksgiving weekend.

The distractions of friends, family and strangers seeking tickets, the festive atmosphere, all made it “difficult at times to keep it all business,” McCarver recalled.

The fanfare and hoopla will be intense, McCarver said, and the best thing each Phillie can do is to be concerned about his performance.

“Concentrating is certainly the best way to be,” he said. “You’ve got a job to do. Concentrate on what you’re doing instead of the fanfare.”

Right until the leaves were falling from the trees, Marty Bystrom, 22, was concentrating on Clearwater in 1981, not Kansas City in autumn. The rookie pitcher spent most of the season in the minors, then went 5-0 in the majors, but he made the postseason roster only because of the shoulder problems of Nino Espinosa.

“I used to dream about pitching in it (the Series),” Bystrom said. “I could picture myself pitching in it and winning a ball game.”

Now that it’s real, he tones down the scenario a little. “I just want to get the chance to pitch in it.”

Bystrom grew up in Miami, and he hadn’t even seen a regular-season major league game until the Phillies brought him up.

Outfielder Lonnie Smith, 24, was born in Chicago, so his baseball upbringing wasn’t as limited as Bystrom’s. He knew exactly what playing in a World Series would mean to him.

“It means a ring on my finger and a good feeling, a joyful feeling inside,” Smith said. “It’s something every player dreams of.”

John Vukovich, 33, another Sacramento native, is another whose World Series view was shaped by what he saw on television growing up.

“I never went to a World Series game,” Vukovich said. “I’m from Northern California, so the Series that probably stands out in my mind is San Francisco in 1962 with (Willie) McCovey lining out to Bobby Richardson. And then there was Bill Mazeroski’s home run (to win it for the Pirates in the seventh game in 1960).

“Those were the two as a kid. But the best game, the most meaningful, was the sixth game in 1975. I was a Red early that year. I felt closer to it.” Now he will find out what he missed by being sent down to the International League.

These heroes and dramas of past World Series are what will reverberate in the minds of most of the Phillies as they stand on the baseline during the national anthem.

But there are older Phillies with different perspectives. Pitching coach Herm Starrette, 43, has two World Series rings from his days with the Baltimore Orioles, but he didn’t see how they were earned. While the Orioles were playing in 1969 and 1970, Starrette was analyzing the team’s young arms in the Florida Instructional League.

Starrette’s eyes sort of glazed over as he tried to picture himself on the field for Game 1.

“I’ll be like a 10-year-old kid,” Starrette said grinning like one. “Happy as hell.”

Who else but Rose to usher in a Series?

By Larry Eichel, Inquirer Staff Writer

On the eve of the National League playoffs, as the Phillies took batting practice, blissfully ignorant of the nightmares and thrills that awaited them, Larry Bowa started needling his buddy Pete Rose.

"We got you here," the Phillies' shortstop said, a half-joking reference to the fact that Rose had, in 1980, hit only.282, his lowest average in 16 seasons, that after 11 seasons with more than 200 hits he had been forced to settle for 185. "You take us the rest of the way."

That was what Pete Rose was brought to Philadelphia to do, to take the Phillies the rest of the way. Without him, the Phillies had won three straight divisional titles from 1976 through 1978 but had found nothing but humiliation and disappointment waiting for them in the playoffs. With him, team officials hoped and believed, the Phillies would become a team to be feared not just over the long season but in a short series, when the pressure was the greatest. Pete Rose would get them over the hump.

There was every reason to believe that Rose would help bring the team that intangible something that it seemed to lack in those frustrating years of one near-miss after another He was Charlie Hustle, perhaps the most respected and admired man in the game, a player who seemed to emanate confidence and effort. He could lead by word, and he could lead by example.

"Pete's what every player ought to be," his friend and former teammate Joe Morgan said the other day. "In Pete's mind, every game is like a World Series game. That's the way he treats it. That's the way he plays. I wish I could be like that. But I'm not. I wish everyone had Pete's attitude toward the game. But they don't. Basically, you've got only one Pete Rose. And it's a thrill just to be on the same field with him."

In his five playoff appearances with the Cincinnati Reds, Rose had sparkled under the spotlight; he had thrived under the pressure. He had compiled a.378 lifetime playoff average, going 9-for-20 against the Pirates in 1972 and 6-for-14 against the Phils in 1976. His Cincinnati teams had won four of the five scries in which he had appeared.

So the Phillies purchased Rose's services on the free-agent market for over $3 million, buying his 3,000 hits and his 44-game hitting streak and the promise of his assaults on dozens of career hitting records. In the bargain, they figured, they had bought a World Series for Philadelphia.

Pete Rose understood that very well at the time. And he understands it now.

On Sunday night, in the winning locker room at the Astrodome, he sat calmly amidst the noise and the chaos of the wild celebration around him. He drank his champagne, looked around and smiled. He had the air of a man who had seen it all before, but was enjoying it just the same.

"This is what they got me for," he said. Right?"

Rose did not win the pennant alone. Manny Trillo, chosen the most valuable player of the absurdly dramatic championship series, performed splendidly in the field and at the plate. Greg Luzinski, Garry Maddox and Del Unser all contributed hits that loom immensely important in retrospect.

But Rose was a joy from start to finish. He hit.400 for the series, getting eight hits in 20 official at-bats. In addition, he drew five walks, giving him an on-base percentage of.560.

"I started swinging the bat the last week of the season," he said, "and I'm just happy I could carry on right through the playoffs. And we're going to the World Series."

In the playoffs, Pete Rose was the leader. In the eighth inning of Game 4, with the Phils trailing, 2-0, and six outs away from elimination, he bounced a single past the diving Morgan. It wasn't much of a hit, but it brought home a run, which the Phillies hadn't been able to do for the previous 18 innings. From that point on, Houston pitching would no longer hold the seemingly unfathomable mysteries it had held for the Phillies.

But the one image that will remain in the memory long after most of the highlights and lowlights that cluttered this playoff is forgotten comes from the 10th inning of that fourth game. It is the image of Rose, representing what would turn out to be the winning run, charging around third on Greg Luzinski's double to left. As he heads for home, it is written on his face that he will score the run – even though the throw may beat him home – and that the catcher who must block the plate docs so very much at his own risk, as Ray Fosse learned in the 1970 All-Star Game.

"Sure it was a gamble," he said. "But it paid off."

His role in Game 5 was less dramatic; He got one hit, though it proved to be meaningless. He did battle Nolan Ryan for a walk that forced home a run in the five-run eighth, and he had to foul off a tough 3-2 pitch to get it.

But Rose helped win the deciding game in a way that would have been unusual for him in years past. He won it with his glove. In his career, Rose has been adequate defensively – sometimes more, sometimes less – as a second baseman, third baseman, leftfielder and right-fielder. Only at his current position, first base, has he achieved the status of craftsman – at the age of 39.

On two successive plays in the fifth inning, he saved a run for the Phillies, a run which could have sent the Kansas City Royals to the Astrodome for the World Series instead of to Veterans Stadium.

First, he lunged to his right to snare Morgan's smash and rob his former teammate of a hit. Then, with Enos Cabell on second, Jose Cruz hit a grounder to Trillo. Manny's throw to first pulled Rose off the bag as Cabell rounded third and headed for home. Rose promptly gunned down Cabell at the plate.

Rose, who is a man given neither to braggadocio or to false modesty, thought those plays rather significant.

"I was very happy with the way I played defense in the series," he said. "I thought I saved a lot of runs. When you're not knocking in runs, You've got to save some runs."

And he was very happy that he could deliver on the implied promise of his four-year contract with the Phillies, that he help bring a World Series to Philadelphia, that he somehow rip the monkey off this team's back.

"I'm very happy for the fans in Philadelphia, more so than I am for myself," he said, "because of the way they support their ballclub. I know this team has been close so many times, and the fans really deserved a winner. I know they must have died when we were down in the fifth game, 2, and that we go ahead, 7-5, and they come back and tie it – the fans must have been tearing down the Liberty Bell or something... I was having a lot of fun out there.”

One of the great attractions of Pete Rose is that he, unlike many players, is a great fan of the game, a walking treasure trove of baseball history and trivia. He can tell you that his 3,557 hits place him third on the all-time National League list, only 73 behind leader Stan Musial, or that he's first in singles, second in doubles and second in runs scored.

So when he offered the judgment that these playoffs with Houston were something special, that judgment had some substance behind it.

"This sure was the most exciting series," he said. "The ‘72 playoffs (a five-game series between Cincinnati and Pittsburgh won by the Reds in the last of the ninth in the fifth game) had a couple blow-outs in them, and the ‘73 playoffs (the Reds and the Mets) were pretty strange because of the way the people behaved in New York. But this one was so emotional up and down. And there were so many emotional highs and lows, which is really tough on you. No one quit. They just kept coming back. It was the type of series where it looked like whoever batted last was going to win."

As he sat at his locker, sipping his champagne, someone asked whether the champagne always tastes the same, whether the bottles are uncorked in honor of a division title, a pennant or victory in the World Series.

"No, the World Series champagne is the best," he said. "That makes you number one. We're just tied with Kansas City right now. All you can do is play hard. You got to beat a tough team, Kansas City, that beat the Yankees three games in a row. It ought to be a great show for baseball."

Indeed, it ought to be a great show, if only because it will give the people of the United States the opportunity to renew their acquaintance with a familiar figure of Octobers past, one Peter Edward Rose.

A trip through hell, but Phillies arrive laughing in heaven

By Frank Dolson, Inquirer Sports Editor

It was the perfect ending for a baseball team that did everything the hard way... a perfect finish to a 30-year struggle by the Phillies to bring a World Series to Philadelphia.

If the 10-inning, 5-3 victory that kept the Phillies alive in Game 4 of the National League Championship Series was an emotionally draining experience, if the 10-inning, 8-7 victory in Game 5 that earned this team the pennant – and the recognition – that had eluded it so long was even tougher, then it was in keeping with an entire season of ups and downs, giddy highs and sickening lows.

Somewhere, at some time, there may have been a professional sports team that went through more than the 1980 Phillies.

Somewhere, at some time, there may have been a team that had more to prove to even its most ardent supporters than the 1980 Phillies.

But I don't know where.

This was supposed to be a club of "fat cats", a group of high-paid, under-motivated baseball players who had all the talent in the world, but not enough desire, not enough heart to win when the going got tough.

It wasn't until just before midnight on Sunday, when Garry Maddox clutched Enos Cabell's fly ball for the final out, that the sports fans of Philadelphia, the sportswriters of Philadelphia, that everybody in Philadelphia really believed that this club could do it.

The doubts were apparent, even as the club drove through the stretch in pursuit of the Montreal Expos. The fans had to be convinced that the 1980 Phillies were for real, that they cared, that they were willing to do whatever was necessary to bring a World Series to the Vet.

The reason was clear. Past Phillies teams had disappointed their fans too many times, failing to win a single home game while losing three consecutive National League championship series.

But in the end, the team that did everything the hard way from day one, won the big series – the big game – in the hardest way imaginable.

Manny Trillo played second base brilliantly all season and was spectacular in the five-game showdown with the Astros, making superb plays, delivering clutch hits and earning the award as the most valuable player.

Bob Boone, so loudly booed through most of the season, delivered a vital, two-out, ninth-inning hit that kept the Phillies alive in the division clincher in Montreal, then came through with a two-out, two-run hit off one of Nolan Ryan's fastest fast balls in the pennant-clincher.

Garry Maddox, the center of a controversy late in the stretch drive, came through with two gigantic clutch hits – a two-out single in the 15th inning that saved the Phillies from what would have been a costly, perhaps fatal, defeat to the Cubs on the final Monday of the regular season, and the pennant-winning hit, a two-out line drive to center that fell just in front of a desperately charging Terry Puhl in the 10th inning Sunday night.

Larry Bowa, a frequent target of the boo-birds and for a time mired in the first fielding slump of his career, turned what had been his unhappiest season as a Phillie into his happiest by playing shortstop the way he had played it for a decade and chipping in with several important hits, including the one that triggered Sunday night's five-run eighth.

Greg Luzinski, who struggled and suffered through much of 1980, came through when it mattered most, getting the game-winning hits in Games 1 and 4.

It didn't matter that Mike Schmidt, who had led this team throughout the season with his home run and RBI production, hit only.208, with no homers and one RBI in the playoffs. His teammates picked him up – and that is the mark of a truly fine ball club.

It didn't matter that Pete Rose turned 39 early in the season. He played with the verve, the daring, the aggressiveness that has always been a Pete Rose trademark.

In the playoffs Rose hit.400. He made a mad, stop-me-if-you-can dash from first to home on Luzinski's two-out, 10th-inning double to win Game 4. He worked Nolan Ryan for the bases-loaded walk that pushed across the first run in the big eighth inning in Game 5. And he made so many outstanding plays at first base you'd have sworn he had been playing there all his life.

Game after game in the playoffs, there was Rose, standing in front of the dugout, urging his teammates to get the big hit, to start the big rally. If anybody ever had the slightest doubts that signing Rose as a free agent was a good move for the Phillies, his performance under pressure in the last couple of weeks surely dispelled them once and for all.

But above all, this was a team victory by a ball club that spent what seemed like an inordinate amount of time trying to become a team.

Ironies abounded. In the spring, this was supposed to be a club without pitching. As September turned into October, it was pitching that kept the 1980 Phillies alive. Not just Steve Carlton, who zeroed in on his third Cy Young Award, but Dick Ruthven and Larry Christenson and a kid named Marty Bystrom... and an irrepressible older fella named Tug McGraw.

This was a team that seemed, at times, to be at war with its manager. And yet, when Sunday night's drama had run its course, there were some of Dallas Green's severest critics embracing the man.

"I think," said Greg Luzinksi in the glow of this team's greatest victory in three decades, if not of all time, "we proved to the world that we don't have a quitter on this team."

"The bench never let us get down, even when they (the Astros) went up by three," Larry Bowa said. "The guys never stopped talking and clapping.... I never have been associated with a team that had more character."

So there it is – the incredible saga of a baseball team that went through hell for the better part of six months – and wound up in heaven.

And took a lot of nonbelievers along for the ride.

Series TV: Garagiola’s big fall hit

By Lee Winfrey, Inquirer TV Columnist

Among the many former baseball players who now cover the game on television, probably the best-known is Joe Garagiola. He will be the main man at the microphone when the World Series begins tonight at 8 on NBC (Channel 3).

Garagiola’s long-time partner in the booth, Tony Kubek, will be with him again, along with Cincinnati pitcher Tom Seaver, working as a color analyst. An added starter will be former umpire Ron Luciano.

The standard pattern is for Garagiola to handle the play-by-play for the first four innings and the last three, with Kubek the lead voice during the fifth and sixth innings. Garagiola also has charge of any extra innings.

Luciano will be available to comment on any controversial umpiring decisions. NBC, hamming things up a bit, also plans to dress up Luciano like Darth Vader tomorrow night for a pregame spoof entitled, “The Umpire Strikes Back.”

Garagiola and Telly Savalas are probably the best-known bald-headed men on TV.

Garagiola said he wore a wig home once, but “my family laughed and the dog ran under the bed.” So now his pate gleams like a sun field every summer.

It hasn’t hurt his longevity. Savalas’ “Kojak” series was cancelled some time ago, while Garagiola is rounding off his second decade of TV work for NBC.

As everyone knows, he didn’t get the job because of his prowess as a player. Garagiola batted an unassuming .257 during nine years as a catcher with four major league teams in the 1940s and 1950s.

Garagiola, 54, was best-known as a catcher for the St. Louis Cardinals. He collected his only World Series ring for his work with them, batting a respectable .316 in the 1946 Series, in which the Cards beat the Boston Red Sox.

Garagiola grew up in St. Louis, in an Italian neighborhood called The Hill. “My father was a laborer,” Garagiola said. “He made clay pipe in a brickyard in St. Louis. He never learned to speak English.”

Garagiola’s English is a warm-hearted, affectionate commentary on a game he loves. He will point out mistakes on the diamond, but he clearly cares about the boys of summer and seems sympathetic to them all. He never carps or sneers or belittles.

Asked how the announcers will divide up their chores, Garagiola said he and Kubek would work much as they did through the summer on NBC’s regular Saturday-afternoon telecasts.

“Seaver’s contribution is to sort of update us,” Garagiola said. “As much as Tony and I hang around ball parks and players, it’s not like pitching against them.

“Seaver will concentrate on the pitching aspect,” Garagiola continued. “He’ll have a man next to him charting the pitches, what they are. I assume he’ll have one of those radar guns (to time the speed of pitches).”

Seaver won 10 games and lost eight for the Reds this year. He is no rookie in Series announcing, since he also worked with Garagiola and Kubek two years ago.

Although NBC’s camera work on the Series is always glossy and often stunning, Garagiola said he tries to keep things relatively simple in the announcing booth.

“Our philosophy is to follow the ball,” he said. “If you got a lousy game, you got a lousy telecast. The important thing is still the big five: the score, who’s batting, the count on the hitter, the number of outs, and the inning they’re playing.”

For NBC, Garagiola concentrates almost exclusively on baseball. “I’ve never wanted to go into football or basketball,” he said. “Baseball I see as both a former ballplayer and a fan.”

As for the Series, Garagiola said he wants only one thing. “I just hope,” he said, “that everybody comes in and plays the way they did that got them there, that nobody makes a big mistake that becomes well-known because everything is so magnified. You mention Mickey Owens’ name and everybody thinks of a third strike.” (Owens, a catcher for the old Brooklyn Dodgers, dropped a third strike that lost a key game in the 1941 World Series to the New York Yankees).

Meanwhile, back in the counting room, the bookkeepers at NBC know what they want. They don’t care who wins, but they would like a Series that lasts at least five games.

The major leagues charge the networks such a high price to telecast the Series (NBC in even-numbered years, ABC in odd-numbered years) that a network loses money on a Series that lasts only four games. The break-even point is the fifth game. With Series commercials priced at $125,000 per 30-second spot this time, six or seven games would bring their usual big profit.

The man in charge of making it all look beautiful is, as usual, Harry Coyle. For the 32d year, he will direct the Series coverage.

Coyle, 58, broke in at the very beginning, when the Series was first telecast in 1947. “Bill Slater, Bob Stanton, and Bob Edge were the announcers,” he recalled in an interview. “We had only four cameras. In comparison to today, it was a Model-T Ford compared to a new Mercedes-Benz.”

The number of cameras has tripled since then. But as Coyle moved on through the years, passing such landmarks as 1955, the year the Series was first telecast in color, he was able to handle all the improvements because they proceeded by degrees.

Coyle won an Emmy Award for his most recent Series stint, in 1978. A crowd-pleasing addition he came up with then was “four-point isolation coverage.” With it, a piece of action can be replayed from four different angles.

“We don’t set up replays just because we want to look like big shots,” Coyle said. “But if a man slides into third and the third baseman drops the ball, there may be only one angle where you’re able to exactly see the ball go into his glove and drop out. That’s the one we’re aiming for, to show you what really happened. Of course, if you get a sensational play, we’re gonna hit you with all four (replay angles).”

For the Series, Coyle will be in command of 10 stationary cameras, called “hard cameras,’ and two roving hand-held Minicams, called “creepies.”

“The creepies float around the stadium giving us unusual shots,” said Coyle. “One might get up on the scoreboard, or go into the stands to shoot players’ wives, or even sneak around the dugout. They (the creepie cameramen) are tired at the end of the show.”

The 10 cameras in fixed positions will cover the game action. You’ll probably find, Coyle indicated, that NBC’s coverage of the live action will look much like ABC’s did during last week’s National and American League playoffs.

“You’ll find the difference in replays,” Coyle said. “We feel our replays are more effective. I’m not talking about the number of replays. I’m talking about the type.

“We don’t use the program replay, replaying what you just was, which ABC does quite a bit. When NBC runs a replay, it’s off a different camera.” Hence, Coyle contends, more variety in NBC replays

Coyle’s cameramen, who average 15 to 20 years of Series experience, never have to guess what they should shoot. Who should do what is all spelled out beforehand in an 11-page “shot sheet,” sometimes called “the Bible,” which covers every cranny of the field.

Most of the shots you will see come from camera 7, high in center field, which shows the pitcher delivering the ball down the alley to the batter. The assignment considered the toughest, however, is camera 2, high behind home-plate, which must follow the ball when it is hit. During the Series, Al Rice will be operating camera 7 and Mario Ciarlo will be on camera 2.

Only five of the 10 cameras are equipped to tape replays, however, and cameras 7 and 2 are not among them. So NBC won’t give you any rehash of what you’ve already seen on them.

The Vet was built for a time like this

No Author Listed

This is the Phillies’ third World Series, and Veterans’ Stadium is the third stadium in which the Phillies have played those Series.

The first time, against the Red Sox in 1915, they were in the Baker Bowl, the 15,000-seat park at Broad and Huntingdon Streets that was the grandest in all of baseball when it was built in 1887. By 1950, when they played the Yankees, they were sub-letting from the A’s at Shibe Park, another of baseball’s landmark edifices.

Now, in 1980, it’s the Vet, and while the Vet may not be decades ahead of its contemporaries in the National League, it is a model of a modern, multiple-use stadium that is especially good for baseball.

The Vet is not any sort of trend-setter, however. It is cut from somewhat the same mold as the modern stadiums that have become standard through much of the National League- Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Houston, Atlanta, St. Louis- and like all of those, it was built to accommodate both baseball and football.

The Vet, however, is a bit more like a real ballpark than the others, and the reason is that, unlike the others, it isn’t really round. The Vet is more like a rounded square, rounded both on the sides and at the corners. It’s a subtle difference, but it’s what makes the Vet, even though it has other uses, a baseball stadium rather than a stadium that’s used for baseball.

Thanks to the rounded-square shape, as opposed to the circles in Pittsburgh and the others, the fans on the sides, especially those in the upper deck, aren’t as distant from the action as they would be otherwise. And the fact that the stadium does have corners, rather than being a continuous circle, makes the field closer to the traditional ballpark shape, creating more room in straightaway center field.

The dimensions at the Vet are 330 feel down the lines and 408 to center.

The field differences are subtle ones, however. At the gate, the difference can be expressed in raw figures.

When the Vet was opened on April 10, 1971, the capacity for baseball was 56,581. Through various alterations, it has since been raised to 64,976, highest in the National League and second in major league baseball only to Cleveland’s antiquated lakefront giant.

In its 10 seasons, the Vet has yet to develop much in the way of famous “this-is-the-spot-where” memories (although there is one spot of left-field wall that Greg Luzinski’s glove hand would prefer to forget). But that may have less to do with the Vet itself than with the somewhat antiseptic turn that baseball has taken. In fact, the Vet may be one place where part of that antiseptic trend is being battled. Although the Dodgers play to worshipping millions in Los Angeles, Phillies fans are probably the closest thing in baseball today to the half-crazed, ever-despairing fans of Brooklyn 30 and 40 years ago.

What it all adds up to is that in 1980, when baseball is changing but some of the atmosphere of by-gone games is still welcome, the Vet is an ideal World Series ballpark. And what’s more, it’s in Philadelphia.

Royals offer a stadium for the baseball purists

In these days of multiple-purpose stadiums, when a single tenant usually isn’t enough to pay the municipal rent, Royals Stadium is a bit of a throwback, but in an “everything’s-up-to-date-in-Kansas-City” style.

Royals Stadium is a ballpark, pure and simple. It was designed strictly for baseball and has been used strictly for baseball. Even such classic old-time ballparks as Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and Fenway Park in Boston have allowed a football team to trespass at one time or another. But Royals Stadium, like its Dodgers counterpart in Los Angeles, is for baseball.

Royals Stadium is Kansas City’s second major league ballpark. The first, Municipal Stadium, housed the A’s, after their move from Philadelphia in 1954, and the Royals, in the early years of Ewing Kauffman’s franchise.

That rickety structure, however, was not bound to suffice for long, and the changeover came on April 10, 1973, when Royals Stadium was opened as part of the Harry S. Truman Sports Complex.

In its first year, most of the notice that Royals Stadium received had to do with its water show, a 322-foot wide collection of fountains and waterfalls, just beyond the right field wall.

Since then, however, as the Royals have attracted more and more attention on the field, the water show has attracted less and less.

Still, the park itself is a very attractive one, not an easy piece of architecture for its occupants to upstage. The most striking feature is the crescent-shaped upper deck, dozens of rows deep behind the plate but narrowing down to points as it nears the foul poles.

When it was opened, Royals Stadium was described by United Press International as “perhaps the finest facility for the game ever erected.” Fans of the Chicago Cubs and others might argue with that, but there is no question that Royals Stadium is an ideal place to watch baseball. Despite its modern magnificence, it is one of the smaller parks in the major leagues, with a capacity of 40,672, and it doesn’t leave too many fans feeling distant from the action.

Get set for a show from Willie Wilson, the flying Royal

By George Shirk

When Willie Wilson reaches first base, and he does a lot, fans in Kansas City’s Royals Stadium sit up and start to buzz. When Wilson takes his lead, the buzz gets louder. And with each pitch that Wilson chooses not to steal, the tension mounts until, spotting his chance, he glides like a jet to second and logs yet another stolen base.

Then the noise really begins. It rolls out of the stadium, masking all other noise about. It rolls out over the stadium waterfall, over the freeway, down towards Independence and back toward downtown Kansas City. Willie Wilson turns the Midwest on.

Willie Wilson is one of the fastest, most exciting men in baseball, and tonight he is making a rare appearance in a National League city with the American League champion Kansas City Royals. It’s the World Series, a perfect showcase for this 25-year-old outfielder from Summit, N.J.

Were it not for George Brett, Wilson clearly would be the star of this Kansas City team. “He’s the most exciting player in the game today,” said Royals vice president John Shuerholz.

“I think, once he starts stealing bases on a combination of speed and technique, that he could steal 125 bases a year easy,” said Royals manager Jim Frey. “Right now he’s stealing on speed.”

Here’s what Willie Wilson has done:

He led the American League in stolen bases last year with 83 and was second this year with 79. His two-year total of 162 is the highest since 1915-1916 when Ty Cobb stole 154.

This year, he set a league record by stealing 32 consecutive bases. He stole third base eight times. His five inside-the-park home runs last season is believed to be unequaled in major league history.

Said New York Yankees catcher Rick Cerone: “He really doesn’t steal bases. Most of the time he just outruns the ball.

“But,” Cerone added, “you can’t steal first base.”

But with the kind of year Wilson had in 1980, he might as well have just taken first as a gift. He was standing on it much of the time.

His combination of hitting average and base-path speed gives Kansas City a leadoff threat that was largely responsible for the Royals’ walkaway from the rest of the Western Division this year.

He was seventh in batting average this year in the AL, hitting .326. His total at-bats (705) was a major-league record. He led the league in runs scored (133) and rang up a league-leading 203 hits (sic).

He set a league record for most hits by a switch-hitter with 230 (George Weaver of the 120 White Sox hit safely 210 times) and that tied a major league record set by Pete Rose of the 1973 Reds.

He became only the second player in major league history in major league history to get at least 100 hits from both right side and left side of the plate, joining Garry Templeton of the Cardinals, who did it in 1979.

In short, Wilson is one of the most dangerous threats to the Phillies and he promises to be one of the most exciting players to watch in the 1980 World Series.

When Wilson gets on first base and decides to steal, he succeeds 85 percent of the time.

Despite that success, during one three-week stretch this season he decided not to steal. He said he wanted to prove that he was more of a ballplayer than a baserunner, that he was a hitter of skill and a fielder, too.

.

Wilson never counted on playing baseball until the Royals pull what was considered a major coup by convincing him to abandon a University of Maryland football scholarship. Other teams had tried and failed. The lure of a reported $90,000 bonus didn’t hurt Kansas City’s chances in the 1974 June draft. “Football,” Wilson said, “was the sport in the town I came from.”

Wilson grew up in a household that included himself, a brother, his mother and his grandmother.

“It wasn’t a ghetto situation or anything like that,” he said. “But we could use the money then.”

.

“On the day of the draft,” Schuerholz said recently, “a number of scouts, general managers and directors of minor league operations came by our table to say that we’d never sign him- that he’d play football.

“Some of them even told us that they’d talked to Willie a day or so before the draft and that he’s sworn that he was going to play football.

“There’s a lot of excused around the league these days on the Wilson signing,” Schuerholz said, “but the fact of the matter is that we did our homework better than they did.”

Wilson didn’t become a hitter until he learned to switch-hit in the minors. His best average as a right-handed hitter was .272 at Waterloo and he had never hit above .281 until he hit the major leagues last year.

“He’s going to get better,” said Jim Frey. “He’s learning to hit now, and he hasn’t developed like some of the older guys we have. He’s not yet as disciplined. That’s one of the things he’s got to do, get a feel for hitting, to go for the big numbers.