Philadelphia Inquirer Playoff Special - October 7, 1980

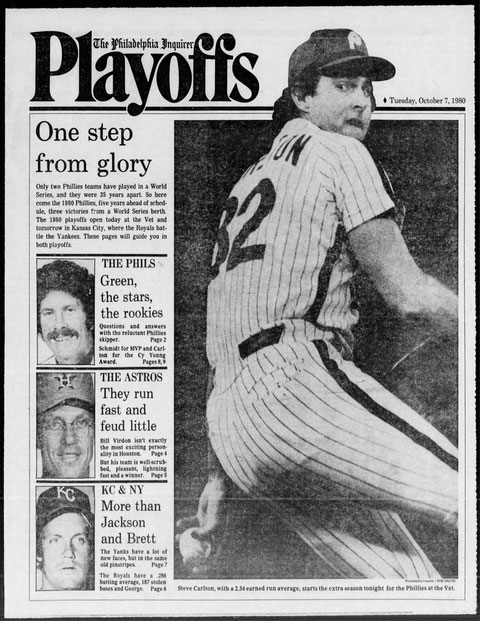

Managing turns off Green as he turns thoughts to future

He never really wanted the job, but when he was finally convinced to lake it, he decided to do things his way and i the players didn't like it, they'd have to fight him every inch of the way.

And, at times it was a tough fight. He took over from "nice guy" Danny Ozark and replaced that image with a regime that one player termed "Gestapo," but the critics can't argue with the results.

Dallas Green might have hurt a few feelings and stepped on a few egos, but he has pushed the Phillies up a hill they fell from last season. However, should he finally whip them over that hill, he doesn't really want to be the man pushing them again next season.

Question. Obviously, at the beginning of the season you thought the Phillies could win the division, but were there ever times during the season when you thought that maybe you were wrong? Was there any time you thought the team was out of it?

Answer. A lot of guys sold us down the river after the Pittsburgh fiasco. I still felt deep down that if we could ever get our act together we could win it. I didn't know at that particular time if we could do it, but we were six down (with 55 to go) and that shows you something about us.

Q. How much do you feel responsible? How about your different strokes-for-different folks approach to your players?

A. I think the end results speak for themselves. I think now there are more people in our locker room who understand what I am trying to do with this team than they did in April or even July.... I think there are a lot of guys who are tired of fighting me. I might get caught a few times, but I'm certainly going to get my licks in.

Q. You were never too thrilled with the idea of managing to begin with. Has the race for the divisional championship and the winning of it made the job any more enjoyable?

A. I have never not enjoyed winning, from a player to a job in the organization, so that part of it, the winning, has been enjoyable. But the managing part... enjoyable? Uh, that's an adjective I don't think I could use with managing.

Q. So, why do you do it? Why put up with a job you don't enjoy?

A. There are a lot of people doing jobs they don't enjoy. I happen to be a baseball man. And I believe in what this organization is trying to be a winner. 1 happened to believe I was the best man for the job at the time. I respect Paul Owens and when he asked me to do the job I accepted.

Q. Then you don't expect you'll go on as so many guys do, managing different teams?.

A. I've got no aspirations to be a career manager. It's just a part of my career that will fall into place later on. Managing was the furthest thing from my mind a couple of years ago.

Q. Then you don't expect to be managing in a few years?

A. I'm going to struggle with next year.

Q. Are you saying you might not be coming back next season?

A. If we, or I should say when we, win it, there won't be a helluva lot more to accomplish, will there?

Q. Then, if the team wins the World Series you won't be coming back?

A. I would prefer to do that. I haven't talked to anybody about it yet. But if we do win it I would prefer not to be in uniform next season. If I don't stay... I would prefer to have a hand in saying who would take over the team, however.

Q. What would be your feelings if the team does not reach the World Series?

A. I wouldn't feel that we accomplished what we set out to accomplish. It's something to say you've won your division four out of five years, not many can say that. But, like I said, nothing would be accomplished until we get into the World Series. And I'm sure there are a lot of individuals on the team who feel the same way.

Q. Has winning the division, at least, in any way made all the aggravation of the season worthwhile?

A. Yeah, when you win it kind of eases the pains of all the frustrations. It wasn't until the night we clinched the division that I sat back and thought about the month of September. I don't think too many teams went through what we went through in September. Talk about playing with your backs to the wall. Our backs were against the wall almost the entire month of September. We had to win almost every time we went out there and we banged out one of the best Septembers we've ever had.

Q. Do you see any signs that your methods are working, that things are changing with the team?

A. I think so. Wino (Coach Bobby Wine) knows. He's been around here a long time and he says he's seen the team show more intensity toward winning than it ever has before. That gives me personal satisfaction. And I don't think I've ever seen a Phillies' bench as excited as ours when we won the division in Montreal.

Q. Do you think that your position in the organization, 25 years here and very secure, has made any difference in the way you manage?

A. I never thought about it, but maybe it has. The fact that I'm fairly secure might have something to do with it. These guys know I'm not going to get fired. With other managers, maybe they feel he's going to get fired.

Q. What about the team in the future? There are some players who have been here awhile and now there are some younger players pushing for jobs. What do you see for the future?

A. Well, win, lose or draw we've got to take a look at the situation. That doesn't mean I'm suggesting wholesale changes or any changes at all. We've just got to take a look at it. We've got to look toward the future a bit and try to fill in a few holes we might have. If the guys we have aren't good enough to win it, I don't know how long we can wait for them.

Q. What about the future for you? You don't want to manage, what direction do you think your career will take you?

A. Well, since I don't have enough money to own a team... I think, basically, I'm trained to end up a general manager.

Now look at the Phils, ye nonbelievers; and this time they insist on the Series

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

The million and one days in a baseball season mostly blend together. But there is always the one day, the day you never forget. It bounces around your memory. It won't go away.

For the 1980 Phillies, Aug. 10 in Pittsburgh was the day.

It was the day Dallas Green stormed into the locker room, pointed his finger and screamed the word "quit."

It was the day they lost both ends of a double-header to the Pirates, their third and fourth losses of the weekend, and plopped six games behind Pittsburgh and Montreal.

It was the day they knew they couldn't get any lower or play any worse.

It is not so much the games that day that stick in the memory. It is the feel of that locker room, the quiet that spoke volumes, the lone voice of Pete Rose, speaking of what must come next.

"I think the best thing for us now," said Rose that day, "is to get United Airlines to get us up over those clouds and get us to Chicago. I don't care if we lose three in a row in Chicago. The best thing for us now is to just get out of this town and let somebody else come in here."

United Airlines did its job. It got the Phillies out of Pittsburgh. And somehow, when they came back down beneath those clouds, they found themselves again.

The tight, shell-shocked team that got battered by the Pirates was never seen again. They won two of three in Chicago, five of five in New York and they were rolling. They were 36-19 from that day on. Exactly 20 days later, they moved into first place, and they were never more than two games out of it again.

"That weekend in New York just did something to us as a ballclub," said John Vukovich, a reserve infielder but perhaps the keenest observer of Phillies affairs. "There we were, at our lowest point going into Chicago. And we won two of three, with the best-pitched game from (Dick) Ruthven the only one we lost. Then we swept the Mets. We'd won seven of eight on the road. We'd picked up some ground. And we said, 'Hey, wait a minute, it ain't too late.'"

So just at the point when their town gave up on them, they began roaring in the other direction.

They beat the Giants in a draining 13-inning game, the night Warren Brusstar had the bases loaded in the 11th and nobody out. They came home and mugged the Pirates twice in their final at-bat. Then New York, and the coming of Marty (0.00) Bystrom. And then a deal for Albert (Sparky) Lyle. And another extra-inning win over the Pirates.

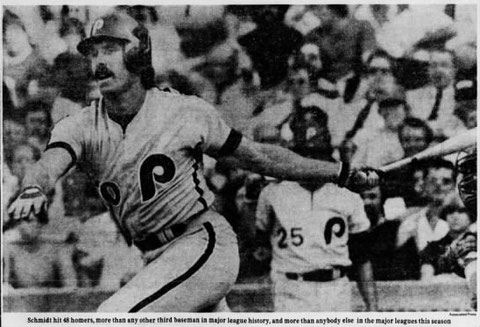

And then the final week, with three-eighths of The Nucleus on the bench. And Green in his office, questioning whether some people on his clubhouse really wanted to win. And two runs down to the Cubs in the 15th and not folding. And finally, Mike Schmidt pumping No. 48 into the lower deck in Montreal in the 11th inning Saturday.

And so this team had won its fourth National League Fast title in five years. But winning this one felt different from the others.

"It means more to me," said Schmidt, "because there were times during the season when people gave up on us. And yet we came back and won it. We made believers of a lot of people.

"Plus we had to battle to win it. We had more problems. We had to have more intensity throughout the year.... We'd never really been in a pennant race. We never had to play great baseball in September. The other years we won it, all we had to do was just hold on."

This year, they went 23-10 from Sept. 1 until the Saturday they clinched it. And they couldn't have afforded to be a single win worse. They went 12-3 in one-run games. They went 5-0 in extra-inning games.

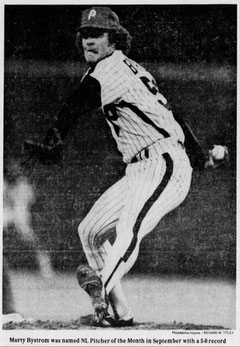

They no longer won by outslugging everybody. They won the grind-it-out way. They got pitching, and not just from the September MVPs, Bystrom (5-0, 1.50) and Tug McGraw (5-0, 0.33. five saves). The whole staff's ERA from Sept. 1 to Clinch Day was 2.67.

And the offense finally made the adjustments it had to make, from "Thunder Road" to the "E Street Shuffle." They bunted, moved guys over, hit behind runners, lofted sacrifice flies. And those 13 Schmidt homers were just gravy.

"I said back in spring training I wanted to change some things on this ballclub," said Green. "In particular, I was concerned about the character of this team.

"I wanted to try and stay away from just winning games on ability because I felt the rest of the National League had caught up to us in ability. I felt we had to stay close to the team concept and work hard to build the character of this team. And I think it was that character that really pulled us through in September."

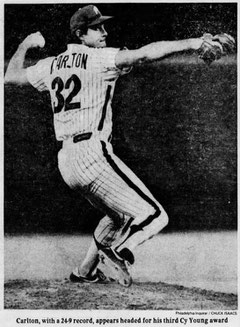

It wasn't just character that won them this division, though. Steve Carlton winning 24, allowing one earned run or fewer in 16 starts, that sure didn't hurt.

"He never let us get hurt too badly," said Green. "That's one of the reasons we are where we are right now. Even put him down for 17 or 18 wins, which would be a damn decent year for anybody, and we're in trouble."

And Mike Schmidt had his best and most consistent year – 48 homers, only three when they were more than three runs up or three down, 28 tying games or putting them ahead – and batting .286 besides.

And without Bake McBride knocking in 87 runs on one leg, it would never have been possible, either. McBride didn't start 30 games, but he still totaled a remarkable 144 runs produced. And he was so steady that after April, he never hit lower than.284 for any month.

And finally, there was McGraw, who went from his worst year in 79 (4-3, 5.14) to his best (5-4, 1.47). After the All-Star break, McGraw was scored upon in only three of 33 appearances, beat the Pirates and Expos twice each and saved 13 of the 16 games in which he had save opportunities.

It always helps to have four guys having the season of their lives. But other things helped, too. In a strange way, Greg Luzinski's knee injury in July was one of them. Because Lonnie Smith came along, and they found out he could play.

"Even when Bull came back, it was like the first time this ballclub ever had a nice problem," said Vukovich. "In the past it's been 'These Eight' and that was it. If we lost one of those eight, we were in trouble. This time we had a guy who kept us in the race."

There was Keith Moreland, who hit.412 as a pinch-hitter and came out a winner in 22 of the 32 games he started. And Bob Walk, who was 8-1 on Aug. 1.

And Bystrom, who came so far so fast he would have pitched in the one-game playoff with the Expos if there had been one. And Larry Christenson, who returned from the operating room to compile a 2.77 ERA in eight starts over the last two months.

"I think long before LC ever took the mound, there was a feeling that, 'Hey, this guy is going to come back and help us at a time when we needed to stay close,' " said Vukovich.

All of those things happened from within. But another factor you can't discount was the importance of the collapse of that other Pennsylvania team. When the volume of that Pirates stereo started to fade in the distance, it removed the final stumbling block in the Phillies' psyches.

"I think this ballclub, from the beginning of spring training, was overly concerned about the Pirates," Vukovich said. "People said they had the whammy on us, and I think there was some validity to that. When they went into that bad slump, it boosted our confidence. It made us feel like, " 'Hell, we can still come through and win this thing.'"

They have done that now. But they have done nothing more than three other Phillies teams did. And for all of those teams, October was the cruelest month.

Green has said that this time, he wants to win a playoff and get to the World Series "or I'll feel as if we haven't accomplished a damn thing." For once, he has his players' complete agreement.

"I think we all realize," said Bob Boone, "that without a World Series, this is going to be an empty winter."

Virdon: That other ‘coach’ in Houston

By Hal Lundgren, Special to the Inquirer

Houston – Bill Virdon could be the most popular man in Houston.

If only his Astros would win all 162 of their games.

Instead, they have settled for prevailing in more than 90 games, enough to win their first National League West championship.

Virdon is the "other" half of the Houston coaching phenomenon. Folks love Bum Phillips, the Oilers' coach. They brag over the way he's taken cement-truck drivers, Softball players, ice-cream vendors and city firemen (plus a few Earl Campbells and Ken Stablers) and molded them into a team that has gone 29-14 the last 2½ years.

Five of the 14 losses were to Pittsburgh, they plead.

Then there's Virdon, who has less wit, less charm and clearly less public support.

Local talk shows on a nightly basis hear from a caller or two who blasts Virdon for leaving a pitcher in too long or failing to go to the correct pinch hitter.

Letters to a newspaper's weekly sports forum are divided 50-50 on Virdon. Many of the anti-Virdons insist the Astros would have clinched the NL West championship a lot sooner than yesterday's playoff game with the Los Angeles Dodgers had their field leadership been stronger. Any day now, they might start calling him Danny Ozark of the West.

Houston newspeople are almost undivided on the manager. They think he's a magician who has taken a team that has a talent shortfall and finished in front of Los Angeles and Cincinnati.

Virdon, his ego unaltered by fans who would like to see him disposed, prefers to ignore the negative reaction.

"I don't know of anybody who likes that type of thing," the skipper said with tongue in cheek. "I wish we could win every day. But no matter how hard you try not to let any games get away, some of them do."

Three of them did last weekend in a crucial series with the Dodgers and it almost cost Virdon and the Astros the division title.

"It was a great series," said Virdon of the games his club lost 3-2, 2-1 and 4-3. "We just didn't win any. In the key situations, they got the hit and we didn't."

Until yesterday. But even going into that decisive game, Virdon heard from the critics again – the ones who suggested he had let his team get down on themselves, that he had permitted a dropoff in intensity and, perhaps, even effort.

"There hasn't been any change in mood, desire or effort," Virdon said before the one-game playoff. "We have to win now. We haven't had to, not that we haven't tried."

The fans may have been a little quicker to criticize Virdon this year, recalling that in 1979, the Astros – who have never won a championship of any kind in their 19-year existence – faltered badly in the season's second half after leading the West Division by as much as 10 games in June.

"This team is more mature," he said, mentioning the additions of flame-thrower Nolan Ryan and two-time Most Valuable Player Joe Morgan. "This is a lot better club.”

Getting people to believe it has been the problem.

They haven't taken us seriously this year or last. We probably have as much speed as anybody in baseball. We're a little deeper in pitching than most people give us credit for, even without J.R.Richard."

But still the criticism persists. "When a game does get away, there are always people who think they could have done better. That's normal. Most fans have grown up around base ball and have probably played it. And all of us like to think we have a little bit of smarts."

As a baseball manager, Virdon sees himself an easier target for the second-guesses of fandom.

"Baseball is spread out on a large field and the basics of the game are obvious to fans," he said.

"In football, the players are grouped closer together and things happen at once. It's easier to criticize baseball."

"I don't resent the criticism. I understand it. The only thing that upsets me is when the critics are supposedly intelligent people who run their own businesses. I don't understand how those people can complain when they're not on the scene and couldn't be aware of what's going on with all 25 players.

"I'm not saying they shouldn't criticize because I don't make the right moves all the time. I'm still learning, and I've been in this business 30 years.

"What I'm saying is that there are always little things that affect decisions. You have to be on the scene to know about the little things."

If people overlook the little things, nobody misses the big ones. Virdon is managing one of the most inoffensive contenders in many seasons.

Baseballs don't carry well in the Astrodome. If they did, Houston's hitters wouldn't serve many to the bleacher customers. Terry Puhl tops his club with 13 home runs. Kids from Taiwan have been known to strike that many balls out of the park in a single Little League World Series.

Houston's defense, at best, is fair. Third baseman Enos Cabell was the worst in the league until he pulled out of a fielding slump at mid-season. Cesar Cedeno isn't far behind Garry Maddox as a centerfielder. But Jose Cruz in left and either Puhl or Danny Walling in right aren't much better than average.

Second baseman Joe Morgan and shortstop Rafael Landestoy and Craig Reynolds all have range limitations. When Reynolds starts, he's usually a greater batting liability than the pitcher.

Still, Virdon wins.

"People make a big thing about our power," he said.

"We've hit nine more home runs than our opponents this year. That's an advantage for us. It doesn't matter how many home runs our opponents have against other teams. It's only the ones against us that should matter."

Asked before last weekend which team he'd like to meet in the NL playoffs, Virdon backed down, claiming, "When and if we win our division, we'll focus on the team we'll play."

He did concede that Montreal catcher Gary Carter could be murder on Houston base-running. (Seven Astros will finish the season with 20 or more steals.)

"Carter could counter our running game," Virdon said.

He also was not thrilled about the possibility of seeing Steve Carlton a few times in a short series – something that may happen if the series goes beyond three games.

"Any team that had to face Carlton twice in a playoff series would have trouble. We realize... that we'll have to beat a good team to eel to the World Series."

He does have a preferred opponent in the World Series. New York. And not, he says, because he was fired by the Yankees before they hired Billy Martin. "It would be good for our club and good for our city if we played New York," he said. "It would make the World Series more of an experience.

"The franchise has been here 19 years. Attendance this year was two million. The people and the city deserve anything we can give them."

Astros: a collection of straight shooters

By Ed Fowler, Special to The Inquirer

If the incident was going to involve any one of the Astros, it was going to involve Joaquin Andujar, resident flake and practicing moon child. The wonder was that even he among Bill Virdon's well-scrubbed legion deviated a step from the straight and narrow.

Andujar did it with a flourish, however. Not content to get himself alone thumbed off a PSA commercial flight at the gate of the San Francisco airport two weeks before the season ended, he managed to get teammates Jose Cruz and Julio Gonzalez, whose crime was being seated on the same row, tossed off with him. The dispute arose over Andujar's refusal to stow his tape player under his seat on the plane, and by the time he repented and agreed to do as the stewardess asked, the plane, which had begun taxiing, was under tow back to the gate.

The captain, brooking no nonsense, went aft and cleaned out the entire row, manager Virdon's mannerly protestations carrying as much weight as they would with an umpire.

It was a flukish turn of events for the National League West Division-champion Houston club. The Astros have their foibles, but by and large they line up in public behind the stern Missouri countenance of their manager, and no one breaks step. A private, gentlemanly fellow who last raised his voice when the doctor raised him by his ankles and slapped him on the bottom, Virdon will have it no other way.

He allows his players no alcohol on flights, chartered or commercial. "The only times I've been embarrassed by being in baseball, as a player, coach or manager," Virdon says, "involved players with time on their hands and the availability of alcohol. If any of them say anything to me about the rule, I tell 'em if they can't go without a drink for two or three hours I'll get them a psychiatrist, because they need help."

Unlike some of his peers, Virdon requires his players to take infield practice before each game and forbids beards and long sideburns. "I can't really tell them not to and make it stick," he says, "but I tell them I'd rather they didn't have facial hair, except mustaches. If a guy has a mustache he generally keeps it short and neat. A big part of our job is selling the public, and there's no need to give the public something to object to. As long as you're going good anything goes, but if you go into a slump some people will start looking for things to get on you about."

Virdon imposes his sanctions with little resistance from the players, in large part because the club has been constructed with more than a casual eye to character. Catcher Alan Ashby is a Mormon, shortstop Craig Reynolds a devout Baptist who, with his roommate, outfielder Terry Puhl, organizes chapel services each Sunday the Astros spend on the road. The character factor goes beyond church attendance, too.

If the 1980 Astros were told to behave like the all-conquering Oakland A's of the early 70s or the world champion Yankees of two seasons ago, they would be at a loss. There are few clubhouse fights, deprecating remarks about teammates or foes (the J.R. Richard incident being one notable exception), altercations with fans. The Astros, again mirroring Virdon, are courteous and straightforward, if not remarkably colorful, with the press. Only one player, Jeff Leonard, a brooding young man from Overbrook, refuses to talk for print. And he has played so sparingly, struggling to keep his average above .200, that hardly anyone has noticed.

Perhaps the Astros have been so restrained off the field to conserve their energies for their endeavors on it. They won their division with excellent pitching, good team speed, defense that is better than some but hardly inspired and power that is exceptional only when compared to last season's feeble production.

Virdon used more than 90 lineup combinations during the season in an effort to catalyze the attack. He finally settled on Joe Morgan, Enos Cabell, Cruz and Cesar Cedeno in the first four positions and stayed with that cast for the most part over the last two months, though he continued to shuffle his personnel down in the order. Against righthanded pitchers, too, he will sometimes insert Puhl in the No. 3 spot, dropping Cruz and Cedeno down a notch.

Predominantly a lefthanded-hitting club, Houston finished about 20 games above .500 against righthanders and did little better than break even against lefties. It played sub-.500 ball on the road.

The club has been tailored by general manager Tal Smith to the specifications of the Astrodome, with its distant fences and heavy air. Power has been sacrificed to speed and defensive acumen in every instance. The Astros had more than twice as many stolen bases as home runs. The spine of the defense is outfield speed. Cruz in left, Cedeno in center and Puhl all track down line drives with all but the top few outfielders in the league. There is not an exceptional arm among them, however; indeed, Leonard owns the only strong arm on the club and his is rarely showcased.

Neither are catchers Ashby and Luis Pujols gifted throwers. They shot down fewer than 25 percent of the base stealers who dared them.

The offense is centered on Cruz, the most consistent producer for the season and the club leader in RBIs and game-winning hits, and Cedeno, a five-time Gold Glove winner who has played with renewed panache since being restored to the outfield after spending most of the 79 season at first base. Benched for three games early in the year after leaving seven runners in scoring position in three games in Los Angeles, not once getting the ball out of the infield, Cedeno found new resolve and was a stalwart in the stretch run.

A disappointment over the years to Houston fans, who embraced him in the early 70s as "the next Willie Mays," etc., Cedeno at times this season flashed the form that can carry a club. "I think the pennant race helped him," said Virdon. "He reached back a little more."

Art Howe and Denny Walling, platooning at first base, both contributed offensively and played defense creditably for novices at the position. Third baseman Enos Cabell survived a mid-season fielding slump when he was troubled by a sore back, and shortstop Craig Reynolds shook off sub-.200 troubles at the plate to regain his position. Second baseman Joe Morgan also found his stroke over the second half and finished among the club's home-run leaders.

Gary Woods, who had been up with both Oakland and Toronto for a cup of coffee, was called up from the minors just in time to make him eligible for postseason play. Replacing Puhl in right field against some lefthanded pitchers, Woods drove in at least one run in eight of the first nine games he played.

The pride of the Astros is the pitching staff, which closed ranks after Richard suffered his stroke, in July and proved itself one of the league's best even without the overpowering righthander. Vern Ruhle, picked off the Detroit Tigers' slagheap, where he landed because of recurring shoulder problems in 1978, came back from back surgery in 79 and replaced Richard in the rotation. He was Houston's most effective starter in September. Knuckleballer Joe Niekro, a 21-game winner the year before, couldn't match that total but came close and led the club in victories.

The bullpen became perhaps the deepest in baseball with the emergence of righthanders Dave Smith and Frank LaCorte, who joined established lefty Joe Sambito. Those three earned a victory or a save in more than 60 percent of Houston's successes. Smith was a rookie who surprised everyone by making the club in spring training. LaCorte was, until this year, a scatter-armed veteran who was acquired during the 79 season in a little-noticed trade with Atlanta.

This cast was assembled by Smith, who became GM in August 1975, with an assist from John McMullen, principal owner since July 1979. A New York shipbuilder who was formerly a limited partner in the New York Yankees, McMulIen made it his personal project last winter to hire free-agent pitcher Nolan Ryan, and made him the highest-paid player in American team sports at $1,125 million a season for three years with an option on a fourth.

Smith, who had avoided the free-agent bazaar as though it were a war zone, watched from the sidelines as McMullen courted Ryan, then went shopping on his own. He signed Morgan, who he saw as the one player who could put the club over the top against the Dodgers and Reds this time out.

The owner and GM have had differences on matters other than talent evaluation. They held divergent views on National League adoption of the designated-hitter rule with the result that McMullen, who did not favor implementing the rule, ordered Smith to abstain in the voting at the summer meetings.

That may be a matter in passing, but if the differences between the men prove more profound the Astros, even as they are becoming a winner, may be a team in transition. "Tal is an excellent general manager," McMullen says, "and I don't have to go out to dinner with a man, I don't have to love him, to have him work for me. I think Tal is damned lucky to have the job he has, and I think he has a damned good boss."

Smith has one year remaining on his contract.

Royals didn’t win title by Brett alone

By John Morris, Special to The Inquirer

KANSAS CITY – Contrary to popular opinion, George Brett did not singlehandedly carry Kansas City to the American League West championship as part of his pursuit of the holy .400 average.

Brett, who will contend with Reggie Jackson, the Yankees' "Mr. October," for MVP, had a storybook season with a .390 average and 118 runs batted in in only 117 games.

But the Royals might have won what some critics call the American League Weak Divi sion without their All-Star third baseman. Kansas City made a runaway of the "race" in mid-summer and coasted to its fourth division title in five years, officially clinching it Sept. 17.

The Royals won the division by 14 games despite an eight-game losing streak in September, when the whole team settled back to let George do it.

First-year manager Jim Frey, a disciple of Earl Weaver, restored order to the Royal house by getting his team back to what it does best – hit and run.

While not blessed with a surfeit of power, Kansas City may be the best offensive team in the majors, with a .286 team batting average and 185 stolen bases in 227 attempts.

Willie Wilson, the young leftfielder, has become the most prolific leadoff man in baseball. The Summit, N.J., speedster was the Royals' top draft choice in 1974 but didn't move into the starting lineup until the 33d game of the 1979 season after Al Cowens got his jaw in the way of an Ed Farmer pitch. Wilson finished last year with .315 and 83 steals.

He has been even better this year, setting team, league and major league records in his first full season as a regular, batting .326, with 79 thefts in 89 tries. Wilson, who is also an excellent defensive player, became the first man in baseball history to bat 700 times in a season. He also set league records for consecutive steals (32), singles (184) and runs scored by a switch hitter (134). He also became the second player with at least 100 hits from each side of the plate (Garry Templeton of St. Louis was the first).

"Willie is our sparkplug. He ignites the rallies," says Darrell Porter, the Royals' All-Star catcher. "Willie definitely gives us an edge over other people."

Porter had an off-year after overcoming drug and alcohol problems early in the season. Porter hit only .249 with seven homers and 51 RBls and had defensive lapses.

Porter, who may try the free agent market this winter, could be replaced against lefthanders in the playoffs by John Wathan, who hit .305 while filling in for Porter and seeing occasional duty in the outfield and at first base.

Porter wasn't the only Royal regular to have an off-year. Centerfielder Amos Otis, who holds most of the team's career offensive records, batted only .251 with 10 homers and 53 RBls. He also led the team in interviews not given.

Veteran Hal McRae, the designated hitter, was reliable all season, finishing at .297, 14 homers and 83 RBls.

Willie Aikens, obtained from California in an off-season trade for Cowens, plays first like a man tied to a tree, but he did provide some power in the middle of the batting order with 20 homers and 98 RBls.

Rightfielder Clint Hurdle started to live up to his early promise, hitting .294, but Frey used veteran Jose Cardenal (.354) frequently in the late going.

U. L. Washington, who was given the shortstop job when malcontent Fred Patek played out his option, has covered a lot of ground and hit a surprising .273. Frank White (.264) is a Golden Glover at second.

Frey got good bench support from Wathan, Cardenal, Dave Chalk, Jamie Quirk and Pete LaCock. The Royals needed that help because the Big 4 of Brett, McRae, Otis and Porter combined to miss nearly a full season with injuries and illness. Brett alone missed 44 games.

The Royal regulars are healthy going into the playoffs, but some of the pitching arms are suspect.

Frey had picked Larry Gura, a noted Yankee-killer, to pitch the first game of the playoffs. But Gura hasn't been deadly lately. The lefthander is 18-10 with a 2.95 ERA, but he has been treated rudely in his last eight starts and hasn't won a game since Aug. 21. The Royals claim Gura's arm is sound but he has been ineffective since complaining of a "tired shoulder" in mid-August when he was 18-5 and had the best ERA in the league.

Gura isn't the only Royal with arm problems. Righthander Rich Gale has been sidelined with tendonitis the last six weeks and may not be healthy for the playoffs. Gale was 13-9 with a 3.79 ERA during the season, but he was throwing the best of his career before his injury.

That leaves righthander Dennis Leonard and lefty Paul Splittorff to start in Games 2 and 3. Leonard has been the Royals' best pitcher since the All-Star break (13-4) and finished at 20-11 with a 3.79 ERA. Splittorff, who has not been effective against the Yankees the last two years after dominating them for several seasons, is 14-11 and 4.15.

If Gale is unable to pitch and the Royals need a fourth starter, Frey may go to Renie Martin, a righty who was 9-10 with a 4.60 ERA as a long reliever and spot starter.

The AL playoffs will offer an interesting contrast between the two best relievers in the league – Yankee flamethrower Goose Gossage and Royal submariner Dan Quisenberry.

Quisenberry, who was tutored by Pittsburgh's Kent Tekulve during spring training, does an excellent imitation of the Pirate string-bean.

"Quiz" bailed out the Royal starters all season, finishing 12-7, with a team record 33 saves and a 3.10 ERA. He seems to be equally effective against right and left handers, but if Frey needs a southpaw out of the bullpen he may go to Brett.

Before you reach for the Hall of Fame ballot, that's Ken Brett, former Phillie resurrected by KC this summer. George's older brother spent a brief time with the Omaha Royals before moving into George's lakeside house in August. Ken has yet to give up an earned run in six relief appearances covering 13⅓ innings.

If the pitching holds up, the Royals are convinced they can reverse the outcome of their 1976, 77 and 78 playoffs with the Yanks.

That optimism is based on the makeup of the two teams. The Royals are quick to point out that Chris Chambliss, Mickey Rivers, Thurman Munson and Sparky Lyle were important factors in New York winning the earlier playoffs by 3-2, 3-2, and 3-1.

On the other hand, the Royals think this is the best of their playoff teams.

So, the positive thinkers in KC say, the Royals are stronger, the Yankees weaker and the results will be different.

The only problem with that formula is the fact the Yanks played their best ball in September while fending off Baltimore. The Royals looked entirely mortal the last month of the season after discouraging such pursuers as Oakland, Minnesota, Texas and California in May, June and July.

Off-season overhaul gave Yanks the flag

Special to The Inquirer

NEW YORK – The Yankees actually won this year's Eastern Division championship not long after they lost last year's.

In less than a month after the final game of the 1979 World Series, the Yankees acquired a new manager, a new general manager, a catcher, a center fielder, two righthanded hitters and two lefthanded pitchers.

The new manager was necessary because the old one, Billy Martin, was fired for punching a marshmallow salesman in a hotel in Blooming-ton, Minn. Martin's successor, Dick Howser, proceeded to manage the sometimes volatile Yankees in a low-key but effective manner.

The new general manager was Gene Michael, a former shortstop who was able to work with his former teammate, which was unlike Martin's relationships with previous front-office executives.

Rick Cerone was the catcher and he was perhaps the most vital acquisition because the Yankees desperately needed someone to replace the late Thurman Munson. Unsteady at first, Cerone blossomed into perhaps the best all-round catcher in the league, a development the Yankees had no reason to expect.

The centerfielder was Ruppert Jones, who was acquired from Seattle the same day that Cerone arrived from Toronto. That spot had been made vacant by the trade of Mickey Rivers to Texas last July.

In recent years the Yankees had played with an offensive attack that primarily included lefthanded hitters. After losing last year, they decided they needed additional righthanded punch so they signed Bob Watson as a free agent and obtained Eric Soderholm from Texas.

In dealing with Toronto for Cerone, the Yankees also picked up Tom Underwood, a left-handed pitcher, and secured another lefthander, Rudy May, in the free-agent market.

In other words, the Yankees were busy immediately after last seasons and it was by design.

Acting like a general in a war, George Steinbrenner, the principal owner, drew up his battle plans early and deployed his troops strategically. Then, as soon as the season was over, the Yankees blitzed the opposition, trading for players and signing free agents before other teams even thought of doing it.

Steinbrenner is that kind of operator, a consummate planner who might fire himself if he had found he had overlooked some minor detail.

Of course, the Yankee boss does not restrict himself to playing general. Among his other roles, he also plays psychiatrist. It was in that guise that Steinbrenner, in mid-August, unleashed a verbal barrage at his team, from the manager on down, and created the Yankees' biggest controversy of the season that otherwise was tame compared with some of their previous years.

At the time of Steinbrenner's outburst, the Yankees were struggling, having lost games and ground to the pestiferous Baltimore Orioles.

In the owner's diabolical thinking, he would so enrage his players that they would play harder just to show him he was wrong for berating them.

Whatever it was, Gen. Dr. Steinbrenner saw his troops start a streak about 10 days later in which they won 18 of 20 games and solidified their position in the race.

With Reggie Jackson enjoying one of the best first halves in his career, the Yankees dominated the division and steadily built their lead until it reached 9½ games in mid-July. Jackson, however, slumped early in August and so did the Yankees.

The Yankees, on the other hand, were afflicted with a series of disabling injuries of the kind that devastated other teams, such as the California Angels. Unlike the Angels, though, the Yankees had players sitting on their bench and playing in their minor league system who filled in admirably.

Two outfielders, Bobby Brown and Joe Lefebvre, especially helped the Yankees. Brown, who had drifted through the minors for eight seasons in five different organizations, was called upon for two lengthy periods during the season to replace Jones in center field. Brown played there for six weeks in the middle of the season when Jones was out following intestinal surgery, and he played center for the final six weeks of the season after Jones suffered a shoulder separation.

Aurelio Rodrigues played third base for most of the last two months of the season because Craig Netlles contracted hepatitis and was out of the lineup after July 23. Most people expected Nettles' absence to hurt the Yankees severely, but Rodrigues played defense like the outstanding defensive player he has always been, and he even added to his value by winning several games with hits.

The Yankees' second baseman, Willie Randolph, contributed many hits and walks that led to victories. He was the leadoff batter all season, and he developed into one of the best leadoff batters in the league.

Rich Gossage proved once again that he was the most awesome relief pitcher in the league. In 18 appearances from Aug. 9 through Sept. 21, he allowed not a run in 28⅔ innings. He registered 14 saves and one victory in that period and at one stretch retired 28 consecutive batters in seven games.

Among the starters, Tommy John was the most consistent pitcher throughout the season, surpassing the 20-victory plateau for the second time in his two seasons as a Yankee.

Like John, May joined the Yankees as a free agent and quickly became one of the most valuable members of the pitching staff. Alternating between starting and relieving, working wherever he was needed on that day, the lefthander pitched so effectively that some observers felt he had never pitched better.

The same couldn't be said for Ron Guidry, who had some problems. He went to the bull pen in August to try and straighten himself out and, when he re-emerged, seemed to have accomplished his goal.

Steinbrenner's goal in making the rapid round of acquisitions he did last November was to return the Yankees to the championship status they had enjoyed in 1976, 77 and 78. He succeeded, too.

The best arm, the biggest bat in the majors

By Frank Dolson, Inquirer Sports Editor

The National League's Cy Young Award winner?

"Steve Carlton's COT to win it this year," said ex-Phillie Jerry Martin after facing him last week as a member of the Chicago Cubs. "Hands down. Nobody's close."

The National League's most valuable player?

"Two weeks ago people were looking around," Tim McCarver was saying the day after the Phillies clinched the National League East. "But the last 10 days have been almost a different season. I mean Schmitty (Mike Schmidt) has sewed up the MVP."

Is Steve Carlton, at 35, the best pitcher in the National League?

Is AstroTurf green?

Has Mike Schmidt, at 31, finally matured into the most dynamic offensive machine in the league, as well as an often brilliant defensive third baseman? Is he, as McCarver said, a shoo-in for the most coveted award a major league baseball player can win?

Is Dallas Green's voice loud?

This is threatening to become the year of the Phillies – individually and collectively. They have the man who is almost universally considered the best starting pitcher in the game. They have the man who has harnessed perhaps the most awesome physical talents in the big leagues to become almost a classic MVP – a slugger who kept hitting the long ball down the stretch when his team needed it most.

It may be another couple of weeks before we find out if this is truly the year of the Phillies, but there cannot be the slightest doubt that 1980 will go down as the year that Steve Carlton and Mike Schmidt became, respectively, the dominant pitcher and slugger in all of baseball.

Carlton was simply phenomenal from day one, the "stopper" on a pitching staff that desperately needed one until all the pieces fell into place in the latter part of the season. It wasn't just his 24-9 record or his 2.34 earned run average or his 286 strikeouts in 304 innings. Above all, it was his amazing consistency.

The lefthander who will open the National League championship series for the Phillies tonight made 38 regular-season starts. In some of them he was great. In most of them he was good. In a few of them he was pretty good. Never was he bad. Never did he fail to pitch well enough to keep his team in the game. There can be no higher compliment paid to a starting pitcher.

How good is Carlton?

When his slider is diving across the plate, he's so good it's frightening. Like the Ron Guidry of 1978, he's virtually unhittable on his best nights and darn close to it on his average nights.

"If he doesn't go in the Hall of Fame, it's a fix," said Cubs manager Joey Amalfitano after watching Carlton two-hit his team in the final week of the season.

The way Carlton is pitching this year, they ought to build him his own annex to the Hall.

In 16 of his starts he yielded one earned run or less.

In 22 of his starts he yielded two earned runs or less.

In NONE of his starts did he fail to last at least six innings.

In 11 of his starts he struck out 10 or more batters.

In short, at an age when you'd expect a power pitcher to start going downhill, Carlton has been going up...up...up. His presence alone makes the Phillies a strong bet to win the National League playoffs and enter a World Series for the first time since 19S0.

"We used to talk about hint making a transformation from a power pitcher to a true pitcher," his pal, McCarver, said. "Now I think he's gone back to a good power pitcher because of his strikeout total this year. I think Lefty's run the full cycle.

"It takes awesome physical ability. Look at him and you fail to realize how physically intimidating he can be, and the way he keeps himself in condition. He's refused to allow his muscles to atrophy to the point where it (pitching all those innings) becomes a grind. Plus his hard mental makeup is of a caliber where he's unflappable – a picture of concentration on the mound."

Somehow, Carlton has found the perfect physical and mental mix to remain at the very top of his profession in this, his 16th big league season.

"True greatness really comes," said McCarver, "when you attain that fine mixture of physical intimidation and emotional stability."

It's the same mixture that Mike Schmidt found in 1980 after a long, hard search.

Call it maturity. Call it experience. Call it confidence. Whatever it is, Schmidt has it now. He's become the guy you want to see walking up to the plate with the game on the line, the guy most likely to deliver the big hit.

"He told me in spring training," said third base coach Lee Elia, "'I'm going to hit 45 (home runs) this year and when I hit the 45th I want you to give me the high sign.'"

A man of his word, Schmidt hit No. 45 against the Cubs' Dennis Lamp to break a scoreless tie Wednesday night.

Then he hit No. 46 against Randy Martz to tie the Cubs, 1-1, in the fourth inning on Thursday night. And he hit No. 47 against Scott Sanderson to beat the Montreal Expos, 2-1, on Friday night.

And, finally, he hit No. 48 off Stan Bahnsen – establishing an all-time record for a third baseman to beat the Expos, 6-4, in the 11th inning Saturday night and clinch the division title for the Phillies.

He had hit home runs before. Lots of them. But this was a different Mike Schmidt than the one who heard all those Veterans Stadium jeers earlier in his career. This was a Mike Schmidt who had learned how to concentrate, and how to perform to the utmost of his exceptional ability under extreme pressure.

"It's beautiful to see that type of confidence that comes from maturing," McCarver said.

The 1980 Mike Schmidt is a guy who, even ' when he fails to drive home a big run, can keep a positive outlook.

In Saturday's game in Montreal, Mike looked at a third strike from Steve Rogers with the bases loaded in the fifth and the Phillies trailing, 2-1. Walking back to he dugout, he passed the next batter, Greg Luzinski.

"Pick me up," Schmidt told him. "The comment he made to Bull, those are the little things that Schmitty would never have even thought about in past years," McCarver said.

Let's forget the past. Schmidt has become a steadying influence on this Phillies ball club, a calm in the center of what has been a season-long storm. He is the man who kept his head while, it often seemed, all around him were losing theirs.

Mike Schmidt doesn't have temper tantrums over negative newspaper stories, doesn't go into a blue funk when the Veterans Stadium fans boo him for popping up with a runner on third and one out, which he did in last week's 15-inning heart-pounder against the Cubs.

He just roots like hell for somebody to pick him up.

"I'll tell you what," he said the day after the Phillies pulled out that marathon game with a dramatic, two-out rally, "that was a special moment for me. Just going back to the bench and watching (Garry) Maddox walk up to home plate... I wasn't verbally yelling at him or screaming at him or anything like that. I wasn't showing a great deal of emotion, but I guarantee you that inside I was concentrating as hard as I could concentrate. I could sort of see the look in Garry's eyes that he knew this was an important at-bat, a big hit to get, and when he got it (to tie the game) you just sort of feel like that's what it takes to win divisions. The time when people least think you're going to pull out a ballgame, you do it."

Ordinarily, Schmidt is anything but a demonstrative player. He is the personification of the calm, cool professional athlete. And yet there were times in the Phillies' late run to the wire that some of his inner fire showed through.

In the home loss to the Expos on the next to last Sunday of the season he kicked at the dirt in obvious frustration when his two-out smash to left center with the potential tying run on first base bounced over the fence for a ground-rule double, forcing the runner to stop at third.

In that pivotal 15-inning struggle that started the Phillies' winning surge the following night, Mike showed his emotions twice - when he hit the ball sharply to short for a bases-loaded double play in the fifth, and again when he hit that pop fly with the tying run on third and one out in the 15th.

Watching him that night, and on the nights and days that followed, you knew how badly Schmidt wanted to win.

"It's probably the most emotional time of my career," he said as the Phillies prepared to head for their weekend showdown in Montreal. "Emotions are probably running higher for me personally and probably for almost all the guys on our team than at any time in their careers with the possible exception of Pete (Rose), who's had many emotional, team-oriented times in his career as well as individual....

"I don't think this is our Last Hurrah or anything like that. Speaking for myself, I feel simply that it's a time in my career where I can have a great year and be part of a winning cause. Who knows what's going to happen over the winter or the rest of your life? You may never get an opportunity like this again and you've got to make the most of it while you've got it.

"There are people all over wondering if we are trying to make the most of it," Schmidt said that day. "But each individual has to deal with that, I think."

Schmidt has dealt with it beautifully, never losing sight of his objective, his concentration seldom wavering.

Now, when he smashes a hard-hit ball at somebody, he doesn't let it upset him. Now, when he strikes out with men on base, he doesn't carry the disappointment, the frustration to the plate with him the next time.

Failure, he has learned, is part of being a baseball player. A very large part. "(No matter how good a hitter you are) you're still going to fail more times than you succeed in this game," he is fond of saying.

The statement may seem obvious. Of course, even a.300 hitter "fails" 70 percent of the time. But learning to accept the obvious, and to live with it can make a tremendous difference. That, too, is part of maturing.

One failure, though, Mike Schmidt would have had trouble accepting this year. Had the Expos won that final series in Montreal, the disappointment would have been severe.

"You know," he said before that climactic series began, "if I don't get a hit the rest of the year I'll still have good numbers (in home runs, runs batted in and runs scored), but man, I'll tell you what, I'm such a believer in it's what I do tonight that counts.

"It could be the greatest season I ever had or it could be a mediocre season as far as I'm concerned. The numbers will be there (no matter what), but it's the asterisk by the numbers that means they were in the playoffs and the World Series, it's the possible ring on my finger that's going to make it all worthwhile."

That's the 1980 Mike Schmidt talking.

That's the most valuable player in the National League, a man who dominated the power game as dramatically and convincingly as Steve Carlton dominated the pitching game.

In this, the year of the Phillies, they stand out above all the rest.

Meet George Brett, the summer’s star

By Mike McKenzie, Kansas City Times

By the final week of the season, the relentless renditions of the .400 Nightly News had worn thin for George Brett. During a weekend in Minnesota, Brett, for the first time, refused to grant interviews, pre-or post-game.

Brett had endured a 4-for-23 slump, skidding from .401 to ..385 in a week's foundering. And what suddenly occurred to him, during a discussion with a reporter, he said, was that he was set up to become a failure in one of the most marvelous hitting seasons known to modern baseball.

"Regardless of what I hit, I felt people were going to say, 'He failed in what he set out to do,'" Brett said. "Well, I didn't set out to hit .400. I was blowing the season for myself, being very impatient, swinging at a lot of bad pitches, Tying too hard.

"I just want this game to be fun. This should be a year I enjoy more than any other in my life, but I was getting to be a basket case. I snapped."

George Brett, All-Star third baseman, was tracked the past two months by every major newspaper, magazine, and radio and TV network while he was busy chasing hitting standards of Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Walt Dropo, et. al.

Incredibly, although Brett missed over a month of the season with injury, he finished the season in the top 10 of seven offensive categories, and led the American League in average, on-base percentage, and slugging.

Such feats brought even the President into Brett's limelight.

On a recent stumping tour of nearby Independence, Mo., President Carter matched grins with Brett while exchanging bumper stickers. The one Carter received said, "Brett for President." Carter later reported he made a deal with Brett "that he won't run this year."

The Brett sticker originated from Kansas City (Kan.) Community College to raise scholarship funds. To date, officials there say they have sold enough at $1.50 to offer two scholarships a year for 15 years.

After the first month of the season, Brett was batting .247. Following a seven-day layoff with a bruised heel, he moved to .337 before injuring a foot on a slide into second base attempting to steal.

He sat out a month. He began playing again after yielding his spot in the All-Star lineup.

During a 30-game streak stalking DiMaggio's magical 56 straight, Brett's average fluctuated from .373 to a peak .407.

Many believe Brett already has become a hitter nonparallel. Orioles manager Earl Weaver had Brett walked intentionally with runners at first and second in the ninth inning of a tie game. Amos Otis then walked to force in the winning run, and Weaver said, "I'd be a fool saying I won't let Brett beat me, then let him. It's the only way I could have felt worse about the loss."

Next night, Brett had the winning RBI against the Orioles, then three consecutive nights against the Toronto Blue Jays. With Brett out of the lineup, the Royals were 22-22.

An important breakthrough in Brett's hitting style came a year ago in May. He was hitting .240, and not using off-season surgery on his right thumb as an excuse, though he wore a clumsy protective device on it several months.

It's a time in which Brett became self-reliant. He gives credit to batting coach Charlie Lau (now with the Yankees) for teaching him patience and hitting to all fields. Brett never had hit .300, minor leagues or major, until Lau's tutelage. Since 1975, Brett is a .310 hitter and climbing.

After the Royals fired Lau in 1978, Brett struggled. "I had been babied," he said. "We talked after every at-bat about what was good and what wasn't. And I took extra hitting practice every day. When he left, I was like a frustrated kid. I didn't know how to apply myself."

Then one day, then-manager Whitey Herzog noticed Brett wasn't touching the bat to his shoulder and pulling it back at the last split-second, a trait Brett had developed for timing, "I thought, 'You dummy, you forgot!'" said Brett. "All of a sudden, boom, boom, boom. Since then, whenever I miss a pitch I saw, I laugh and think, 'Ha, you've got another strike left and you're going to hit the ball hard.'

"The way I feel now, I expect two hits a game no matter who's pitching. I forget about bad games. I never had that kind of confidence before."

Catcher Darrell Porter, also an All-Star, offered this insight about Brett's hitting: “It's hard to bat behind George, because if he does good it's hard to top his act. And if he doesn't get a hit, you think, 'Good grief, what's this pitcher got? I've got to go up there next?'”

Brett said he was chilled and overwhelmed by a standing ovation after the double at home last month that pushed his average over .400 the first time. "Now I know what it would have been like to hit the three homers in the playoff game at home." He homered three times off Catfish Hunter of the Yankees in the fifth game of the 1978 playoffs, and was booed each time by Yankee fans.

This season, Yankee fans, Cleveland fans, Anaheim fans, all fans, offered standing ovations. At home, he was summoned out of the dugout so many times he was embarrassed by it.

Headliines followed Brett all year, and not just for hitting. He has agreed to a contract extension which will pay him $250,000 this year and next on top of his current $380,000 salary, then $1 million a year from 1982-86, give or take a bag of peanuts.

This has created a stir among some teammates who have requested contract renegotiations and received a cold shoulder from management. "Nobody holds it personal against George," said Frank White, one of the restless. "He deserves it. But it affects us all."

Another spotlight hit Brett in Detroit when he rushed Tiger pitcher Milt Wilcox after two tight pitches. Nothing came of it.

Injuries have had Brett suffering from what he calls in Yiddish shpilkes disease. "Ants in the pants," he explained.

During the first week out, he pinch-hit twice, and once fell flat on his lace running to first. You could feel the stadium tremble.

After three injury-free seasons, Brett has been sidelined with ailments in the shoulder, elbow, thumb, knee, heel, foot and hand in the last four years. He said he always was getting hurt as a youth, if not at the field, at the beach near his home in El Segundo, Calif.

"Some say I have no regard for my body," he said. "But the only way the game is fun is going beserk."

Six rookies from farm give Phils fresh life

By Allen Lewis, Special to the Inquirer

Until the era of free agency, the life blood of any successful major league team was always its farm system.. The clubs that scouted well, spent bonus money wisely and developed the minor league talent they signed ended up winning pennants, or at least being serious contenders. At that stage, a little bit of luck was helpful, too.

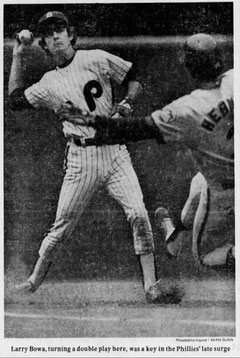

The Phillies, who spun their wheels for so long without really accomplishing very much after the Whiz Kids won the National League flag in 1950, won division titles in 1976, 1977 and 1978 largely because of the players who had come out of their farm system. All-stars like third baseman Mike Schmidt, left fielder Greg Luzinski, shortstop Larry Bowa and catcher Bob Boone formed the nucleus of those championship clubs. Pitchers from their system like Larry Christenson, Dick Ruthven, Randy Lerch and Warren Brusstar also played a part as did, of course, the others who came in trades, players such as pitchers Steve Carlton, Tug McGraw, Ron Reed and Jim Lonborg; outfielders Garry Maddox and Bake McBride, and second basemen Dave Cash and Ted Sizemore.

One or two good crops is enough to convert an also-ran team into a contender, but the secret of the ultra-successful clubs is to keep them coming year after year. That's the way the Los Angeles Dodgers, the Cincinnati Reds, The New York Yankees, Baltimore Orioles, Kansas City Royals and the Phillies have done it in the 1970s.

When the Phillies, after winning three division titles in succession and being favored to win a fourth, fell down so badly in 1979, part of the blame was put on complacency, and owner Ruly Carpenter, general manager Paul Owens and manager Dallas Green decided there would have to be some changes to correct any attitude deficiency. And yet, they didn't feel there was any necessity to trade off the established stars. The tenor of their joint decision was: Let's give them one more shot and change some of the members of the supporting cast.

It's not an exaggeration to say that the Phillies could not have won their fourth NL East championship in five years this season without the significant contributions made by those new faces, especially those of the rookies.

Few clubs in either major league can match the 1980 rookie crop of the Phillies. Outfielders Lonnie Smith and George Vukovich, catcher Keith Moreland, infielder Luis Aguayo and pitchers Bob Walk and Marty Bystom have all done outstanding jobs. So have second-year farm products Dickie Noles and Kevin Saucier in the bullpen, and Ramon Aviles in the infield. Without them, the Phils might well have finished third.

A lot of the credit for their contributions must go to Green. As the club's farm director when all these players were signed as free agents, he had a special regard for the youngsters, and none knew the capabilities of them as well as he did. When trades were discussed involving Smith, the manager was vehemently opposed. When there were discussions about trading or releasing veterans and using these youngsters on the parent club now, Green's voice was the loudest in support of going with the home-grown products. It's similar to the situation Owens found himself in some years before, when he was the farm director and John Quinn was the general manager and Gene Mauch the manager.

The only difference is that Owens lost most of his arguments in support of his farm club products, and players like pitchers Curt Simmons, Ferguson Jenkins and Don Cardwell, and outfielder Adolfo Phillips went elsewhere.

No non-pitching rookie in either major league has contributed to a pennant contender what Smith has to the Phillies this season. When Greg Luzinski was sidelined for a considerable spell because of an ailing knee that required surgery, Smith stepped right in and showed the kind of ability Green always maintained he had, although he's a completely different type of player than the man he replaced.

The Bull is a slugger, Smith a slinger. Smith just seems to sling the bat at the ball and hit a line drive, a ground ball or even a little looper over the infield, but he finds holes consistently. Once on base, he has been a constant threat to run and has made good on a high percentage of his steal attempts, giving the Phillies a type of leadoff man they haven't had since Richie Ashburn left after the 1959 season.

For much of the season, Smith has had the highest batting average in the league, although his lack of times at bat has kept him from being listed with the top hitters.

On defense, Smith has deficiencies, but his blazing speed has many times enabled him to overcome a mistake in judgment, and his hard work on his fielding has improved his glove work over a year ago.

Moreland appears to be the Phillies' regular catcher of the future. The rugged, blond Texan, a third baseman and football defensive back at the University of Texas, developed rapidly after being shifted to catching following the 1976 season. He was the American Association's All-Star catcher last year, when he hit .302 with 20 home runs and 109 runs batted in for Oklahoma City.

After being brought up to the Phillies last September, he showed major league ability when he caught the last two weeks of the season in place of Boone, who required surgery for a knee injury. While he draws special praise for his hitting ability, he has done well receiving and throwing, and has adjusted well to his part-time role.

Vukovich was ticketed for Oklahoma City this year after batting .293 and knocking in 88 runs for the Phillies' Reading farm club in the Eastern League last season. In spring training, however, he sprayed so many line drives and showed so much major league ability in the outfield that Green felt compelled to keep him on the squad even though, like veteran outfield spares Del Unser and Greg Gross, he was a lefthanded hitter.

Aguayo, 21, a Puerto Rican who was called the most improved player on his team last year by Oklahoma City manager Lee Elia, now the Phillies third-base coach, also had an outstanding spring training and earned a spot on the, roster.

With all that the other rookies have done, there's no doubt the Phillies never could have threatened for the division title without the pitching of Bob Walk and Marty Bystrom.

Walk was brought up from Oklahoma City after winning five of his first six decisions in his first weeks in Triple-A ball with Oklahoma City. He moved into the starting rotation with the Phillies when Larry Christenson and Nino Espinosa were sidelined with physical problems, overcame some physical problems and became the winningest rookie pitcher in the league when he defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers on Sept. 4 for his 10th win.

Three days after that game, Bystrom made his major league debut, pitching a perfect inning in relief against the Dodgers. The righthander had been Green's choice prior to spring training to make the club, but a severe groin pull wiped out his chances then. He went to Oklahoma City where he finally began to pitch in July, and joined the Phils in September.

All Bystrom did in his first start was pitch a shutout, starting a string of five wins and 20 scoreless innings.

Leading off for ABC – Keith Jackson

By Lee Winfrey, Inquirer Staff Writer

Unlike some sportscasters, Keith Jackson is a modest man.

"I think most sports announcers are overrated," he said in an interview here. "Generally an announcer has little to do with the overall product."

Whatever he thinks of his worth, Jackson has drawn another choice assignment on television tonight. He and Don Drysdale and Howard Cosell will be the three men in the booth when the Phillies open the National League championship playoffs at 8 p.m. on ABC (Channel 6).

Tomorrow afternoon at 2:30, Al Michaels, Billy Martin, and Jim Palmer will be the voices as ABC covers the opening game of the American League playoffs in Kansas City, where the Royals will be at home against the New York Yankees.

This will be the fifth straight year of post-season baseball work for Jackson, who also specializes in college football. He helped cover the playoffs for ABC in 1976 and 1978 and the World Series in 1977 and 1979. NBC (Channel 3) will cover the World Series this year, beginning next Tuesday, Oct. 14.

ABC's baseball coverage has improved considerably since 1976, as Jackson readily admits. "We've become more simplistic," he said. "We've outgrown the need to use every possible technological device. We had a tendency to overproduce, and that becomes cluttered."

When ABC resumed covering baseball in 1976 after more than a decade away from the diamond, its early efforts drew more jeers than cheers. After several announcers, led by Bob Prince and Warner Wolf, were sent to the showers, Jackson was called in to relieve.

"The package was not doing well," Jackson recalled. "I'm in Dallas to do the Texas-Oklahoma football game and I get this call: 'Will you go to Kansas City and join Howard and do the Kansas City-New York baseball playoffs?'

"When I walked into the booth and sat down that Saturday night," Jackson said, "that was my first baseball game in 11 years and I was Captain Pucker."

But he did so well, then and now, that ABC would no more think of covering post-season baseball without Jackson than Bowie Kuhn would consider putting on a topcoat to attend the World Series.

Jackson is a man living out his childhood ambition. As a boy growing up on a farm in Carrollton, Ga., he said, "I'd sit on the tractor and call (imaginary) ball games."

He took a couple of detours on his way to a real microphone, though, first a four-year tour of duty in the Marine Corps and then at Washington State University where he originally intended to study to become a policeman. He got back on track when he started announcing on the campus radio station.

Jackson worked more than a decade for a TV station in Seattle before joining ABC in 1964. "I've had two jobs in 28 years," he said. "One wife."

Jackson's wife means a lot to him. Among other things, she is responsible for his new beard.

"We have a home in British Columbia," he said. "This summer I had a month off and I just let it grow. My wife liked it and that pretty much took care of the decision. Besides, it covers up my double chin.

"I tell people," he smiled, "that I grew it because I got tired of being mistaken for Jim McKay. I guess it's because he and I both have round faces."

Apparently a lot of fans have trouble keeping announcers names and faces straight. "I was leaving the stadium today," Jackson said, "and a guy beat on the window and wanted to know if Curt Gowdy was in the car."

The easy-going Jackson seldom draws hostility. Although, he said, "One time a fella who'd had too much to drink, whose team had lost on a fluke play, took a swing at me. I hit him in the mouth and got in the car and left."

Jackson remembers only once that he was at a loss for words on the air, and that incident came early last year after Matt Franklin of Philadelphia (now Saad Muhammad) beat Marvin Johnson for the light-heavyweight boxing championship.

"I think it was one of the all-time classic fights," said Jackson. "After the fight, I was talking to both fighters on camera and I asked Franklin if he would like to see a slow-motion replay. And he said, 'No sir. I have too much respect for him (Johnson).

Well, I stumbled around and around and I didn't know what to say. It was the only time I was ever floored, not knowing what to say."

Tonight, 11 cameras will join Jackson at Veterans Stadium. Dennis Lewin will produce the telecast, with Joe Aceti as the director.

Lewin agrees with Jackson that ABC's baseball coverage has improved. "We stunk in 1976," Lewin said.

"That was an Olympic year and a presidential election year," the producer recalled. "From an engineering standpoint, it was a busy year for ABC. Not all the eggs were put into the baseball basket."

ABC, widely praised for its Olympics and "Monday Night Football" work, probably went into baseball a little overconfident, Lewin said. "We attempted to do things too fast, too soon, trying to personalize the game before we got the basic rudiments of coverage down."

NBC had televised the World Series for 30 consecutive years before ABC covered its first one in 1977. Lewin said he thought it took ABC more than two years to achieve parity with NBC in baseball coverage.

"Now our producers and directors are far more aware and better prepared," said Lewin. "Our camera men can anticipate situations that they couldn't in 1976.

"I like to think that visually we're at least on a par with NBC," Lewin said. "I think that NBC, philosophically, has gotten into replaying from every camera they have just to prove to the viewer that they have it. Maybe I underproduce, but I think replays should show quality.

"I think we're ahead of them in the booth," Lewin continued. "Their approach is more a couple of old ballplayers coming into your living room and chatting about the game and throwing in a couple of anecdotes for kicks. Our approach is to personalize as much as we can.

"I think the viewer of today is a far more sophisticated viewer than 10 years ago," Lewin concluded. "I think NBC's approach is that of 10 years ago."

This month – first with ABC in the playoffs, then with NBC at the Series – you'll have another chance to compare and contrast the coverage of the two networks. They keep trying to do better all the time, and hope fervently that you will think so.

The Schedule

National League

Tonight – Houston vs. Phillies at Veterans Stadium, 8:15 p.m. (TV-Chs. 6, 17; Radio-KYW-1060).

Tomorrow – Houston vs. Phillies at the Vet, 8:15 p.m. (TV-Chs. 17, 6; Radio-KYW-1060).

Friday – Phillies at Houston, 3 p.m. (TV-Chs. 6, 17; Radio-KYW-1060).

Saturday – Phillies at Houston, if necessary, 4:15 p.m. (TV-Chs. 6, 17; Radio-KYW-1060).

Sunday – Phillies at Houston, if necessary, 8 p.m. (TV-Chs. 6, 17; Radio-KYW-1060).

American League

Tomorrow – New York at Kansas City, 3 p.m. (TV-Ch.6;Radio-WCAU-1210).

Thursday – New York at Kansas City, 8:15 p.m. (TV-Ch. 6; Radio-WCAU-1210).

Friday – Kansas City at New York, 8:15 p.m. (TV-Ch. 6; Radio-WCAU-1210, joined in progress after 76ers game)

Saturday – Kansas City at New York, 8:15 p.m., if necessary (TV-Ch. 6; Radio-WCAU-1210).

Sunday – Kansas City at New York, 4 p.m., if necessary (TV-Ch. 6; Radio-WCAU-1210).