Kansas City Times - The Series Comes to KC - Oct. 17, 1980

Photos

Being involved is enough at World Series time

The Morning Line By Mike McKenzie

Whether 90 million people see it, or 50 people see it, the World Series Is the ultimate confrontation.”

— Dan Quisenberry, Royals pitcher

"You realize as you go on, getting there is only part of the story. The next story is winning the World Series. The big story."

— Jim Frey, Royals manager

"Later, when you're telling your grandchildren about it, it'd be a lot better to say you won. But it 'll be a happy memory, one way or another.”

– Dennis Leonard, Royals pitcher

Kansas City is going for the big story. Stacking the memories atop a heap of frustrating past filled with losing, struggling, and barely missing.

Kansas City, through its Royals, is smack in the middle of the ultimate baseball confrontation, against a team from the city that gave Kansas City major league baseball in the first place — Philadelphia.

At first, those A’s were horrendous. But the city backed them. The reward: just when the A’s got good, they and the donkey they rode in on, both named Charley O., were moved to Oakland.

The city was too good to remain a baseball ghost town. The Royals spun from the cocoon. At first, those Royals were horrendous. But the city backed them. The reward: just when the Royals got good, the Yankees smothered them. Once, twice, three times a bummer.

Then came Royals ’80. Different shade of dawn. The Yankees could be had. And were. A karate chop to the windpipe. Celebrate, celebrate. Up from the smoke and ruins of hope dashed so many, too many times, Kansas City celebrates. Listen to the music.

For so long, the people of Kansas City bad wondered. What's to celebrate? Rich Gale's sore arm? Paul Splittorff’s sore back? Larry Gura's and Dennis Leonard’s gopher pitches? Darrell Porter's anemic batting? Clint Hurdle's partial disappearance from his rightful spot? Hal McRae's and Frank White’s discontent and trade pleas? George Brett’s sore hand?

Another whupping by the Yankees? The mere thought was enough to make a Hallmark card frown.

Brett’s flirtation with .400 was enough to hang a heart on all summer, but not enough to make another frigid winter toasty.

Let it be. The big story.

And maybe that — victory in the World Series — isn’t even necessary. (Easy to say when you’re two down.) Maybe it's enough to have whipped the Yankees, to have arrived at the ultimate confrontation.

There is a measure of cop-out to that resignation, to be certain. As Frey said, “Something to cherish is to be on the team that is called the best in baseball.” Happiness rushes the soul in degrees.

But as Leonard mused, can the memory of being there be bad even after losing? Hardly.

A long-hungering community — part of it tightly woven, vocally, spiritually, within the tapestry of Royal-mania, part of it caring only from the fringes — long will drink from this memory.

Kansas City, through its Royals, arose before the nation during its recess for the national pastime. Touch me, feel me, see me. The Philadelphia Inquirer sent a reporter to our city to capture its mood, and his report was headlined ”…Wants to be Known as More than a Cowtown.”

Mainly, Kansas City wants to be known, period, and a Royal Blue baseball team is suddenly a vehicle for renown.

The Super Bowl victory of 1970 wasn’t enough; it was played in New Orleans.

It's difficult to measure the impact of a showcase sporting event on its community. It’s difficult even to measure the boundaries of the community. Calls have rung in from Ogden, Utah, and from Iowa, from Freeport, Ill., from Wichita to Topeka to inquire about tickets to see their Royals.

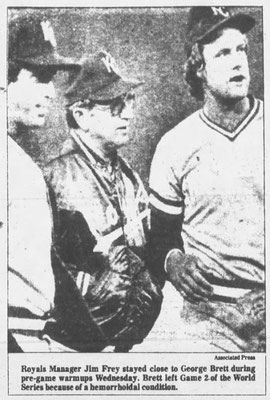

Concerned citizens from California, Texas and Utah telephoned the sports department of The Star & Times to offer advice — Kingsford corn starch at 49 cents a box, sucking orange peels, etc. — to cure George Brett’s hemorrhoids.

In Philadelphia, the euphoria of the World Series sweeps aside a deprived sporting history of worse despair than Kansas City ever dreamed of. Another community, another impact.

The big story may be winning. But the whole story is big enough. Two sides, two teams, two peoples are saluted for arriving, and there should be no firing squad for the vanquished.

The Royals don’t need to panic – just perform

By Mike Fish, A Member of the Sports Staff

If the Royals wanted to panic, they could call in all their scouts and advisers for a closed-door session. Just analyze Games 1 and 2 of the World Series and issue a directive.

Make it something simple — "Win or else."

The Royals don't need the pressure. They already know the score. Twice they have grabbed an early advantage only to have the Phillies take it back.

In Game 1 it was 20-game winner Dennis Leonard against rookie Bob Walk. It was a game the well-rested Royals figured to win, but didn’t.

Then, in Game 2, ace reliever Dan Quisenberry couldn’t hold a two-run lead. The Phillies won 6-4. So the Royals take to the field tonight, down two games in the best-of-seven series.

"I thought we were gonna win last night,” said reliever Ken Brett. “If we'd have beat them last night they'd have come in here on the defensive.

“We scored enough runs both nights to win, but once we got the lead we couldn't hold it. Part of the reason is because of guys like (Keith) Moreland and (Del) Unser."

The scouting report before the series was to pitch carefully to the big bats of Mike Schmidt and Greg Luzinski. Make a mistake and they’d call you. But the key blows haven’t come from Schmidt and Luzinski.

Schmidt did uncork a 2-run double in Game 2. But Bake McBride, not known as a power hitter, had a 3-run homer in Game 1. And No. 9 hitter Bob Boone was 3-for-4 with two doubles and two RBIs.

"Ihey’ve got a good enough lineup that you can’t overlook anyone," said catcher John Wathan. “You have to expect that from a club that’s come this far.

“Larry (Gura) pitched a real strong six innings last night. Quiz got hit pretty good, but they were hitting some good pitches. He just didn’t have quite the velocity.”

With the series shifting back to Royals Stadium, the Phillies won't have 65,000-plus screaming Veterans Stadium fans behind them.

"Having our fans will help,” said Wathan. “'It didn’t bother me that much because I think we’re used to playing in Yankee Stadium. But it has to be an advantage to get back here. The key is beating them in Game 3, cutting them down and maybe sweeping them three straight here in our ballpark.”

The Royals' lineup is expected to be the same as the one which faced righthander Bob Walk in Game 1. Clint Hurdle will start in right field, and Darrell Porter will be behind the plate.

There is also a strong possibility that George Brett will be able to open the game at third. Brett, 2-for-2 with a walk, took himself out of Game 2 after five innings. His hemorrhoids were lanced Thursday at St Luke’s Hospital.

"If George feels like he can play, the doctor (Dr John Heryer) said it was OK,” said Mickey Cobb, the Royals' trainer. "The main thing is that the pain is relieved. That was his problem in last night's game.”

"I think he's got a good chance to play,” said his brother, Ken. "I saw his doctor and he said he’d probably be OK to play.”

Phillies trying to erase long history of frustration

By Jack Etkin, A Member of the Staff

William Penn, whose statue stands atop Philadelphia's city hall, used to face north giving him a view toward Connie Mack Stadium. But, one day, according to local legend, the Phillies botched a double play ground ball, and Penn, no longer able to endure the torture, turned away in disgust.

Give up on the Phillies? That gilded franchise which draws nearly 3 million fans every season and has won four National League East titles in the last five years?

But probe the past and the Phillies become a monument to futility and frustration: three pennants in 97 years and decides spent languishing at the bottom of the league.

Between the pennants in 1915 and 1950, the Phillies were mired in baseball's nether world, escaping the second division only four limes. During 24 interminable seasons, a league record, the Phillies grew moss in the National League cellar.

Failure also has come in shorter bursts. The 1961 team lost 23 straight games, a major league record. The 1964 Phillies, in first place for 73 days, had a 6½ game lead with 12 games to play. Amazingly, the team lost 10 straight games and expired in the final week of the season.

The roots of that historic collapse may be traced to the first National League game ever played. On April 22, 1876, the Philadelphia team, a financial ruin which disbanded later that year and returned as the Phillies in 1983, gave up two runs in the 9th inning arid lost to Boston, 6-5.

The Phillies began the slow climb from mediocrity to respectability in 1911, when rookie pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander won 28 and lost 13 for a fourth-place team. The team’s first pennant came four years later, but after winning the opening game of the World Series against the Red Sox, the Phillies lost four straight.

The fabled Alexander won 63 games for the second-place teams of 1916 and 1917. But owner William Baker a former New York City police commissioner, traded Alexander to the Cube in 1917. That deal brought the cash-short Phillies two players plus $60,000, but started the team on its steep slide into the second division dungeon.

Between 1917 and 1948, the Phillies annually played below .500, except for the 1932 team, a fourth-place anomaly which sneaked two games above that break-even level.

Some years the Phillies seemed jinxed. In 1930, their team batting average was .315, a franchise record, but pitching, the commodity that wins games, was a bittersweet mystery.

Phillies' pitchers surrendered 1,199 runs and the staff's earned run average was 6.70, both major league records which might endure forever. Eight Phillies, including sluggers Chuck Klein and Lefty O’Doul, hit above 300 that year for a cellar dweller which lost 102 games and finished 40 games out of first place.

In 1938 the Phillies moved out of Baker Bowl, their home since 1887 but a half century later badly outmoded and in need of repair. Shibe Park, home of the Athletics and renamed Connie Mack Stadium in 1953, became the Phillies' new home. But the plot remained the same.

A last place finish in 1938 began a five-year period of record-breaking ineptitude, even by Phillies' standards, when the team tumbled into an abyss of defeats. For five years, no Phillies team lost fewer than 103 games, and the highest winning percentage was a dreadful .327.

William Baker's ownership, from 1913 to 1930, was followed by the shoestring operation of Gerald Nugent, who owned the team from 1932 to 1942. Nugent sold off players to stay afloat but still fell deeply into debt to the National League, which took over the franchise.

William D. Cox, a New York City lumber baron, bought the team from the league in early 1943, but his was a brief tenure. In November 1943, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis barred Cox from ownership for betting on baseball, an unpardonable sin even though Cox was backing his own sad team.

Robert R.M. Carpenter, Sr., a Delaware millionaire who had worked for duPont, bought the team for $400,000 and provided the Phillies with much-needed financial stability.

The 1949 team finished third, the highest Phillies’ finish since 1917, despite a macabre off-the-field incident.

On the team’s first trip into Chicago in June, first baseman Eddie Waitkus, who had been acquired from the Cubs after the 1948 season, found a note in his hotel room instructing him to go to another room in the hotel. There, he encountered a slim woman whom he had never met.

“I've got a surprise for you," Ruth Steinhagen told Waitkus. The 19-year-old typist then grabbed a 22 caliber rife from a closet and fired a shot into Waitkus' lung. Waitkus, hitting 306 at the time, was critically wounded, missed the remainder of the season and never really played well again.

"I'm sorry Eddie had to suffer so," said Miss Steinhagen, who was committed to a hospital but released three years later. “But I had to shoot somebody. He reminded me of my father. Since 1 shot Eddie, I feel more consoled and relieved than ever before in my life.”

Long-suffering Phillies fans were consoled with a pennant in 1950 when Eddie Sawyer’s Whiz Kids, whose starting team had an average age of 26, fought off the Dodgers on the last day of the season. The glory was short-lived, however, as the Yankees polished off the Phils in four games in the World Series.

By 1958, the Phillies again were a last place team as the Whiz Kids had fizzed.

Gene Mauch inherited Sawyer's lowly team and endured the following season when the Phils lost 23 consecutive games.

Mauch was a notoriously bad loser, who insisted on a somber clubhouse after any defeat. Once the streak hit 20, the mood became positively funereal, and Stan Hochman, now a columnist for the Philadelphia Daily News suggested to a colleague that they “walk into the clubhouse backward so Mauch will think we re leaving."

The Phillies began leaving their losing ways after moving into Veterans Stadium in 1971. Steve Carlton, acquired from the Cardinals for Rick Wise in Feb. 1972, was 27-10 with a 1.98 ERA for the last-place 1972 Phillies. The rest of the pitching staff won 32 games.

But the days of the hapless losers were over. The farm system, backed by the Carpenter's money, produced Bob Boone, Larry Bowa, Mike Schmidt and Greg Luzinski. Paul Owens, the Phillies’ general manager since June 1972, acquired Garry Maddox, Bake McBride and Manny Trillo in trades and signed Pete Rose as a free agent after the 1978 season.

The highly-paid Phillies, bridesmaids under easy-going Danny Ozark, became pennant winners this year under tempestuous Dallas Green. But to those who have been around the team for decades, winning isn’t everything.

“They're the same arrogant, self-centered, mean, unwholesome bunch they were a month ago," said columnist Hochman, a Philadelphia newspaperman since 1949. “I enjoyed being around any number of Phillies teams a lot more than this bunch."

But these boys of summer are in the Fall Classic And in Philadelphia, that occurs only in every other generation.

Carlton plays hide-and-no-seek with reporters

Philadelphia pitcher refuses to answer questions

By Mike McKenzie, A Member of the Sports Staff

Reporters who deal with the Phillies year-round tell of a hide-and-seek experience. Even after big victories, such as when they defeated Montreal to clinch the National League East Division two weeks ago, many players disappeared when it came time for interviews.

With one Phillie, however, every day is hide-and no-seek. He hides openly. Steve Carlton doesn't have to duck into a training room or equipment room. He goes to his dressing cubicle, goes to the shower, goes back to dress, leaves the scene.

And nobody from the media approaches him.

It’s been that way since 1973. After seasons of 20-9 for the Cardinals in 1971 and 27-iO for the Phillies in ’72, Carlton soured and lost 20 in ’73. Along the way, he fell out with reporters and quit granting interviews.

Thus, the man considered the best left-banded pitcher, and perhaps either-handed, in the National League is a virtual unknown personality. The only things really known are whatever traits are visible on the mound and the impressive statistics of his work there.

A man considered to be Carlton’s best friend, Tim McCarver, who was his catcher several years and is now a Phillies broadcaster, says Carlton is one of the nicest men anybody could know — but nobody knows. “He doesn’t care about his public image,” McCarver says.

Apparently, there are no exceptions, either. After the Phillies bounced the Astros two straight playoff games in Houston to rally to the National League championship, a Philadelphia TV sportscaster stuck his microphone toward Carlton.

After nine frustrating years as a Phillie, and possibly his third Cy Young Award season, surely even Carlton would open up in the spontaneous joy that filled the clubhouse.

The sportscaster implored, 'Would you talk now, Steve?”

Carlton turned his back. “It was like I wasn't even there, didn’t exist,” said the sportscaster.

While the Phillies celebrated in Houston, Carlton, his uniform wet with champagne, stood with his wife, her clothing also drenched, and watched with a smile on his face. At one moment, he mouthed, “Beautiful.”

One writer claims to have heard him say, “Great champagne,” during a similar celebration after victory over Montreal.

Another writer, Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post, decided this season to learn something of Carlton by examining his dressing stall. Carlton became incensed and ran Boswell off, saying be had no business snooping in his personal belongings.

Actually, there couldn't have been that much to sniff out. Carlton's dressing stall is relatively barren. On a shelf usually sits a bottle of vitamins and protein supplement, a tube of toothpaste, and nothing more. His area is not cluttered with paraphernalia, like most major league players.

And although several Phillies will tell you Carlton is about, if not the most popular player among teammates, the only Carlton the public gets to share is the one it sees at work and through his comrades' thoughts.

His statistics speak for themselves: 249 victories, an average of 17-plus for every full season in the majors; 20 or more victories five times; nearly 3000 strikeouts (most in history by a left-hander), et al.

As remarkable as any of his numbers are innings pitched. This year he topped 300 for the second time. “After that many innings,” said Dallas Green, the Phillies’ manager, “any man is lucky to still lift his arm up.”

Remarkably, when Houston knocked Carlton out of the game in the fourth game of the playoffs, the 5⅓-inning stint was his shortest of the season.

Bill Virdon, the Astros’ manager, said during the playoffs: “If I had Carlton and needed one win, I'd use him no matter what,” meaning rested or unrested.

"With Lefty pitching (in Philadelphia, rarely are Carlton’s real names used; he is just Lefty) the Phillies are contenders,” said McCarver in Sports Illustrated July 21, 1980. “Without him, they’re a fourth-place club with a losing record.”

In that article, McCarver also revealed a personal side to Carlton — his penchant for elk hunting, devotion to exercise and vegetarian diet, study of Eastern cultures and philosophies, love for wines and dedication to family.

Overtime duty may have taken its toll on Carlton the past month, with the Phillies struggling to catch the Expos, overturn the Astros, and come back twice on the Royals to lead the World Series 2-to-0. He did not display his normal effectiveness in either playoff start against Houston, or against the Royals in Game 2 an Wednesday.

Yet, the Royals also saw the ingredient that keeps Carlton on top at age 35, when other men struggle to stay in the game. “I’ve never seen anybody like Lefty and Pete Rose with such total concentration,' said Bob Boone, the Phillies’ catcher after Carlton held on against the Royals despite giving 11 hits and six walks. “Even after their early hits, he made the big pitch when he had to.”

Carlton induced three double plays grounders which bailed him out of trouble. He also struck out 10.

The Royals’ scouting report indicated batters much be patient against Carlton’s assortment of breaking pitches — a dipping slider and sharp curve. He is especially known for getting hitters on strikes at swerving pitches that end up out of the strike zone.

The Royals took the right pitches against him,” said Boone. “Those that go down and end up balls. But the balls were slick, and he had trouble getting the bite on his slider.”

But, cotton earplugs firmly affixed, as usual, Carlton did get the bite on the Royals. Manny Trillo, second baseman, aired the Carlton syndrome simply, “He’s so good when he has to be.”

Jim Frey, manager of the Royals, drew a good picture of what sets Carlton apart: “He has an extra special ingredient mixed inside him, above the talent.”

Others say it well for him. Carlton says nothing.

Tug McGraw, the team's resident philosopher on all subjects, explained Carlton's and the Phillies’ overall wariness with the press: ‘If you’ve been bitten by a snake, you don’t go playing with other snakes, even if they’re a different kind.”

Two down and… can the Royals pull it out?

Game 1

PHILADELPHIA — Dennis Leonard is a hot-weather pitcher. Always has been — always will be.

This year was no exception. After the All-Star break when the thermometer blew its top, Leonard got hot right along with the weather: 13-4 after the All-Star break, a complete-game victory that clinched the-American League West title.

However it wasn’t hot Tuesday night in Philadelphia — less than 50 degrees. Leonard wasn’t hot, either. It was the bottom of the fourth inning and the Royals had built Leonard a 4-0 lead. He couldn’t hold it.

First, it was the Phillies’ Larry Bowa, who singled over second. Unexpectedly, he stole second. Bob Boone followed with a double to left. Lonnie Smith singled. Pete Rose was hit by a pitch. Mike Schmidt walked. Bake McBride homered.

Five Philly runs – good-bye Leonard.

“I couldn’t get my breaking pitch over worth beans tonight,” Leonard said dejectedly when it was over – and the Phillies had a 7-6 victory. “I got behind and had to go with my fastball, and they hit it.”

Granted, but the Royals were hitting, too. In fact, Willie Aikens celebrated his 26th birthday by homering — not once, but twice — off winning pitcher Bob Walk.

“It could have been better if we won the game,” Aikens said. “I was just glad to go out and do well, and have it be on my birthday.”

Aikens first homer gave the Royals a 4-0 lead. His second — ”…I kind of guessed on the pitch. I was looking for a fastball inside, and it was there” — pulled the Royals to within 7-6 in the eighth inning.

That’s when the Phillies went with the left-hander. Enter Tug McGraw. Exit Kansas City.

“I don’t have enough brains to know if I’m in trouble or not,” McGraw said, making little note of the fact that he entered the game with one out and the Royals threatening to take command.

McGraw saved not only the Phillies, but Walk as well. A rookie, Walk’s opening assignment was no gem. Besides Aikens’ two homers, he allowed Amos Otis to hit one as well.

After the Royals had taken a 4-0 lead, Clint Hurdle singled with two out and Darrell Porter on second base.

Porter rounded third and headed for the plate. In left field, Philadelphia’s Lonnie Smith fielded the ball and threw it toward the plate. The race wasn’t even close. “He was out from here to the coaches’ office,” Schmidt said.

At the time it seemed insignificant.

“Everybody figured we could hit him (Walk),” Otis said. “He was throwing the ball all over the place. He was high, he was low. He was all over.

“If we’d kept it 4-0 through the sixth or seventh, I don’t think they could have come back on us.”

Game 2

PHILADELPHIA — If there is one reason the Philadelphia Phillies were in the World Series, it is because of Mike Schmidt. All season long. when the Phillies were down — almost out — Mike Schmidt came through with the big hit.

A double here. A home run there. When it counted, when it really mattered, Mike Schmidt came through.

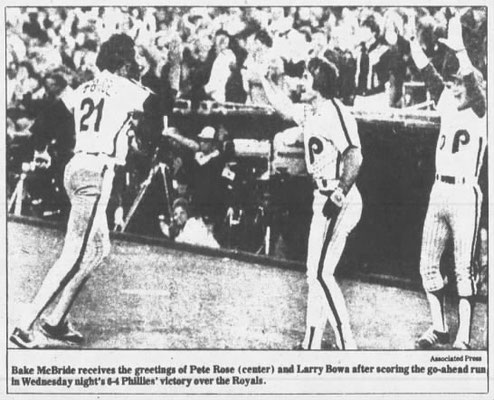

Eighth inning, second game of the World Series. The Phillies had come from behind and tied the Royals 4-4. Philadelphia base-runner Bake McBride edged away from first base; Schmidt waited at the plate.

“Nobody had any doubt we were gonna scare them to death,” Schmidt said after the game. "We knew there would be some people running around the bases before it was over.”

The Phillies did more than that. They won 6-4, and guess who had the game-winning hit?

Schmidt hit a drive off the fence in right-center field and McBride circled the bases. Schmidt scored an insurance run on Keith Moreland’s single.

It was another come-from-behind victory, the Phillies’ second in the World Series.

“That’s been Philly baseball all season,” Philadelphia Manager Dallas Green said.

It wasn’t Royals baseball. After all, Dan Quisenberry was the pitcher when all this was going on. If you believe in statistics – and isn’t that the very foundation of baseball? — Quisenberry was baseball’s top relief pitcher. He figured in 45 regular-season victories for the Royals, including 33 saves. When Larry Gura tired in the sixth inning, there was no question who Royals Manager Jim Frey was going to bring in to take care of the Phillies.

This time it was the other way around, though. The Phillies took care of Quisenberry.

“He’s been the guy that’s been doing it all year,” Frey said. “We had the right man out there; it just didn’t work out.”

The Phillies’ starting pitcher was the guy who had been doing it all year in the National League. However, Steve Carlton, 24-7 and a cinch for his third Cy Young Award, didn’t do it against the Royals.

“This is a great team we’re facing,” Schmidt said. “We know they’re not going to quit. They’ve come back each game, too.”

In eight innings, Carlton allowed 10 hits and six walks. The Royals constantly seemed to have a rally in progress. Even so, the Phillies led 2-1 after six innings, but then the Royals broke through. On only one hit — Amos Otis’ 2-run double — three Kansas City baserunners crossed the plate.

Although the Royals were missing George Brett, who had taken himself out of the game in the sixth because of a severe hemorrhoidal condition, and Willie Wilson still hadn’t got a hit in the World Series, things looked good for Kansas City. If the Royals ever were going to have Steve Carlton — and the Phillies — in trouble, this was it. Except the Phillies weren’t paying attention.

“When Boonie (catcher Bob Boone) went up tp lead off the eighth inning,” Moreland said, “we were all screaming and hollering… The whole dugout just seemed to explode. It came alive just like it has been doing for some time now.”

Boone walked; Del Unser doubled and the Phillies were on their way.

“Confidence,” Schmidt said. “It’s just a feeling of confidence we ll get the job done.”

Attitude, effort, superstition make up Frey’s magic formula

KANSAS CITY (AP) – Jim Frey has worn the same shoes and sweat shirt for more than two weeks.

Until his Kansas City Royals lost Tuesday in the first game of the World Series in Philadelphia, Frey had steadfastly refused to take out the lineup cards at game time. First base coach Jose Martinez had been on a winning streak.

He always sits in the same spot in a stadium, except at Philadelphia, where, as his club had never played there before, he didn't have a spot.

Among the many things that make up Jim Frey, the Royals' rookie manager, is superstition.

“Jose Martinez and I alternate with the lineup card,” Frey said. "If he loses, I go out. If I lose, he goes out. I always keep the card in the same spot. I sign my name the same way, and I try to use the same pen, but the boys steal it and foul me up sometimes.”

Sometimes pugnacious or vindictive toward men with silly questions, Frey has been a model of propriety in his club's first World Series. He reached the pinnacle of a lifelong dream of managing in the major leagues when he guided the Royals to the American League pennant over the New York Yankees, and he believes that fundamentals and a good altitude helped get him there.

Frey was hired to manage the Royals after the end of the 1979 season. He was with the Baltimore Orioles, who were involved in a World Series of their own, when he first was contacted.

“I wasn’t contacted by the Kansas City ball club until the third game of the World Series in Pittsburgh,” Frey said. "That morning, I got a call at 9 a.m. I met with them at noon, and I was told I was one of those considered for the job.

“I had read stories in the paper, but I hadn't been contacted before that.”

Frey had labored as a minor league outfielder for 14 years, then went to work for the Orioles in 1965 as a minor league manager. In 1970, he joined the Baltimore staff, first as hitting instructor, then as bullpen coach and finally as first base coach for the four years prior to joining Kansas City.

"I never honestly believed I would manage,” Frey said. "I thought I would coach and coach and coach and be fired one day. I was never encouraged by anyone. I was offered a job managing in Triple A, but I thought to coach in the majors was better than managing in the minors .”

Frey, 49, was born and raised in Cleveland but now lives in Timonium, Md., with his wife, Joan. They have three daughters and a son.

Frey attended Ohio State for two years, where, of course, he played baseball.

"I still plan to graduate some day," he said. "I just haven’t gotten to it yet. I went to school for two years I took a year off to make some money, and I never came back.

“I was invited by the Braves to come up and work out for two weeks in the fall of '49. I went home for one week, and then I signed," Frey said.

He never regretted his decision.

"At a young age, I decided I’d like to stay in baseball," he said. "Obviously, since I played 14 years in the minors, I had hoped I could stay in the game after I was done playing.”

Now, he said, he still can’t quite understand why the Royals came to him.

“But I never asked," he said "and I'm not going to.”

Ken Brett out of spotlight, stuck in George’s shadow

By The Associated Press

Ken Brett's face is beginning to show the creases of his travels. He feels and acts baseball-old. After all, he was on a major league roster at age 18, pitched twice in the World Series when he was 19, set a major league record for pitchers by homering in four consecutive games when he was 24, and won the All-Star Game for the National League at 25.

Now he is ancient and washed up, and knows it. He is 31.

He looks across the clubhouse at his baby brother, George, who has always been almost as handsome, charming, talented and blessed in the barroom virtues as he. But not quite.

“I was always a better hitter than George. Still am," said Ken.

He isn't joking. All the battling Bretts knew that Ken had the best chance to make it in baseball. He was the gifted one.

"I had the good tailing fastball and a sharp slider," said Ken, who won 13 games In three separate seasons, but never got over the hump to greatness. He now has a mediocre career record of 82-84.

“I pitched all the hitters the same way. I dictated to them. That is, I did when I was going good. I never developed a good, big breaking ball.”

Or a good change-up Or a knack for varying speeds. Or…

A week ago, Ken Brett, who had five shutout innings in his first three relief outings as a Royal, faced Cleveland with two men on base. He walked the first batter to load the bases, then hit the next to force in a run. He got the quick hook.

Later, he sat in front of his locker — over which he had pasted a baseball bubble gum card of his hero, George Brett — and said, "I appreciate everything about baseball a lot more now. I was in the World Series one month after my 19th birthday. I didn’t even know where I was. If we could make it to the Series this year, and I could work a couple of innings and George could hit one… wouldn’t that be something?"

Ken Brett, the brother with the looks and the talent, the man who has been with 10 big league teams, gave a quiet smile. His flame has finally switched to low pilot. He has learned to face facts.

“People think I’m here to have a mature influence on George,” he said. "George doesn't need me. He's been grown up for a long time.

"If anything," said Ken, "I just hope I'm not a hindrance to him."

From their origin as “Kansas City’s Baseball Club’ to their run at reality, Royals have been successful

How the Royals became the best expansion team

By Gib Twyman, A Member of the Sports Staff

On June 11, 1968, the American League awarded an expansion baseball franchise to Ewing M Kauffman. Four days later, he hired Cedric Tallis as general manager. Four days after that, Cedric hired secretary Peggy Matthews.

This constituted the Royals’ empire.

“We moved into some Chamber of Commerce office space in the Hotel Continental,” recalled Ms. Matthews, now executive secretary to Vice President-General Manager Joe Burke. “It had been an office used by Ernie Mehl (former sports editor for The Star).

“I had no desk,” Ms. Matthews said. “So Cedric and I sat facing each other on either side of his desk with a phone between us.

“We didn’t have any paper, no pencils, nothing. I remember Charlie Hughes (member of the Royals’ board of directors and then vice president of Marion Laboratories) brought over a cardboard carton with some Marion memo pads, pens — one stapler, some glue and a roll of Scotch tape.

"The next day, they put a phone for me in a room next to Cedric’s. But there was no desk and no chair, so I sat on the floor, me and this cardboard box, answering the phone.

“Cedric, the cardboard box and me — that was the Kansas City Royals.

“Actually, we didn't have a name yet. We had some stationery made, but it just said, ‘Kansas City Baseball Club.' And for weeks that’s how we sent out our correspondence.”

The beginnings strike a familiar chord. In much the same manner, Ewing Kauffman started selling pharmaceutical products out of the basement of his home. That grew to become the multi-million-dollar empire, Marion Laboratories.

The Royals didn't wait for official trappings, either. No fancy kickoff. They just dug in and began working.

The other guys worked hard, too, but the Royals worked harder. Today they stand as the most successful expansion franchise in baseball history. At age 12, they dosed out the 1980 season with their fourth Western Division championship. Then they swept the New York Yankee from their path for their first American League pennant in 25 years of professional baseball in Kansas City.

The Royals have a cumulative 1020-917 record (not including World Series games). They are the only one of 10 teams added to the major leagues since 1961 with a winning percentage — .526.

They profited from Kauffman’s open-checkbook policy in their formative years. And from his knack of hiring the right people at the right time. Tallis, Lou Gorman, Joe Burke, John Schuerholz — each has been peculiarly suited to guide the Royals to the top.

The night was June 21, 1968. A skinny, blond 21-year-oid pitcher from Morningside College in Iowa walked to the mound at Bowman Field in Williamsport, Pa., hard by the base of the Bald Eagle Mountains.

He was the season-opening starter for the Corning, N.Y., team in the New York-Penn League. He drew back his left arm and fired a fastball for a strike past the Williamsport leadoff man.

The pitcher's name was Paul Splittorff.

He was the first pitcher to start a game in the employ of the Kansas City Royals.

That was interesting — since, technically, there were no Kansas City Royals. They had not yet played an inning in the American League. Aa far aa the league was concerned, they did not officially exist.

“I remember they announced that I would be the starter in the first game for their first minor league team and I wasn’t even signed yet,’’ Splittorff said. “I signed June 20 at the next night I was pitching for them.”

It would be four months before the Oct. 15 draft that stocked four expansion teams in the major leagues — Kansas City and the Seattle Pilots in the American League, the Montreal Expos and San Diego Padres in the National.

It would be 10 months before Kansas City’s American League debut, a 4-3 victory over the Minnesota Twins on April 7, 1969, at Municipal Stadium.

But the Royals rushed a farm team into operation.

“We got a jump on the other teams from the very first,” said Tallis, now vice president of the New York Yankees. “Mr. Kauffman gave us the go-ahead to start rounding up players. He committed $400,000 to the operation the summer before the expansion draft.

"That enabled us to push our way into the June 1968 free-agent draft. Seattle didn’t want to participate, but we insisted.

“Commissioner (William) Eckert said, 'You can’t be in the free-agent draft. You’re not even in business yet.’ We told him, ‘The heck you say. We’ve spent a quarter of a million dollars already for players and a minor league operation. All we want to do is get the pipeline in place and start filling it.’

“That convinced the commissioner. All that debating earned us the right to get the 84th player available. We at enter the draft until it reached the Class A level. That means that after ail the 10 existing teams drafted players on the major league level, the Triple-A level and the Double-A level, the expansion teams got level to join in.

“Though we led the fight to get in, when we drew lots, we up fourth among the new teams.”

With that 84th pick, the Royals made Kenny O'Donnell, a shortstop from Monmouth, N.J., their No. 1 choice.

Their No. 22 choice was Paul Splittorff. Overall, he was the 482nd man chosen.

Splittorff has just completed his 10th season with the team. He has won more game than any other pitcher in Rovals’ history, with a record of 137-117. In 1973, he became the club’s first 20-game winner with a 20-11 record.

The Splittorff case is a testament to the Royals' uniqueness. They beat the other teams to the punch. Visionary, hungry, the Royals’ organization from the very first knew the direction it would take.

And it got the men to take them there.

If there were such a thing as a John Wesley Hardin Award for highway robbery in baseball trades, they could bronze Cedric Tallis’ face for the statue. Bold, with the heart and nerve of a riverboat gambler, Tallis was a charger. From 1968 to 1972 be had a Blockbuster-a-Year trade streak that was the marvel of his rivals. From other clubs Tallis spirited away Lou Piniella, Amos Otis, Cookie Rojas, John Mayberry and Hal McRae. Often, the opposing general manager was left still wondering what shell the pea was under.

Lou Gorman's touch in the draft was just as Midas-like. George Brett, Willie Wilson, Steve Busby, Clint Hurdle, Dennis Leonard, Rich Gale, John Wathan and Paul Splitthorff sprang from the draft in Gorman’s tenure. Frank White and Washington were products of Kauffman’s brainchild, the Baseball Academy. But Gorman and Tallis made the personnel decisions that put White and Washington into the Academy. In addition, Dan Quisenberry was picked up as a free agent during the Gorman years.

Eight men regularly in the Royals’ 1980 starting lineup were procured during the Tallis-Gorman era – Brett, McRae, Washington, While, Otis, Wilson, Hurdle and Wathan. Of the pitchers, Leonard, Splittorff, Gale, Quisenberry and Marty Pattin were collected by Tallis and Gorman.

But the Royals have had a happy habit of wedding the best person to their organization at the best possible time. And where Tallis was the perfect general manager to plant the Royals’ seeds, Joe Burke was the perfect one to bring them to fruition.

The Royals never won a title until Burke came. Not as spectacular as his predecessor, Burke made his mark with a firm but gentle hand.

A man who didn’t require a massaged ego, Burke saw no reason to paint a mustache on a Mona Lisa. The Royals were good and Burke knew it. He didn’t turn things topsy-turvy just to leave his imprint.

He made telling additions. Burke hired Whitey Herzog as manager halfway through the 1975 season. The Royals finished 41-35 under the popular, able Herzog and won the next three West Division championships. When the Royals faltered in 1979, Burke fired Whitey amid a fusillade of adverse public opinion and hired the unheralded Jim Frey. Picked for third in most quarters this season, the Royals ran away with the division. Frey is a leading candidate to be manager of the year.

Burke's trading instincts are more conservative, but three of his deals rival Tallis' for steals: the acquisitions of Larry Gura, Darrell Porter and Willie Aikens.

And even though some of the young talent, like Wilson, Washington, Hurdle, Gale and Quisenberry, were in the organization when Burke came, it took good handling to bring them along properly. Burke had a deft touch.

When Gorman left in 1976 to take over as general manager of the Seattle Mariners expansion team, his replacement was John Schuerholz. The Royals' farm system has remained one of the most vibrant in baseball under Schuerholz.

First Lieutenant Cedric R. Tallis, L Company, 4th Infantry, clung to a dump of rocks. It was raining, as usual, in the Battle of Attu, a chunk of mud and stone on the westernmost end of the Aleutian Islands. The Allies had 20,000 troops trying to root out 2,600 Japanese, squirreled away in mountains.

“They were courageous men and they wouldn't give up," Tallis said of the Japanese. "The battle lasted two weeks and when it was over we took only 14 prisoners.”

One night Lieutenant Tallis gave the command for the 53 men under his command in the Third Platoon to move forward. That's when a 25-caliber bullet from an Arisaka rifle creased his skull.

"I was lucky," Tallis said. "It put two holes m my helmet, two in my helmet liner and wool cap. It hit me in the front of my helmet, spun it around and put a crease right over my ear. It also scared the living heck out of me."

Tallis hears “crickets" to this day — "a high buzz that seems common to that kind of wound." He came away from World War II a major, with a purple heart and a bronze star.

Compared to Attu, living dangerously in the major league baseball trading market was nothing. It became the trademark of the Tallis years in Kansas City.

"We had to gamble in the early days," said Tallis. "It’s easier to gamble when you re down — you don't have to worn about upsetting your team too much. We could have waited for the farm system to produce it all. But the Chiefs were very much dominant in town at that time. I felt we needed to do something to make an impact.”

The ink was scarcely dry on the contracts of the 30 players taken in the Oct 15, 1968 expansion draft before Tallis engineered his first trade.

On Dec 12, 1968, he sent 45-year-old knuckleball pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm, the 25th man drafted, to the California Angels. In exchange, the Royals got catcher-outfielder Ed (Spanky) Kirkpatrick and catcher Dennis Paepke.

"We thought a relief pitcher would not be that great an asset our first year since we were unlikely to have many leads to preserve. Anyhow, we were desperate for catching,” Tallis said.

Wilhelm had a 5-7 record for the Angels. He creaked along for three more years with four teams before retiring.

Kirkpatrick became one of the more popular early Royals and gave them five strong, versatile years of service in the outfield and behind the plate.

Tallis next turned his attention to a special purchase of minor league players allowed to the expansion teams at the end of the 1968 season.

“The main idea was to get some borderline players, mostly veterans, to fill out our minor league rosters,” said Tallis. "This way we wouldn't have to rush any prospects along simply to fill a position at a given level.”

In Tallis’ hands, borderline people also meant trade bait. John Gelnar, a left-handed pitcher, was one of those "roster fillers." And he was a key to Tallis’ first spectacular. On April 1, 1969, just before the Royals broke camp In Sarasota, Fla., Tallis made a deal with his expansion sister, the Seattle Pilots. The Royals had taken Steve Whitaker, an outfielder supposedly with power-hitting promise, in the expansion draft. Whitaker and Gelnar were sent packing to Seattle for a hot-blooded Latin outfielder who was a refugee from the Baltimore and Washington organizations.

That outfielder was Lou Piniella.

“We happened to know Seattle had too many right-handers," Tallis said. “And we also used a little psychology. We gave them 2-for-1 because we wanted them to feel they were getting the upper hand.

“Piniella hit a home run for us his first at-bat in a Royals' uniform in an exhibition game against the Cardinals," said Tallis. “Then he went on to get four straight hits opening day."

Those four hits sent Piniella on his way to the American League Rookie-of -the-Year award. He hit .282, then .301 the next season. He hit ,312 in 1972 and made the All-Star team He finished his five years as a Royal with a .288 cumulative average.

Whitaker hit .250 for Seattle and .111 the next year for San Francisco before disappearing from the majors. Gelnar, over the next three years, posted 3-10, 4-3 and 0-0 records for the Pilots, who became the Milwaukee Brewers.

On Dec. 3, I960, Tallis made the trade that gained him a place in the New York Mets’ Hall of Infamy. The Mets got third baseman Joe Foy, the Royals' No. 2 pick in the expansion draft. The Royals got Amos Otis and Bob Johnson.

In a strange twist one man present at the bargaining table for the Mets in one of baseball's great giveaways was Whitey Herzog, then the Mets' player personnel director.

"Whitey was not in favor of trading Otis," Tallis said. "It was Gil Hodges (then the Mets' manager). He didn’t like Otis at all. They had tried to make a third baseman out of him and Amos didn’t like fielding those hard ground balls.

“When it got down to it, Johnny Murphy (Mets' general manager), Hodges and Herzog were on the other side of the table. We wanted Otis badly, but we also wanted to squeak Johnson into the deal. Finally, I got up to leave and said, ‘Well gentlemen, there is no way we can make this deal if you don’t include Johnson.'

"My heart was in my throat because I thought I'd blown it. Forty-five seconds went by with nobody saying a word. Finally, Murphy blurted out, ‘Oh, what the heck, OK. I'll Just have to check it with Mr. Grant (Donald M Grant, owner of the Mets)’ He did and the deal was made."

Otis became one of the American League’s premier center fielders, named to the All-Star team in 1970, '71, '72, '73 and ’76. In 11 seasons with Kansas City, he has a .280 average. Johnson had an 8-13 record for Kansas City and struck out 206 batters. Foy joined the long revolving-door procession of Mets third basemen. He hit .236 in 1969. He was traded the next year to the Washington Senators where he hit .234 and dropped out of the majors.

Having secured center field, Tallis further strengthened the Royals down the middle with a deal for Cookie Rojas. Kansas City got him from the Cardinals for outfielder Fred Rico. Rico had been purchased for $25,000 and hit .231 in six games for Kansas City in 1969.

But Gorman knew the Cards liked Rico. "Rico played for Omaha (the Royals' triple-A American Association affiliate), and every time they played Tulsa (the Cardinals' farm team) Rico tore them up," Gorman said. "I knew Spahnie (Warren Spahn, the Tulsa manager) loved Rico. And Rojas was doing nothing but sitting on the Cardinals’ bench."

Cedric swung the deal with Bing Devine, the Cardinals' general manager. Rico never got another time at bat in the major leagues. Rojas hit .300 in 1971, his first full year with the Royals. He became the linchpin of the Royals' infield for the next seven years and was named to the American League All-Star team in 1971, ’72, ‘73 and ’74.

Next, Tallis went looking for a shortstop to cement the middle. The man he got was Fred Patek, and the lure Tallis used to catch him was Johnson, the second man obtained in the Foy fiasco.

On Dec 2, 1970, Tallis sent Johnson, shortstop Jack Hernandez and catcher Jimmy Campanis to the Pirates in exchange for Patek, catcher Jerry May and pitcher Bruce Dal Canton.

"Actually,'' said Tallis, “I didn't want to give up Johnson. I wanted to trade Jim Rooker. But Danny Murtaugh (Pirate manager), just looked up at me with those eyes of his. Sort of like a beagle's, big and round and protuberant. We had to make it Johnson.”

It didn't matter. The Tallis luck held. Patek became a darling of the Kansas City fans. For eight years, he and Baltimore’s Mark Belanger were considered the best-fielding shortstops in the American League. Patek was an All-Star in 1976, '77 and ’78.

May stuck three years with Kansas City, starting intermittently. Dal Canton had a 25-27 record in five years in Kansas City.

Johnson known as much for flakiness as for his fastball, had a 9-10 record his first year as a Pirate. Then he foundered, going 4-4, 4-2, 3-4 and 0-1.

Campanis hit .167 in six games with Pittsburgh. Hernandez hit .206 in 1971, though he fielded well and was the starting Pirate shortstop in the 1971 World Series. But Hernandez hit .188 and .247 his next two years before leaving the majors.

Exactly one year later — on Dec 2, 1971 — Tallis Lightning struck again. He sent reliever Jim York and pitcher Lance Clemons to the Houston Astros for John Mayberry. Clemons was noteworthy because he had played on the Royals’ 1968 Coming, N.Y., team as a power hitting first baseman. He was the only man besides Splittorff to reach the majors from the club's first farm team. While he never made it with the Royals, he helped them get the best power hitter in their history.

“I had happened to be in Omaha when I saw Mayberry hit home runs over three different fences for Oklahoma City. Our scouts gave him excellent reports,” Tallis said.

“We never thought we had a chance for him until Houston made a trade with Cincinnati for Lee May. That meant Big John was out of the Astros’ picture at first base.

"We set up shop literally on (Houston general manager) Spec Richardson’s doorstep. He had a cabana at the Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix and it just so happened we had one right next to his.

“The Astros were frantic for relief pitching. And in York, they were getting in my opinion, the best young right-handed reliever in the American League. He had had a tremendous year for us the year before.”

Mayberry hit 25 homers and drove in 100 runs in 1972, his first year as a Royal. The next year he had 26 and 100. He peaked at 34 homers and 106 RBls in 1975. In five of his six years with Kansas City, he had 22 or more home runs.

York, on the other hand, had one thing in common with Sandy Koufax. Blisters. He was plagued by the same kind of circulatory problems that short-circuited the Dodger ace’s brilliant career. York went 0-1 with the Astros his first year. He won 9 and lost 10 for them over the next three before departing from the majors. Clemons had an 0-1 record for St Louis and 1-0 for Boston in 1974. That was it for his major league career.

For the third straight year (1972), Tallis dropped a bomb on Dec. 2. He again demonstrated his talent for unloading players when their market value was highest. Tallis traded away Richie Scheinblum, a .300 hitter, and Roger Nelson, the Royals’ Pitcher of the Year in 1971. Nelson had an 11-6 record and set Kansas City records for shutouts (6) and earned run average (2.06) that still stand.

Still, Tallis traded him… and got the better of it. Nelson and Scheinblum went lo Cincinnati for Hal McRae and Wayne Simpson. In the first year it was known as the Nothing-for-Nothing Trade because all four principals struggled. McRae was the only one to come out of it. After stumbling in his first year, he hit .310, .306, .332, .298, .273, .288 and .297 his next seven years. He became the Royals' second best hitter, next to George Brett.

Nelson battled arm trouble that had begun to surface a the end of the ‘72 season. He went 3-2, 4-4 and 0-0 his next three years, tumbling out of the majors in 1977.

“The deal was concluded on the last day of the winter meetings in Honolulu,” said Gorman. “Cedric and I were about to give up, but I said, ‘Look let’s go up and give it one more shot with the Reds.’ We went to Howsam’s (Bob Howsam, the Reds’ general manager) room. Sparky Anderson (Cincy manager) and Larry Shepard (the Reds' pitching coach) were there too. We talked for three hours. Somebody would go off on a tangent about some other subject. Cedric and I would always gently bring the conversation back to McRae.

“We kept harping on the fact that he was just sitting on the Reds’ bench. They said, ‘Well, we’re giving up a good hitter, we’ve got to have some flitting in return.’ That ’s when Scheinblum went into the deal.”

Scheinblum hit .222 for Cincinnati. He hit .328 for California in 77 in games in 1974, but the next year dipped to .191. He then returned to Kansas City, where he hit .181 and left the majors.

“We burned the midnight oil,” said Tallis. ”We worked hard. We tried to hire the best scouts because they are the key to any trades and drafts.

”We ran a ’we’ type of operation. I couldn’t do any of this by myself.

“There’s no question the deals we made couldn’t be made as easily today because of the restrictions. All the fret agent rules and special contract considerations make it extremely difficult now.

“Things just seemed to happen for us. The little chinks of the jigsaw puzzles always fell into place for us. We were able to offer something to somebody at just the time they thought they needed it.

“And let’s face it. We were lucky, too. Darned lucky.”

In the summer of 1972, Municipal Stadium was saying farewell. After 18 years as the home of Kansas City professional baseball, it was giving way to the new Royals Stadium, to be opened on April 10, 1973.

One of the ushers during that last year at Municipal Stadium was a man named Jim Washington. He told anyone who would listen that he had a brother “who can play this game” back in his hometown of Stringtown, Okla.

One man who listened was Lou Gorman.

“It was U.L. Washington’s brother that led us to him,” said Gorman. “Finally I told him we’d take a look at U.L .at a tryout camp for the Baseball Academy.

“Jim sent the money for U.L.’s bus fare to the tryout camp in Municipal Stadium. We had 360 men that day. U.L. was one we kept.”

Not before a lot of debate. Schuerholz singled U.L. out at the tryout. Soon a crowd of team officials gathered — all watching U.L.

"He showed outstanding speed and outstanding arm," said Gorman. “But he was a bad-looking infielder. He just couldn’t handle ground balls at all. He couldn't hit either.

“But John (Schuerholz) and I liked him. We gave U.L. the usual battery of tests — hand-eye coordination, balance, psychological. He didn't fare well on them.

"But he was exceptional in speed, strength and eyesight. And the fantastic thing about him was his makeup — his willingness to go out and work hard, day in, day out.

“In one year at the Academy, his progress was amazing. He fielded ground balls by the thousands and spent hours on the batting machines. Finally, we took him to Class A ball at Kingsport and from there he came the regular minor league route.”

Washington is the Royals’ regular shortstop today. Along with second baseman Frank White, he is one of the great success stories of the academy. A tribute to Kauffman's idea, Gorman’s sympathetic ear, the scouts’ sharp eyes — and the persistence of a brother.

Persistence and luck paid the biggest dividend in Royals’ history in the 1971 June free-agent draft — the acquisition of George Brett.

“There was a catcher out of Midwest City High in Oklahoma City that everybody in baseball agreed was the best prospect in the draft. And we needed a catcher badly,” said Gorman.

“We drafted sixth, though. And Milwaukee drafted second. So they took the catcher. His name was Darrell Porter.

"The second man on our list was Roy Branch, a pitcher out of Beaumont High in Houston. He had copied every mannerism of Bob Gibson, and just about pitched like him, too. He had a 90-mile-an-hour fastball and his curve ball was phenomenal.

“The third man on our list was George Brett. He was a shortstop out of El Segundo High School in California. There were a couple reasons we listed George third. He played short all his high school career and he didn’t really look like a shortstop, so you had to project him at another position. He handled the bat beautifully, but he wasn’t phenomenal as he later became.

“We agonized all night at the Americana Hotel in New York the night before the draft. John Schuerholz, Gary Blaylock, Tom Ferrick, Al Diez, Herk Robinson and myself.

“All of a sudden Dale McReynolds, our midwest scouting supervisor, calls us and tells us Branch has hurt his arm in a tryout the day before with the Cardinals. We called the Cardinals and George Silvey, their farm director, told us, no, as far as they could see Branch was all right.

“Now we were really mixed up. We went round the table and the vote was split. We did it again and split again. Ferrick said, ‘If Branch isn’t OK, Brett would be a heck of a No. 1.' But we decided to take a chance on Branch. I thought if he was healthy, he might be the outstanding right-hander in the league for years to come. He was the best pitching prospect I had ever seen.

“Well you can imagine how shocked we were when Brett was still available in the second round. We held our breath and got him, too.”

Branch's arm trouble was real and he never made it. But Brett's ability was for real too. Picking him was only half the battle, though.

Signing Brett was a challenge and Kauffman met it. “Ewing was very instrumental in the signing of George. He was able to guarantee George some aspects of his contract," said Tallis.

“In lieu of cash, he gave George the opportunity to purchase Marion stock. The key factor was that Ewing guaranteed George against any depreciation in the stock.”

Gorman said, "Our whole philosophy from the start was to build from within. A belief in good scouts was the key for us all. You need to organize them properly, then interpolate their judgment. We just did our homework and pounded away.”

Gorman was hired in February of 1968 from Baltimore, where he learned the Build-From-Within manifesto. He was graduated with honors from the Oriole organization. In the last draft he directed for them — 1968 — Baltimore got Bobby Grich No. 1 and Don Baylor No. 2.

‘I’ and ‘my' are words used

By those who have themselves confused

Why won ’t their superegos trust

The use of words like 'we’ and 'us?'

That poem was composed by John Schuerhoiz “after I just finished taking a man to the airport who said nothing but 'I' and 'my' the whole trip.”

The sentiment is at the heart of the Royals’ personality.

"We are a ‘we’ organization,” said Schuerhoiz, “and always have been. The ‘I’ people do not stay around very long. The ‘we' people usually remain.

“They fit in, they contribute. Not in a yes-man, condescending way. They have the strength to stand alone. But for each of them the most important thing about the Royals is the Royals.

“There’s no way a man can mastermind the job of player procurement by himself. I fancy myself as a conductor holding a baton before an orchestra playing a beautiful piece of music. My job is to take the voices of the many scouts — men whose egos may sometimes tend to thrive on the people they sign — and get them to harmonize.

“I don't consider myself a super evaluator of talent, though a very adequate one. But I can write symphonies. Sometimes when we’re not playing together, I have to tap my baton quite loudly on the podium.

“From Day One, our efforts were designed to mold the Kansas City Royals along the lines of a specific type of player. These would be men with speed, who could play defense and had good character — very important — the kind who would be a winning-type, team player.

“Cedric Tallis, Mr. Kauffman, Charlie Metro (the first director of scouts), Lou Gorman, myself. We discussed the type of player we wanted many times. And there was never a man among us who disagreed.

“We took that philosophy to our scouts. We told them exactly what we wanted to do and they began doing it from the very first.

“We purposely set out to mold a different kind of ballplayer — a new breed a Kansas City Royal, something that had never been before. We have never wavered more than 1 or 2 degrees from that original philosophy."

If ever a player personified the speed-defense-character Royal, it's Willie Wilson. Chances are, only an organization as thorough as the Royals could have signed the man who led the American League in hits and runs this season.

In the spring of 1974, Wilson was stamped for college football and just waiting for delivery. He was an All-America running back at Summit, N.J., High School, picked in the same backfield as Earl Campbell. More than 250 colleges drooled at his doorstep and Coach Jerry Claiborne of prize when Willie signed a national letter of intent.

Said Schuerholz, "It was only because of a super, super scouting job by Al Diez that we signed Willie. Al, himself, was a fascinating study in what makes a scout tick. Here was a man who was working for the YMCA in Minneapolis. He wanted to get into baseball. He left his family in Minnesota and took up residence on Long Island, N.Y. — on a part-time experimental basis, yet.

"He moved into a motel in foreign territory in a sea of competitive scouts and proceeded to establish himself. Al had only lived on Long Island one year before he took on the challenge of Willie.

“Several baseball teams had Willie in for tryouts,” said Schuerholz. "Everybody in the game agreed he was going to play football. But Al became familiar enough with the family to tell us, ‘If you draft him you can sign him.’ Thirteen teams ahead of us passed him up and we got him.”

Schuerholz was a 26-year-old English literature and world geography teacher at North Point Junior High School in Baltimore when he got into baseball.

One day in study hall, instead of grading papers, he wrote to the Baltimore Orioles, saying he would like a job.

"I expected a reply saying, ‘Thank you very much for your interest, blah-blah-blah.’ But I hit it lucky. Unbeknownst to me, Lee MacPhail had just gone to the American League office, Harry Dalton became the Orioles’ general manager arid Lou Gorman became the farm director. That left an opening for assistant farm director.

I had an hour-and-a-half interview with Gorman. Six weeks later he offered me the job. I was three feet off the ground — and have been ever since.

"The greatest thing Lou ever did for me was let me try my wings and fail. I fell to earth a lot and got back up again. But like Jonathan Livingston Seagull, I learned to fly.”

As far as I am concerned,” said Joe Burke, “I have made my last move in baseball. I hope to stay with the Kansas City Royals the rest of my career.

“I don't believe in the old baseball adage that you’re hired to be fired. I don’t fear for my job. If you feel insecure, you wall make so many mistakes you will get fired. I have worked for three organizations — the Louisville Colonels (American Association), the Washington-Texas club and the Royals.

“And I’ve been very fortunate that in 32 years in the business I've never been fired.”

Burke will probably be able to stay with Kansas City as long as he wishes. The reason is that Joe Burke is an immensely capable administrator. He has never enjoyed the public fanfare that more flamboyant general managers exult in. But it doesn’t bother him.

“If you were to query the other 25 clubs and ask them who is the best organization in baseball,” said John Schuerholz, “you would find 20 of them would list us in the top 5

“If you asked them who is the most astute operator of a major league baseball franchise today, Joe Burke would wind up 1, 2 or 3. He is ready a talented man."

Burke endeared himself to Kauffman by straightening out the Royals' finances when he came to the team as Vice President for business on Sept. 3, 1973.

Joe has endeared himself less to the public since he became General Manager on June 11, 1974. Too conservative, the critics say, in the big-time free-agent market.

“If I have to give them the stadium, the club and half of Marion Laboratories to get them, I don’t believe we should,” Burke said. “It’s not in the best interests of the team.”

Burke has been perceived as slow on the draw in the trade department, too. In reality, he has been highly successful.

“I don’t believe in trades just to change uniforms," Burke said. “These players have wives, kids in school. Too often we think changing the scenery will make a difference.

"You trade to fill a hole, not to revamp a lineup. I don t know of anybody who has been smart enough to rip up a whole club end come out ahead.

“I’m a strong believer in chemistry. I feel it's better to have 75 percent talent and the right chemistry than 100 percent with the wrong blend.

“You can get a player with 110 percent ability with 60 percent desire and when you need him, he's not there.

‘‘You can look up and down the major leagues and see teams who have thought they bought a pennant, but they didn't have the chemistry and nothing happened.”

Burke made two sweetheart trades in 1976. On May 16, he sent starting catcher Fran Healy to the Yankees for pitcher Larry Gura. Healy is now a Yankee broadcaster. Gura has been second in the league in games won by a left-hander over the last four years. He is 55-32 in a Royal uniform. He pitched the opening victory in this year 's American League Championship Series.

On Dec 6, Burke traded Jamie Quirk, Jim Wohlford and Bob McClure to toe Brewers for Darrell Porter and Jim Colborn.

Porter made the Ail-Star team in 1978 and ’79, peaking last year at .291, 20 homers and 112 RB1 before tailing off this season. Coiborn threw a no-hitter and was 18-14 for Kansas City in 1977 before plunging to 1-2 and finishing his career with Seattle in '78. Wohlford has been a part-time player for Milwaukee. McClure has had 2-1, 2-6, 5-2 and 5-3 records the last four years. But he has been an effective reliever. Quirk has since been re-purchased by the Royals.

"Being Joe Burke and conservative, I don't like to gamble much,” he said. "The reports on Darrell were horrible. He wasn’t catching well, had a lot of passed bails and be couldn’t hit a lick. The year before we got him he hit .206.

"But we thought if he got a chance to develop, we'd have a great catcher. We knew he had personal problems, so this was one case we thought changing scenery might work. My risks, maybe, are percentagewise in my favor. I like to look into them a lot before I taka a chance. We felt 75 to 25 percent the deal for Darrell was in our favor."

Last Dec. 6, Burke traded Al Cowens and Todd Cruz to the Angels for Willie Aikens and Renee Mulliniks.

Aikens hit .278 with 20 homers and 98 RRIs. He drove in the deciding runs in Game 1 of the series against the Yankees. Cowens, since traded to Detroit, hit .268 with six homers and 57 RBIs.

"This was just a case of taking the one commodity we had, outfielders, and looking for a power hitter. We felt Al had peaked for our club, though maybe not with another one," Burke said.

Burke's ability to evaluate personnel also was demonstrated in the Nov. 5, 1976 expansion draft that stocked the Seattle Mariners and Toronto Blue Jays.

Burke had to let one of three players go — Willie Wilson, U.L. Washington or Ruppert Jones. Since Washington was the organization’s only heir-apparent to Patek at short, the choice came down to Wilson or Jones. Both were cream -of-the -crop prospects — outstanding speed and defense. Jones had more power.

"We knew when we let Ruppert go he would be the No 1 choice in the draft and the best player in it. But we decided Willie was going to be better for the long haul,” Burke said.

When Jones led Seattle with 24 homers the next season and Wilson hit .253 for the Royals' AA farm team at Jacksonville, some people thought Burke was daft. But Wilson’s performances the last two years have proved the decision correct.

"Player development and instruction from top to bottom have always been the heart of the Royals’ approach," said Burke. “We are probably in the top 5 percent of teams for homegrown players. I feel over the coming years a strong farm system is going to be even more important. With free agents able to leave clubs after six years, you need a farm system to replace them. I believe the teams who have cut back are foolish.

"We have been very fortunate to have an owner with the resources and the patience. If we had an owner who wanted to make a lot of changes, I don’t believe we would be as successful.”

The first thing you must do is associate yourself with — I don't want to say ‘hire' — capable people to come and work with you,” said Ewing Kauffman.

"Second, you must give them the authority and responsibility to do their jobs. Give them their head.”

Kauffman put himself out front when he replaced Bob Lemon with Jack McKeon as manager for the 1973 season. And Ewing joined the hunt for the only free-agent trophies the Royals ever pursued to the hilt — Catfish Hunter, Tommy John and Pete Rose. None of them came through.

Other than those instances, Kauffman basically has followed a hands-off policy.

“Any major trade — by that I mean a Brett or McRae or White — the general manager will discuss it with me. It affects PR (public relations) and I want to know about that," Kauffman said.

"But generally speaking, Joe has been in baseball all his life and I haven’t. My goodness, I ought to trust his judgment.

“Now, an owner I didn’t necessarily respect was Charlie Finley. But he knew baseball players. And he was successful making trades. Maybe I could learn that much if I took enough time away from Marion Labs. But I can’t afford to do so.

"So I leave it to Joe. And I would have to say I am leaving it in the most capable hands in baseball.

“Just one example — at the first of last year, Whitey and all the coaches wanted to send Willie Wilson down (to the minors). They said he wasn’t ready. Joe Burke said, ‘Absolutely not.’ He wouldn’t stand for it. Well, we all saw what happened.

”I think we were successful because from the very start we believed in player development. We had 23 full time scouts, more than anybody else, by 1970. We had 50 summertime scouts. Where most teams went with four minor league teams, we operated six. That gave us an extra 60 players to look at.

“We’ve got to give an enormous amount of credit to the fans of Kansas City. Our season-ticket sales were a little over 12,000 this year and next year we're looking at over 14,000. We have decided we must place an absolute ceiling at 15,000 because of the problems it creates for the playoffs."

In his own view, Kauffman has a succinct answer to what has set him apart as an owner. "Probably a willingness to spend money to train players,” he said. After taxes, Kauffman figures he has lost $9.6 million in the Royals’ 12 years.

Would he do it again?

“When I was losing a million dollars a year in cold hard cash the first six years, I did not think so. I thought the money could have been put to some better use in the community.

"As of today, though, yes I would.”

Fan creates a record to sing Royals’ praises

By Gib Twyman, A Member of the Sports Staff

It has been a season for singing the Royals’ praises. Larry Stewart has taken that literally — so far to the tune of $9,000.

That is what Stewart has spent to finance a record about the Royals’ rise to the World Series. Stewart, owner of a cable TV marketing firm from Independence, calls it “The Baseball Polka.’’

The 4S-RPM record features Larry Stewart as the writer.

It features Larry Stewart as the producer.

It features Larry Stewart as the singer.

‘‘I just sorta financed and basically did the whole deal myself," Stewart said, walking off the plane with a Royals' hat on his head at Philadelphia International Airport before Game 1 of the Series at Veterans Stadium.

Why did he do it?

"I’m just a fan,” Stewart said “I go to about a third of the games. The Royals are great. They’re tremendous. I wanted to do something special for the special season they’ve given us.

"One night a bunch of us were sitting at the ballpark hearing them play the ‘Beer Barrel Polka,' like they always do and I started thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be fun to put some words to that about the Royals.’”

Stewart was so certain the Royals would make the World Series that he began pouring money into his project two months ago.

"I had about $2,500 in production costs," said Stewart. “I recorded it at Sound Recorders, Inc., in Kansas City at 3947 State Line. Then I spent about $3,500 pressing the records at United Record Pressing in Memphis. I had about three trips to Nashville and Memphis — about $1,400 — to line everything up.”

The flip side of the record says, Stewart, is “about a guy named George with No. 5 on his back.

“My 5-year-old son, Joey, gave me the idea for that. We were driving along one day and he said, ‘You know who my hero is?’ I said. ‘No,’ expecting him to say what any 5-year-old would say — his dad. But he said, ‘George.’ I said, ‘George who’?’ I wasn't even thinking about baseball. He said, ‘Brett.’ So I decided to write it for him."

The song has been played on 61-Country (WDAF) and KMBZ. Stewart initially had 10,000 records made. He says approximately 3,200 have been sold.

"If there are any proceeds they will go to the George Brett Scholarship Fund at Kansas City, Kansas, Community College. Ron Mears is my friend. He's the guy who dreamed up the ‘George Brett for President' bumper stickers. That money goes to the scholarship fund, too.”

And the lyrics to this little ditty?

Here are a few:

“Throw out the baseball,

The color for this year is blue.

I’ve got the Series fever

And I'm a fan like you.

Oh we got it,

We got it,

This time we're gonna win

It doesn't really matter

What town we 're playing in

Throw out the baseball,

Our guys are ready to play,

With smiles on their faces,

This time it's all the way.

Seeing Royals in the Series is compensation for fans who cheered in lean years

Taylor T. Harvey said that if he had to, he would crawl to Royals Stadium this weekend.

"You couldn’t keep me away,” said Harvey, a 78-year-old commercial realtor. Harvey is one of several long-suffering fans who have owned season tickets during the 13 seasons the Athletics were in town and the 12 years the Royals have been here.

It’s a rare Kansas Citian who isn’t excited about the Royals World Series in Kansas City, but those die-hard fans who paid for season tickets during the lean years — as well as during recent seasons of relative prosperity — might enjoy the games a little more than others. They can take pride in having waited it out.

Harvey thinks winning the World Series would be the greatest thing that could happen in Kansas City. Of course, just being in the series is pretty good, too.

“I think it's terrific,” Harvey exclaimed in his office in North Kansas City.

Harvey still goes to his real estate office every day, and he and his wife, Leiah, attend most of the Royals’ home games. From their front-row seats near the visitors' on-deck circle, the Harveys have made friends with many players, including Reggie Jackson of the Yankees and Jim Sundberg of the Texas Rangers.

Harvey, a Platte County resident, said that over the years he has accumulated about 70 baseballs autographed by various players.

Some of Harvey's friends from the old days include Charles O. Finley, former owner of the A’s; Luis Aparacio, former infielder for the Chicago White Sox; and the late Nellie Fox, also a White Sox infielder.

Harvey said he has never forced himself onto players, but that they have sought him out. Doubtless, the players who have befriended Harvey appreciate a true fan, just as Harvey appreciates the players' efforts on the field.

Another longtime season ticket holder who’ll be riding high when the Royals take the field tonight is Sam Gould, parking lot mogul. Gould, who is 63, operated as many as 15 parking lots in the vicinity of 22nd and Brooklyn when the A’s, and later the Royals, played in old Municipal Stadium.

Gould now owns two downtown parking garages and a few lots. At the stadium, he and his wife, Lucy, sit in the fourth row behind the visitors' dugout.

Gould said his biggest thrill was the arrival of major league baseball in Kansas City in 1955. But having the World Series in Kansas City ranks very close behind.

“It’s still kind of hard to believe,” said Gould. “It will be hard to believe until we see them out there.”

Gould has been involved with baseball in Kansas City for a long time. When he was about 10 years old he began working in the clubhouse of the Kansas City Blues, and later he worked at the old stadium in concessions and as an usher.

He bought his first parking lot in 1950.

"I was more of a baseball fan than a parking man when I started,” he said.

And that’s exactly what he’ll be this weekend, a fan.

Sarah Schere, a 25-year season ticket holder, will be at the stadium in spirit, but not in person. Mrs. Schere is the owner of the Lone Eagle Auto Parts Co. at 19th and Oak.

She and her husband, Hyman Schere, attended many games until Schere's death 10 years ago. Mrs. Schere retained the tickets, but a few months after his death she was badly burned in a kitchen accident. Since then, Mrs. Schere has not been as active as she had been, and this week she has been suffering from a cold.

Instead of going to the weekend games herself Mrs. Schere will let family members use her front-row seats behind the Royals' on-deck circle.

But her absence from the stadium has not diminished her excitement.

“I think it’s absolutely wonderful,” she said. "I am just thrilled…. And honey, we’re winning the Series. So don't worry about it. We are going to take first place.”

NBC’s World Series director works on mark that might be unbeatable

On the Air By Steve Nicely