Philadelphia Inquirer - October 21, 1980

A city, a team gear for a long-awaited celebration

By Frank Dolson, Inquirer Sports Editor

In 1915, the Phillies clinched their first National League pennant, in Boston.

In 1950, the Phillies clinched their second National League pennant, in Brooklyn.

In 1976, the Phillies clinched their first National League East division title, in Montreal.

In 1977, the Phillies clinched their second National League East division title, in Chicago.

In 1978, the Phillies clinched their third National League East division title, in Pittsburgh.

A little more than two weeks ago, the Phillies clinched their fourth National League East division title, in Montreal.

A little more than one week ago, the Phillies clinched their third National League pennant, in Houston.

Never have the Philadelphia Phillies won anything – a division title, a pennant, anything –– in front of the home fans. And now tonight, the team that has never won a title-clinching game of any kind in its home park in the 20th century, the team that has never won a world championship in any park in any century, has an opportunity to hit the jackpot at Veterans Stadium.

This could be... should be... the kind of night dreams are made of, a night that will be remembered as long as sports are played in our town.

If the Phillies beat the Kansas City Royals in Game 6 – or, failing in that, Game 7 – of the 1980 World Series, it should be an unforgettable night, a beautiful night for a city that takes its fun and games more seriously than most.

But it could also be a night in which a tremendous sports achievement is used as an excuse to destroy property, to injure people, to tarnish the image of the city, to turn a beautiful night into an ugly one.

It's sad that at a time like this, with the Phillies one victory away from a world championship and the inhabitants of the fourth largest city in the nation hanging onto every pitch, there has to be a dark cloud hanging overhead – the possibility of some "fans" getting carried away and ruining the night for all those who simply want to enjoy it. But this is 1980… and the threat is most surely there.

Remember the last game at Connie Mack Stadium, a decade ago, when an historic night turned into a frightening one, when people literally ripped the old place apart; injuring dozens in the process?

Ruly Carpenter remembers. He knows, as we all do, that only a very small percentage of the fans are responsible for destroying what should be happy occasions. But he also knows that “you always get that 1 or 2 percent – and you know mob psychology, when a couple of them run out there then everybody wants to.... Hell," he said yesterday as the Phillies held their final off-day work out of the season, "when they tore old Connie Mack Stadium up I saw guys with three piece suits carrying toilets out of the men's room. I mean they were well-dressed people, and they started tearing things up like the rest of them."

That memory... and the memory of all those people with the bashed-in, bleeding heads who were carted into the first-aid room that night... and visions of other scary incidents here and elsewhere in the last decade or so are enough to temper the joy this city feels today as Steve Carlton prepares to pitch the sixth game of the World Series.

"That's why I wanted to win (clinch the Series) at Kansas City," Phillies' owner Carpenter said. "I never went to sleep last night (following the fifth-game victory)."

He wasn't sitting up worrying about how Carlton would do against the Royals. He was thinking about what might happen if the Phillies win and all hell breaks loose at the Vet.

And Ruly Carpenter wasn't the only person with such thoughts, on his mind.

"Sounds like a riot to me," Dick Ruthven said about the possibility – no, the probability – of the Phillies wrapping up this World Series at home. "Sounds like insanity. I'm wondering how we'd get out of the ballpark to go home."

"I thought about it coming home (from Kansas City)," Larry Bowa said. "We got here and people were going crazy – and it was approximately 1 o'clock in the morning."

There was a crowd at the airport when the team arrived after its dramatic last-inning win in Game 5, and there was a crowd at the ball park, where the players went by bus to pick up their luggage.

"People were yelling, 'You ain't seen nothin yet.'" Bowa said. "There must have been about 300 people here (at the Vet). We couldn't even get in the door to get our stuff."

Such enthusiasm is great, if it doesn't run wild, a possibility that has occurred to just about everybody connected with the ballclub.

"It's something you think about," Bowa said. "It's also something you're sort of scared of. I've seen it happen when Chris Chambliss hit that home run (to win the 1976 American League playoffs for the Yankees in New York). I know the people are going to be excited if we win. I know it's something that might not ever happen again. But you've got to be careful or there are going to be people getting hurt."

And some of those people getting hurt could be wearing baseball uniforms.

Beating the Royals tonight figures to be tough. Getting off the field after the final out in the event the Phillies do beat the Royals figures to be even tougher.

"Yeah, I'm concerned about it," Bowa said. "I'm really concerned about it. Especially if it ends with a pop fly. They're liable not to let the thing come down.

"I just hope if we are fortunate enough to win, it's a three or four-run game. It's hard to put your attention on getting off the field when you're in a close ball game."

But, as Bowa was quick to point out, this Phillies club seems to play only close ball games these days.

One thing is certain: The security personnel at the Vet and the city police are preparing for this potential night of nights with their eyes wide open.

"They've had a master plan for the last four, five years," Ruly Carpenter said, "but they've just never had to use it."

Now, thanks to all those storybook rallies, they're on the verge of having to use it.

"The key to the thing," said Carpenter, "is keeping people from the 5-6-700 levels from getting down to this (field) level. You've got to keep them from filtering down during the game. What they try to do, they'll sneak down in twos and threes, and if your security guards aren't on their toes by the eighth or ninth inning you've got 400 or 500 of them."

That's what happened the day the Mets polished off the Cincinnati Reds in the final game of the '73 National League playoffs. By the time the last out was made, the mob was in position to swarm onto the field, overrunning box-seat patrons along the way. Anybody who was there that afternoon will never forget the sight of Cincinnati plavers armed with bats to protect Pete Rose as he dashed through the crowd to safety. It was scary.

That's what can happen in today's world... and that's why the Carpenters, the Bowas, everybody is approaching tonight's game with a mixture of fear and joy.

Surely, no one is more aware of the explosive possibilities of the situation than Pat Cassidy, the Vet Stadium's director of operations. Late yesterday afternoon, as the Phillies concluded their workout, he was sitting in his office, trying – as he had been for more than an hour – to eat the plate of pork chops and vegetables that the Eagles had sent down to him. The phone had never stopped ringing. Except for one bite, the pork chop, now in an almost petrified state, was untouched.

Life won't return to normal for Pat Cassidy until this World Series is history.

"I beefed up my security by, I guess, one-third," he was saying, and then he talked about all the extra police assigned by the city. "They're going to be all over the place," Cassidy said. "We're going to have cops on horses. They'll come out in the seventh inning probably to show the people they're there. We're just hoping everybody behaves. This (the championship the Phillies are on the verge of winning) is something the city, the whole Delaware Valley should be proud of. We're not going to let 'em tear it down, destroy it.

"We're going to try to appeal to the fans. They're the ones – the people in the stands – who've got to realize they can destroy our image. If we throw a couple of guys off the field (for running out during the game), don't make heroes out of them. Those heroes are going to go to jail."

The place for the fans tonight is in the stands, not on the field. This is a night that should be enjoyed to the fullest, a night for every sports fan in this city to cherish. It could be – should be – the most beautiful night in many years... if nobody destroys it.

From bleachers to stardom, Daisie White’s son stays at home

By Steve Twomey, Inquirer Staff Writer

KANSAS CITY, Mo. – The cops were always cool. No hassles. They knew the kids from the neighborhood couldn't afford Municipal Stadium because the neighborhood around 22d Street and Brooklyn Avenue was hardly high-rent. It was, and still is, the inner city, not bad perhaps by East Coast standards but bad nonetheless.

So the cops always winked when the kids from the neighborhood scaled the football bleachers at Lincoln High School, right beside Municipal Stadium. From there, from the very top rows, they could peer Inside the old place, over the left-field foul line, and see their dreams brought to life: major league baseball, the Kansas City A's, Ed Charles and John Wyatt and the rest of the teams from the early '60s.

"You'd have to arrive about an hour before the game," one of those youngsters, Frank White, would recall years later. "For a big series with the Yankees, I think the largest crowd (on the football bleachers) might have been a hundred or so. The best view was from the far north corner. We'd sit and listen to the old-timers talk about the players and the strategy and the games. We learned a lot about baseball from listening to those old guys."

And after the games, White, now one of the best second basemen in the country, a $150,000-a-year fielding wonder for the Kansas City Royals, would walk the 10 blocks home, past the modest single-family homes to the one at 2904 Olive Street, a two-story, stone-and-wood house his family had owned since moving in 1960 from Greenville, Miss. He'd tell his mother what he had seen. He lived baseball, breathed it, and she'd watch his eyes grow big.

"He used to say, 'Mamma, I want to play in that stadium some day,'" his mother said yesterday from a chair in the living room of that same old house on Olive.

He never got his wish. Municipal Stadium, like Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia, is no more. Lincoln High School is still there, perched in red brick on a hill, but now those football bleachers overlook, emptiness, two blocks of rolling grass surrounded by a chain link fence.

What he got, though, was better. Life turned out more glamorous than his schoolboy imaginings.

Because now, all the baseball world knows Frank White. On his own, he had snuffed out rally after rally by the Philadelphia Phillies in the 1980 World Series.

Ground ball up the middle, a sure base hit. White darts to his right, backhands, and somehow a runner is out at second base. Now, his back is to the infield, and he is scurrying madly into right field. Somehow, a fly ball lands in his glove. And now, he dances to his left and knocks down another would be hit. It is ballet. Ask Manny Trillo. Ask Larry Bowa.

It is a storybook story, the local kid who turns into a Worjd Series hero for the home team, the only member of the Kansas City Royals from Kansas City. They are not proud at 2904 Olive St., his father, Frank Sr. and his mother, Daisie. More like ecstatic. "It's a great moment for him," Mrs. White, 54, said yesterday, putting down the sports section of the local paper, which was hailing the fielding gems of her son. "It's great for all the boys, and it is great for Kansas city. I'm so tense. I'll give you that. It do make me pretty nervous. Sometimes I go to the ball park and I can't even look."

Though Frank Jr., 30, has helped his family financially, his mother and father, who works for a car company in suburban Kansas City, still live in their rather tired, 'if homey, place in the inner city. The sofas and chairs have borne too many bodies over too many years. Odds and ends clutter almost every surface and super market-style paintings hang on the walls.

For some reason, Mrs. White keeps the living room curtains closed all the time, so she was sitting in near darkness yesterday. The only real light came from a gas-flame heater she had turned on, even though outside the day was sparkling and warm.

But the success of Frank Jr. does not go unnoticed. The old wooden fireplace mantle bears eight of his trophies and two baseballs; on an end table is a framed photograph of Frank in a Royals uniform, and on the dining table sits a photo album that chronicles his career.

And the most important fixture is the TV, on which his parents will watch their son tonight from the field at Veterans Stadium. (They won't be in Philadelphia in person, Mrs. White said, "because I don't like airplanes.")

What has happened to their son is sometimes a bit hard to believe. "I didn't think he'd ever make it, I didn't think so," said Mrs. White, a large, polite woman. "I always hoped he would, but I didn't think so."

Of all her six children, Frank Jr. was by far the most athletic, proficient not just in baseball but in football and basketball as well. He'd play catch in the mornings, after school and all day on weekends. He played in Babe Ruth Leagues, neighborhood leagues, anything.

He used to make my daughters so angry because he'd take the heads off their dolls and use them as baseballs," she said, laughing. "They'd come running to me and say, 'Mama, Frank Jr. is doing it again.'"

But whenever baseball scouts came around, they always thought he just wasn't big league material, Mrs. White said. His hands – those hands that now stop rocketing ground balls – just didn't seem quick enough.

But in 1970, he passed a local tryout with the Royals and was sent to their baseball academy in Florida. One day, he found himself succeeding Cookie Rojas at second base.

Though he is a star now, a three- time Gold Glove winner, it has hardly changed him. He is still polite and quiet, just like his parents. Yet, he has not forgotten his old East Side neighborhood. He comes back all the time, often to drop off his three children with his mother while he and his wife go to Royals Stadium for a game.

In fact, after the Royals' stunning defeat Sunday, he came home for some family solace, his mother said.

Being a star in his own right, it seems, is not enough for Frank White Jr. He wants to win the World Series for his home town. But if he doesn't, he won't take it too hard. "At least," his mother said, "they've been to the World Series."

And that is a long way from the Lincoln High bleachers, top row.

How others view this World Series

Howard Rosenberg, Los Angeles Times:

"Be thankful it's NBC and not ABC that's telecasting the Series. You just know Howard Cosell (would) be up there with a pointer in front of a chart analyzing George's (Brett) problem 'Now the green area here...."'

Dick Young, New York Daily News:

"There is much more throwing at hitters in the American League these days than in the National. Beanball watchers attribute this trend to the DH. With pitchers not being permitted to bat in the AL, they run no risk of a reprisal. They can blow a fastball at a hitter's head and not worry about going up there to face the music in an inning or two. The current World Series is being played under the AL rule of the designated hitter.

"The old time ballplayer had a long memory. He would wait a year, sometimes two, to get even for a teammate. That was the code of the hills then. The pitcher was expected to protect his teammates. If any of them were thrown at, it was the considered duty of the pitcher to show the opposing team a bill was due.

"Some knockdown artists are legend. Early Wynn had a reputation of being so tough he'd throw at his grandmother. He was asked about it once and said, 'Why not, she was a pretty good hitter!'"

Thomas Boswell, Washington Post:

"Before the game (Sunday), an usher came up to (Darrell) Porter with a bat and said, 'Darrell, I asked you for this bat as a present on June 2, when you were hitting.333. I thought you might like to have it back.' Porter swung the bat, liked it, and broke his lfor-20 postseason."

Dan Shaughnessy, Washington Star:

"Were this a movie, the handsome (Dallas) Green undoubtedly would kick sand in (Jim) Frey's face and get the girl.

"The finish probably will be something like that. The Series will end, champagne will flow, Green will retire in a blaze of glory and Jim Frey will adjust his glasses and talk about next year. Green says goodbye and Frey says hello."

Tom Callahan, Washington Star:

"The most singularly unattractive, unappealing and, besides that, obnoxious baseball team of modern times is about to win the World Series.

"How to win one more game from Kansas City isn't what's worrying the city fathers of Philadelphia. How are they ever going to get the players to come to the parade?"

Pat Livingston, Pittsburgh Press:

"If there is one thing that distinguishes this World Series from some of those which precede it, it is that this, unfortunately, is a battle of nobodies.

"It's not, I mean, that the players who are in it don't deserve to be here, for they do. In the cauldron of competition, they proved over the long haul that they were the best in their leagues.

"But really, who are they?"

Mike Lupica, New York Daily News:

"After two games, this did not seem like much of a World Series. Now it can be something fine. Personalities have come forth, and two teams have offered us drama that does not involve George Brett's hemorrhoids."

Jim Hawkins, Detroit Free Press:

"The Royals, you see, are Middle America's team. Bibbed overalls and John Deere tractors and straw hats. As far as their fans are concerned, Philadelphia is in the Far East. 'We're playing for milk and ice cream and everything that's right,' quipped (Clint) Hurdle."

Red Smith, New York Times:

"No matter which team wins the championship of North America, it is a simple fact that the Phillies would not be contenders without the 39-year-old millionaire (Pete Rose) who, after 18 years in the major leagues, remains the most devoutly single-minded baseball player on earth.

"Pete Rose has an almost lascivious love of baseball. He plays with total, intense dedication, relishing every moment. At bat he crowds the plate in a knee-sprung crouch, his tough face regarding the pitcher from the middle of the strike zone. The face looks like a detour on Interstate 95, and it wears the fixed, wide-mouthed grin of a cat crouched over a mouse saying, 'Shall I play with him a little longer or eat him up now?' "

Bob Verdi, Chicago Tribune:

“The Philadelphia Phillies long have been detested for their overbearing arrogance, their princely lifestyle and their whimpering ways.

"As more than one opponent theorized, however, it was difficult to hate their guts. You couldn't, after all, hate something they didn't have.

"But the new Philadelphia Phillies, the Phillies who beat the Kansas City Royals 4-3 Sunday to move within one victory of a World Series title, are different. Arrogant still, maybe. But gutless, definitely not."

It’s a different time and place, but it’s the same old Phillies

By Mike Stanton, Associated Press

WORCESTER, Mass. – While the Phillies aim for their first world championship, the memory of their forerunners who played in Worcester 100 years ago is buried under autumn leaves.

In a sleepy park in this central Massachusetts city, children scamper through piles of leaves near the site where the original Phillies played their first baseball game.

Most people in Worcester have forgotten that the team ever existed.

"There's not that much local pride about the Phillies being in the World Series, because nobody realizes they started here," said Ralph Colebrook, 70, who grew up in Worcester.

"The only reason I know of them is because my father used to go to their games and told me about them."

The club entered the National League in 1880 as the "Worcesters" and became popularly known as the Brown Stockings during its three-year stay in town. The roster included names like Hick Carpenter, Buttercup Dickerson and Lip Pike.

Reminiscent of the Phillies, the Worcesters had a manager who accused them of being quitters, and a leftfielder whose fielding was not highly regarded. And, in the best Phillies tradition, the Brown Stockings could be incredibly bad or, occasionally, surprisingly good.

The team was born in Worcester amid controversy that the city wasn't large enough to support a big league franchise. National League president William Hulbert allowed Worcester to include the suburbs in its population count, giving the city the 75,000 people required for a franchise.

But after the 1882 season, league officials moved the Brown Stockings to Philadelphia because they weren’t drawing well, and also to compete with a team started there by the rival American Association.

The Brown Stockings burst onto the big league baseball scene with a flourish. They beat the Troy Trojans (later the New York Giants), 13-1, in their 1880 opener, and after one month of the season were in second place, chasing the Chicago White Stockings (later the Cubs).

The Worcesters reached the height of their existence on June 12, 1880, when John Lee Richmond, fresh out of Brown University, pitched the first perfect game in major league history. Richmond retired 27 straight batters as Worcester nipped Cleveland, 1-0.

From that point, though, it was all downhill for the Brown Stockings. They slumped to a 40-43 record in 1880, fifth in the eight-team league, and followed that with last-place finishes, with 32-50 and 18-66 marks, the next two years.

The final season was especially dismal. The team went through three managers. In September, they committed 21 errors in a single game.

One of the managers. Tommy Bond, accused the players of giving up. The leftfielder, Frank Mountain, was blasted in one newspaper account as an inept fielder who was charged with no errors "because he missed no balls that he touched, but he missed touching a number of which any regular fielder would have easily captured."

Finally, on Sept. 29, 1882, the Brown Stockings bowed out of Worcester with a 10-7 loss to Troy. Only 18 spectators showed up.

Second-guessing, gloom pervade Royals after Game 5

By Larry Eichel, Inquirer Staff Writer

The Kansas City Royals understand the seriousness of their predicament.

"Our backs are against the wall," said Dan Quisenberry. "The Berlin Wall...East side."

They know they must depend on an unreliable young pitcher, Rich Gale, to beat a rested Steve Carlton if they are to force a seventh game.

"If Walter Johnson was pitching for them, it would be tougher," Quisenberry said. "Never saw him, but rumor has it he had good stuff."

But the most difficult part of the Royals' task may be to forget about Sunday's bitter 4-3 loss, a loss that turned the normally serene Kansas City clubhouse into a quiet covey of second-guessers. The Phillies' ninth-inning heroics aside, this was a game that was lost every bit as much as it was won.

The Royals were not exactly on the verge of a clubhouse revolt Sunday evening. But neither were they filled with the overwhelming sense of unity and common purpose often attributed to them – in contrast to that other team.

Perhaps it was just that there was so much for the players – and everyone else, for that matter – to second-guess, so many decisions by K.C. manager Jim Frey, all of them defensible, that didn't work out as planned.

Starting pitcher Larry Gura was angry at Frey because, for the second time in the series, the manager had given him a quick hook. As he had done in Game 2, Frey removed Gura, his most effective starter, even though he had given up only two runs, still had the lead and appeared to be quite strong. And for the second time, Quisenberry, the reliever summoned to replace him, let Gura's win get away.

"I wasn't the least bit tired," Gura said. "I didn't have a chance to argue.... There are some things I'd like to say."

Frank White and several other Royals were second-guessing third-base coach Gordy MacKenzie, who, when the Royals were rallying to take the lead in the sixth, sent the slow-footed Darrell Porter home on a one-out double to the base of the wall in right. Porter was gunned down at the plate by the Phillies' familiar McBride-to-Trillo-to-Boone act, snuffing out the Royals' chances for a very big inning.

"I don't think he should have been sent," White said. Some of his teammates went along with White; others agreed with Frey that they were in no position to question MacKenzie's judgment after the fact.

Clint Hurdle, hitting.417 for the Series, was distraught that Frey, playing the lefty-righty percentages, sent the recently acquired and little-used Jose Cardenal up to bat for him in the seventh against Tug McGraw, even though McGraw's screwball is less effective against lefties than righties. Cardenal flied out to center.

"It broke my heart," Hurdle said.

John Wathan, who hit.305 on the season but is in a deep postseason slump, was not pleased when Frey, with the bases loaded and two out in the ninth, chose to keep him on the bench and let Cardenal have another shot at McGraw. Cardenal, as the world knows, struck out, looking overmatched in the process.

"I'm still here," Wathan reminded reporters.

And Pete LaCock, the backup first baseman, could not have been pleased to find himself on the bench when the inning opened. All season, when the Royals had a late-inning lead, Frey would take out his hulking, shaky-fielding first baseman, Willie Aikens, and put in LaCock, who has led the American League in glove work on several occasions. If that substitution ever seemed appropriate, it was Sunday, when Aikens' defensive lapses had already cost one run and nearly cost several more.

But Sunday, Frey made the same decision Danny Ozark made in the 1977 playoffs against the Dodgers when he kept Greg Luzinski in left rather that put in Jerry Martin for defense. Frey opted to keep his slugger in the field and his glove man on the bench – wanting, as Ozark had wanted then, to keep the slugger's bat in the lineup for the bottom of the ninth. And Frey, like Ozark, had to pay the price as Del Unser ripped a grounder past Aikens that LaCock might have at least knocked down.

Frey's postgame decisions didn't help morale, either.- He announced that he would start Gale in Game 6 rather than veteran lefthander Paul Splittorff, who won 14 games this season, 64 games in the last four years and 137 lifetime – 101 more than Rich Gale has ever won. Frey's reasoning, based on scouting reports, is that it is more prudent to throw righthanders against the Phillies.

So the hopes of the Great Plains rest on Gale, who hasn't won a game since Aug. 23, who has bursitis and tendinitis in his pitching arm, who won 12 starts in a row at midseason mainly because the Royals scored in bunches whenever he pitched. This is the same Rich Gale who struggled through four-plus innings against the Phils Friday night, barely escaping disaster time after time.

"They should have scored more runs off me for all the opportunities they had," said the red-bearded, 6-foot, 7-inch, 225-pound righthander. "But I felt like I made some pretty good pitches at times, too.

"It's not like I'm the only person who matters out there," he said. "Obviously, if I do not perform well, my teammates will not have the opportunity to makes the big plays or make the clutch hits. If I don't do well and we lose, the sun will come up tomorrow....

"I said before the Series that I thought we would have to beat Steve Carlton one ball game to win the Series. We'll have to do it Tuesday night."

The ace is rested and ready

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

The Phillies' whole season comes down to Steve Carlton tonight. And that is the way it should be. Because without Steve Carlton, the Phillies wouldn't be here for the season to come down to him.

The Carlton numbers are familiar by now – 24-9, 2.34, 304 innings pitched, the most strikeouts on the planet (286).

Even the less-familiar Carlton stats have been bandied about a billion times – the 16 starts in which he allowed one run or less, the 14 times he won following Phillies defeats, the 14 runs the Phillies got him in his nine losses.

It is all part of the lore of a Phillies season that gets more remarkable every day. And Carlton can make that season the most remarkable of all if he can just beat the Royals and Rich Gale in Game 6 of the World Series tonight.

Carlton is capable of winning this game nearly all by himself. If he could just spin one of those 11-strike-out near-no-hitters he was twirling about every other start in June, this World Series would be history.

However, it won't be the Steve Carlton of June who will be showing up at the Vet tonight. The Carlton pitching tonight is the much wearier October edition.

The Carlton pitching tonight will be a guy who has worked more innings than any other pitcher alive.

It will be a guy whose three postseason starts have not been especially overpowering.

It will be a guy who hasn't been himself – not really – for better than a month now.

"I think probably, over the last 10 games, maybe only in six out of the 10 have we seen Lefty pretty close to the Cy Young guy we watched all year," said Dallas Green. "But even in the four where he had less than his best stuff, he certainly kept us in the game. That's what makes him a great pitcher.

"I don't even think Lefty had that good stuff the last time he faced Kansas City (a 6-4 victory in Game 2). But he struck out 10 people, so he must have had something. Lefty is capable of doing that."

He's capable of it, but he also is a tired pitcher. He has won two of his three starts in the postseason. He did strike out 10 Royals in one of them. He did hold the Astros to one run in another.

But he also got knocked out before the sixth inning in the other, the first time that has happened this year. And he has labored. The stuff that is there one inning is not always there the next. He is just a hair off, the slim difference between overpowering and just tough.

"I think you can tell in arm speed," said Green. "He doesn't have the quick arm he had earlier. And as a result he doesn't have the extra pop he needs on his fastball or that he needs on his slider.

"When he was fresh, early in the season, he had the great arm speed, and everything was crackling. Now they're not crackling as many times in a row. But they're working enough to get the job done. And that's all he and I care about."

Carlton's record since Sept. 1 reflects the subtle difference in his stuff.

You don't see it so much in record or earned-run average. In 31 starts through Sept. 1, Carlton was 21-7, 2.30. In his 10 starts since (counting the postseason), he is 5-2, 2.53.

But he allowed more than three earned runs only three times in the first 31 starts. He has done that three more times since. He had 10 or more strikeouts in 10 games before Sept. 1. He has done it only twice since.

He has pitched only one complete game in his last seven starts. He blew a lead of more than two runs for the first time all year. He simply has not quite been the same. But then, after 324 innings, how could he be?

Green took that into account when he decided to pitch Carlton tonight. He could have started him in Game 5 Sunday. But Carlton had thrown 159 pitches in his previous outing. And Sunday was only four days later. So Green decided to save him and take his chances with Marty Bystrom.

"I just think, the way those 320 innings have added up, that Lefty needed this extra time," Green said. "I think Lefty would have pitched whenever I told him to pitch, but this extra rest should just do him a world of good.

"I said earlier that I could possibly use him 2½ times in the Series if need be. But I would have had to pitch him (Sunday) to do that. And I still felt that if I got everything I expected out of Bystrom, we'd be OK."

It worked out more than OK. It worked out so the Phillies only need to win one of two games. And they have a rested Carlton to work one, a rested Dick Ruthven to pitch the other tomorrow if they need him.

"We are," said Green, "in the perfect spot."

All Steve Carlton has to do now is just be Steve Carlton.

...and so is the ace in the hole

By Frank Dolson, Inquirer Sports Editor

He is the Phillies' ace in the hole, the man who is waiting in the wings in case the Kansas City Royals force a seventh game in the 1980 World Series.

Dick Ruthven fervently hopes there will be ho tomorrow at the Vet, but if there is the 29-year-old righthander who underwent elbow surgery a year ago is ready and willing and downright determined to pitch.

"You're most likely the seventh-game pitcher, aren't you?" a Los Angeles writer asked Ruthven the other day in Kansas City.

The answer came quickly and with feeling. "I am the seventh game pitcher or I will shoot somebody," Dick Ruthven said.

He had expected to be the fifth-game pitcher in the National League championship series and was more than a little upset when he wasn't handed the ball. Instead Ruthven wound up in the bullpen, where he warmed up in the early innings… and was bypassed again.

He has become a very calm, cool, poised professional, but that Sunday night in Houston, when Larry Christenson got the call in the seventh inning of a 2-2 game, Ruthven was an extremely angry young man.

"I got mad when they brought Larry in with one day's rest," he said. "I'm saying, 'What the hell is this – a sacrificial lamb? I've got more rest. Why don't you use me?'"

They finally did use him – with the score tied, 7-7, in the bottom of the ninth and the season on the line. It had been a terribly difficult few hours for Dick Ruthven, watching the first eight innings of that game, wanting to get the ball, wondering if he ever would.

"I was emotionally spent," he said. "I had never seen a game or participated in a game which had so many comebacks, so many disappointments, so much elation, then another disappointment on top of that."

And yet, when they finally did hand him the ball in a situation where one slip, one bad pitch could end the Phillies' season, he was in total control, mentally and physically. That, in itself, was a remarkable achievement and an indication of how far he has come as a pitcher and a person.

"By the time I got out there," Ruthven said, smiling, "I was a robot, which is exactly what I wanted to be."

He retired the Astros in order in the home ninth and then, after the Phillies went ahead on Garry Maddox' two-out double in the top of the 10th, he retired the Astros in order again.

All around him that night hearts were pounding, stomachs were churning. Yet Ruthven remained amazingly calm, cool, collected. It was a superb demonstration of a young man's ability to concentrate under the most difficult circumstances.

Dick Ruthven wasn't always able to fight off the distractions, the disappointments, the emotional highs and lows that are so much a part of pitching for a living. But he has learned. It wasn't easy. There were some difficult nights in Toledo, pitching for the Phillies' Triple-A farm club five years ago, and in Atlanta after that, but instead of destroying him, they toughened him until now he is able to give every game – even the fifth game of a championship series or the seventh game of a World Series – his best effort.

"I try mentally to make them all the same," he said. "I've been able to do that so far. I do a lot of mental homework to try to prepare myself to be that way…. I think the thing that makes it easier to be calm is to go out there with the idea that all you can do is as good as you can do.

"If you've prepared yourself physically and mentally to do the best you can do and it doesn't happen to be good enough, there's no reason to get eaten up with it, and there's no reason to get nervous and try harder and try to be somebody you're not just because it's a World Series."

The ability to master that approach has made Dick Ruthven the pitcher that he now is – one who seems almost unflappable. If you knew him in his younger days, you can understand how far he has come.

"I couldn't have done it when I was younger," he said. "Learning how to control my mind, to channel it in a positive direction instead of the negative ones you can dwell on was the toughest thing for me."

It was tough because he is an uncommonly intelligent young man with a tendency to think things through too carefully, too completely, to worry about things that merely cluttered his mind and made concentrating on the task at hand that much more difficult.

"At times," Ruthven said, "I almost wish, that I was born a moron so I wouldn't think so much. I know I've thought about that. I know now the fact that I'm not a moron is an advantage once I was able to channel my thoughts... it just took me a long time to sort it out."

But he did sort it out. He conquered his own No. 1 enemy – himself – and the result is the kind of pitcher, the kind of ace in the hole that the Phillies are fortunate to have – in the event there is a tomorrow at the Vet.

The new Mr. October

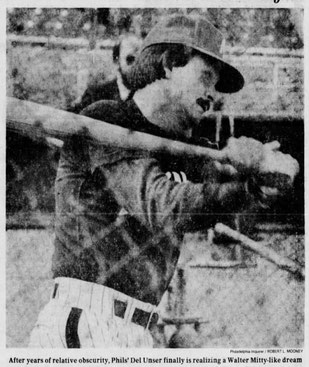

The heretofore secret life of Del Unser is in limelight

By Bill Lyon

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

So, it turns out, there really is some justice after all.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

The faithful employee who never makes waves, never calls in sick, never grouses about overtime, finally gets the big promotion.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

The guy down the block, the one who mows your lawn while you're away, who lends you his car when yours is in the shop, wins the Irish Sweepstakes.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

The guy who stops when no one else will, when you're marooned on an interstate looking forlornly into a smoking engine; the guy who lets you in front of him in the supermarket line, he just hit the millionaire's lottery.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

Are you watching, Leo Durocher? Catch this, because a nice guy is finishing first.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

Well, why not? Isn't it about time? Do all our sports heroes have to be overbearing, arrogant super-sulks? Must we always have to endure haughty, overpriced egomaniacs who snub the media, resent the fans and are jealous of their own teammates?

No, this time around, the gods of baseball have chosen to deliver us from the hands of brooding, surly, one-dimensional temper tantrums, and they have, instead, reached out and anointed an unassuming 35-year-old journeyman pinch-hitter who had spent 13 plodding, largely undistinguished years playing a game for a living.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

It is a time for Joe Average to rejoice.

In the measured madness of the playoffs and now in the numbing frenzy of the World Series; a genuinely nice man, after a lot of obscurity and anonymity, suddenly finds himself a hero.

Delbert Bernard Unser, sometimes an outfielder, sometimes a first baseman, sometimes a real estate salesman, has had roughly 5,100 official at-bats in the major leagues, and the first 5,090 went mostly unnoticed, incidental lines of agate type no more meaningful than the listings in a phone directory in a town where you've never been.

But in the last two weeks, one of the spear-carriers has become the star. It is like one of Sinatra's back-up singers doing solos, and bringing down the house.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

For a dozen years, he played on teams that began each season with little hope and ended them with even less. The Washington Senators. The Cleveland Indians. The Phillies (in ‘73 and '74 when they were a sub-.500 team). The New York Mets (when they were not amazin' but simply atrocious). The Montreal Expos (before they became contenders).

A man accumulates a lot of scars that way, not necessarily all of them the kind that show. But you learn some things, too.

"Patience, mostly," said Del Unser. "And perseverance."

There is a point, however, in an athlete's career when persevering becomes simply stubbornness. The road down is a familiar one... from starter to utility man to pinch-hitter to see ya later. A lot of people thought Del Unser had reached that final stop. None of them, however, happened to be named Del Unser. He became a free agent after the 1978 season and seven teams drafted him. None, however, called him. Silence can be the loudest rejection of all.

It has since been chronicled how Del Unser all but begged his way back into baseball.

"Playing even part-time still beats the heck out of not playing at all," he said.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

Now he finds himself inundated by a tidal wave of media. And they, in turn, encounter something rare in a Phillie, someone who is gracious, cooperative, courteous, available, accessible, who will patiently retell his life story for every ink-stained wretch from Pocatcllo to Passyunk.

"There weren't too many who ever bothered to ask before," he said, smiling. "Not that they had any reason to."

He wears it well, the sudden fame and adulation, and he maintains an even emotional keel, and in all the swirling clamor he has managed to maintain his perspective. He has always had grace and class and dignity, but our eternal weakness is that we must talk only to winners, so the Del Unsers of the world too rarely get invited to the interview room.

"The difference between what's happening now and what happened before is about this much," he said the other day, holding up a thumb and forefinger, with only a tiny space separating them. "If I hit the ball right at somebody, then you're talking to someone else."

There is a bemused smile tugging at the corners of his mouth. He knows there is no rhyme or reason to all of this. There never is.

Sometimes, October belongs to those with a natural flair, an innate flamboyance, to those who lust for the spotlight, to a Ruth, to a Jackson. Sometimes, October belongs to a man who has it thrust on him, suddenly, inexplicably, and so a cigar-chewing pinch-hitter named Dusty Rhodes becomes a part of autumnal folk lore; a pitcher named Don Larson, experimenting with a no-windup delivery, throws a perfect game.

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

None of it makes sense. It never does. Del Unser knows this, appreciates it, and hence remains a pragmatist at heart, slightly amused at what the gods of baseball have done to him.

There had never been any hint, any reason for him to believe he would be singled out.

"Don't take this the wrong way, but, really, it's almost been something of a religious experience," he said. "I mean, what's happened, sometimes it's almost mystical. But then I think of all the years, all the teams, all the hours in the batting cage, all the help I've had from people like Billy DeMars and... well...."

Well, what he was saying without saying is that mysticism doesn't help you hit the 0-and-2 slider down and away.

He is a man who spent a career waiting. Waiting to be on winner. And now, waiting on the bench until Dallas Green turns his head and barks, "Del!" Before this season, there were 1,622 major league games of waiting and 5,032 at-bats of waiting.

Now it is a measure of Del Unser that he is happiest for the people who are happy for Del Unser.

"Through all the teams, all the traveling, we've met a lot of people, and now they're sending us telegrams and letters," he said. "There are stacks of them. I may just paper the walls of one room with them when this is over. What they say is that they're glad for us. Well, I'm glad for them."

Does this, then, make all of what preceded worthwhile?

"Frankly, no," Del Unser replied. "I know what you're getting at, but I wouldn't have had any regrets about my career if it had ended without this.

"There was something I wanted to do (play big-league baseball) and something I thought I could do, and I got the chance. That made me very fortunate because there are a lot of people who have dreams but never get the opportunity to chase them.

"And now I won't have to spend the rest of my life wondering if I could have done it. That's the saddest thing, wondering if you could have done something and never getting the chance to find out. That hurts worse than failing."

And Del Unser is the new Mr. October....

Today is the day Phils can win it all

Carlton faces Gale at the Vet

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

Here comes a sentence you have never read in any newspaper ever before: By the time today is over, the Phillies may have won a World Series.

They play the Royals in Game 6 of the Series tonight (Steve Carlton vs. Rich Gale). They lead this thing, three games to two. They only have to win tonight and they will be world champs.

You probably have grasped that by now. You probably have heard it enough that you have accepted that fact. Yet, you have to remind yourself of something – this is the World Series, the actual, honest-to-goodness, real live World Series.

The Pirates aren't here. The Yankees aren't here. The Dodgers and Orioles and Reds aren't here, either.

All the teams that always have been in this position in the past aren't here. Only the Phillies can win the World Series tonight. Not even the Royals can do that tonight. They have to win tonight only so they will get the chance to try again tomorrow.

But the Phillies have more than that going for them. They also have history, their home town, their best pitcher and the law of averages on their side. They have so many things on their side, in fact, there has to be a catch somewhere.

There is. The catch is that they still have to play. They still have to win one game.

"All the talk doesn't mean a damn thing," Mike Schmidt said during the final off-day workout of the Phillies' longest season yesterday. "It only makes for good print, good interviews.

"There's no feeling of momentum or any of that. Neither team has any more confidence than the other team. I guarantee you, if they (the Royals) were sitting over there only having to win one, there's no way they'd have us out-confidenced.

"Once the teams are introduced and they play the national anthem and we go back to the dugout, none of that means anything. It's possible it might affect a play here or there. It's possible that somebody might take a chance or make an aggressive play as a result of there being no tomorrow. But maybe not. It may make a difference in the ball game. It may not. But that's the only way any of this would have an effect."

It is just one game, when you get right down to it. None of the talk or the history or anything else can affect that. The way things look doesn't matter. That's what Schmidt was saying.

The pitching matchups look good, but the matchups have looked good before. Gale hasn't won for the Royals in eight weeks. But he was matched up with Dick Ruthven in Kansas City last Friday, and the Royals won, even though Ruthven out-pitched Gale by any measure you use. Tonight, Gale is matched against Carlton. But the Phillies have lost games with Carlton pitching before. They lost one three weeks ago in a similar situation, in fact.

One night earlier, they had beaten the Expos in the ninth inning of the opener of a three-game series at the Vet. They needed to win only once more to take that crucial series. But Carlton lost the next day, and the Expos won two in a row.

It can happen. The Phillies have seen enough sure things slip away over the years to know what can happen. It is important that they not forget that now.

"We're one game away now, but we've been on the other side of that fence," Dallas Green said. "We had to do just what they (the Royals) have to do at the (playoff series in Houston). We had to sweep two in their ballpark, and we did. They have to do the same thing. So we know it's possible.

"We have to stay within ourselves. We have to do our own thing and not get too cocky or happy with ourselves until the job is done."

Green was asked if he had talked to his players about this, whether he had reminded them. The manager smiled and shook his head.

"I don't think this team needs a lot of reminders," he said. "We've gone through too many things ourselves. We know what's possible."

The manager has been part of the Phillies organization for 25 years. He was a member of the '64 Pholdin' Phillies. Sure, he remembers. But his players were there for the three playoff series that got away. They remember pretty well, too, you might say.

"We just have to be aggressive," Larry Bowa said. "We can't think we have them with their backs against the wall. If they win (tonight), whose back is to the wall then?"

You have heard these words come out of their mouths before. But those words haven't been about the World Series. That is why you sometimes have to remind yourself just what is about to happen here.

"The first couple of games of this thing here at home, it didn't feel like the World Series to me," Keith Moreland said. "It felt like a big game in the Montreal series or something.

"It didn't really seem like the World Series until we went away from home. Then you're in a park you've never seen before. There are so many more media around. You see people you've never seen before. Then it started to feel like something different."

Moreland is a rookie, though. He didn't live through the Phillies' haunted past. Last year, he said, he got excited just watching the Pirates in the World Series and knowing he had actually played against the same Pirates in September.

Schmidt, on the other hand, has been through it all. He has had to watch a lot of World Series on TV, knowing that he had just played the same Dodgers or Reds in the playoffs.

"The other years, I always tried to talk myself out of watching it," Schmidt said. "But I always did. And I always thought, 'One break here or there, and we'd be there.’

"And that's the incredible thing about this. You think about that Los Angeles team or that Pittsburgh team or that Montreal team or that New York team or that Baltimore team that won 100 games – they're all watching this thing on television now. And I know what they're feeling. They're feeling, 'I don't want to be in this chair next year watching the World Series. I want to be in it.'"

The Phillies are in it now. That is - sometimes hard to grasp. They are one game away from winning it all. That is even harder to grasp.

Maybe that is the whole idea of being in the World Series. You just win it while you can. You grasp it later.